Bob Stein in conversation with Dan Visel

From Mao to Microsoft, a conversation on the unrecorded history of online publishing.

In 2004, Bob Stein founded the Institute for the Future of the Book, with the goal of finding new models for publishing as it moved from the page to the screen, from the enclosed world of the individual reader to the networked one of the Internet. While innovative for its own time, the Institute’s mission built on Stein’s decades of experience exploring the frontiers of electronic publishing, whether with Atari, the Criterion Collection, or Voyager. Long before the popularization of the Internet, the tools that Stein developed for publishing with floppy disks, CD-ROMs, and LaserDiscs laid the groundwork for dramatic shifts in how we interact with (formerly) printed media. Much of his work proposed hybrid formats, combining the referential nature of books with the visual appeal of films, using computers to turn texts into what Stein was already calling, in the mid-’80s, “user-driven media.” Today these hybrids seem natural, but the history of publishing and technology prior to the Web, which has largely gone unrecorded, suggests that the evolution of the medium was not prescribed, but rather spurred by the experiments of Stein and his cohorts. The Public School New York invited Stein to discuss his work with Dan Visel, a researcher at the Institute for the Future of the Book. Their conversation spans Stein’s entire career, charting a prehistory of online publishing that continues to be a source of inspiration and innovation.

Illustrations on the following pages: conceptual drawings for the Intelligent Encyclopedia project, commissioned by Atari, 1982.

Bob Stein: I went to Columbia. I was a founding member of Students for a Democratic Society there in 1966. I went from Columbia to Harvard, then out to the University of Washington, then dropped out after a week to become a full-time organizer. It’s hard to imagine what it was like during that period, when anything having to do with school or career took a backseat to everything going on in the streets.

I ended up in Seattle. Since I was educated, I ended up working on the local left-wing newspaper, called The Sabot—short for “Sabotage.” Six years later, I had become a Marxist and a Maoist and was working closely with the Revolutionary Communist Party. I started a bookstore in Seattle and then one in New York: Revolution Books on Twenty-sixth Street. So my background in publishing was actually in distribution, in bookselling, not so much in writing or in editorial.

DV: Did you see that as a means to an end?

BS: Even though I went to all the fancy schools, I never considered myself a writer, nor an intellectual. I came out of a merchant background, so bookselling was easy for me.

After doing serious left-wing political publishing—Banner Press, RCP Press—for a number of years, I stopped doing political work in 1980. I moved to Los Angeles; I was working nights as a waiter, and I spent all day, every day, in the library. I was really excited about the new interactive video technology coming out of MIT and began thinking about publishing on interactive LaserDiscs.

DV: Around that time, you started developing an electronic encyclopedia. How did that concept come into being?

BS: It came from an article by Ralph Gomory, the chief scientist at IBM. He talked about how you could put the entire Encyclopædia Britannica onto a single LaserDisc. So I wanted to put Random House’s encyclopedia onto a LaserDisc. It was that simple. What I didn’t understand was that he meant the number of bits in the text of the Encyclopædia Britannica could fit onto a LaserDisc. And in fact, if you just took pictures of the pages, they would be illegible. But none of us understood that at the time.

DV: And there was no way to read back whatever you had once it was on the LaserDisc.

Alan Kay, conceptual drawing for the Dynabook, 1967.

BS: Right, and in fact nobody ever did put an encyclopedia on a LaserDisc. But it was a good conversation starter. I was invited to Britannica, and they wanted me to show them what LaserDiscs were all about. You have to understand, I knew nothing. I got paid, basically, to spend a year going around the country with their imprimatur, going to every lab I could, saying, “Show me what you’ve got.” I wrote a 120-page paper on the Encyclopædia Britannica, which suggests that the encyclopedia of the future would likely be a joint venture of Xerox, Lucasfilm, and Britannica.DV: Xerox basically invented all of the parts of the computer that we know and love: the mouse, the windowed interface.

BS: Alan Kay, who had been one of the chief scientists at Xerox and had moved to Atari by that time, came up with the idea for the personal computer.1 In 1967, he proposed the Dynabook, which was something like the iPad. He’s been chasing this dream all his life. I desperately wanted to talk to Alan. So one day I just got on the phone and called him. He answered the phone and said, “Come on up here and talk to me.” I went, and—this is not an exaggeration—he sat and read the entire 120-page paper while sitting at his desk. And he said, “This is great, why don’t you come and work with me?” So I did.

DV: What did you do at Atari?

BS: Alan brought all these kids, mostly from the MIT Media Lab, out to Atari, which was owned by Warner Bros., which did not have a clue. The goal was to build a consortium that would create the intelligent encyclopedia of the future. Alan was allowed to spend as much money as he wanted, literally any amount of money—on anything except hardware. So he had all these computer scientists there without any machines. Which meant a lot of meetings.

DV: There is a series of pictures from this time conceptualizing the encyclopedia and how it would be used, showing a bunch of people using a device that looks a lot like an iPhone. Is there any other record of the project?

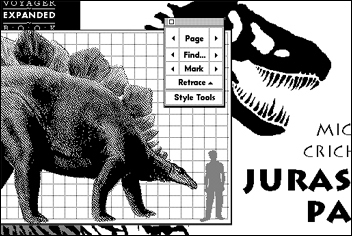

Citizen Kane, Criterion Collection LaserDisc, 1984. Douglas Adams, The Complete Hitch Hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, Voyager Expanded Book, 1992.

BS: We had a zillion meetings with people, but nothing ever came of it. There were some papers written, but very few. Every other week, I would fly to New York and go to the thirtieth floor of 75 Rock to meet with the Warner Bros. executives. I would try to explain to them this amazing company they owned in California. They totally didn’t get it. Finally, I hooked up with Stanley Cornyn, from the records division, who had been given the job of deciding what Warner would do with the compact disc. There was going to be an interactive version, and he was supposed to make titles for it. He asked me to come up with some ideas; I developed ten projects, and of course nobody wanted to fund these. Warner wasn’t going to make a series of CD-ROMs. Nobody was in 1984.DV: Did it seem at this point like LaserDiscs were about to take off?

BS: No. VHS was exploding. It was like being in the CD-ROM business when the Web was exploding. I was at a meeting one day with the president of RKO Home Video, and I said to him, “So, what’s the chance you would sell me the rights to Citizen Kane and King Kong for LaserDisc?” He said, “Well, they’re not worth anything to us. Of course I’ll sell them to you.” So I bought the rights to two of the most famous movies ever made. I had a choice: I could make stuff for the Apple II, but aesthetically I just couldn’t stomach it. (That was the age of pea-green text on a black screen.) So I went with LaserDiscs.

DV: And you started the Criterion Collection?

BS: Yes. It was just of one of those things where—I mean, I like movies, but I’m not a movie buff. I just knew I could do something interesting with them. You have to understand how much of this stuff is accidental. I knew the guy who was the curator of films at the LA County Museum of Art, and I brought him to New York to oversee color correction. He’s telling us all these amazing stories, particularly about King Kong, because it’s his favorite film. Someone said, “Gee, we’ve got this extra sound track on the LaserDisc, why don’t you tell these stories?” He was horrified at the idea, but we promised we’d get him superstoned if he did, and he gave this amazing discussion about the making of King Kong, which we released as the second sound track.

DV: And that was the start of what became DVD extras. At what point did people see that Criterion was something new and exciting?

BS: Oh, the first day. We had people driving to our home, where our offices were, by the second day, and begging for copies. It was Los Angeles, it was the film industry—and finally someone had done something serious with film. Film was suddenly being treated in a published form, like literature. But this still wasn’t mainstream. Citizen Kane was three discs and cost $125. It cost us $40 to manufacture. The most LaserDiscs we ever sold was about twenty thousand copies of Blade Runner. To us, the LaserDiscs were mainly cash flow: We had millions of dollars running through the company, which let us pretend we had enough money to do more experimental stuff.

DV: Did Voyager, the CD-ROM publisher, spring from Criterion?

BS: Well, I bought the rights to Poetry in Motion, a 1982 documentary by Ron Mann, a Canadian filmmaker. He had twenty-four fantastic North American poets, mostly Beats, many of whom used music, performing their work: Allen Ginsberg doing a rock ’n’ roll song, Amiri Baraka doing a beautiful poem with a jazz band behind him. It was a fantastic film. I published it on VHS to start, and I called that company Voyager. And then Voyager ended up buying Criterion.

DV: Had the idea of the book taken a backseat?

BS: The book was always fundamental to me. One of the things I really liked was that the original logo for Criterion, which we designed in 1984, was a book turning into a disc. It was central. When I was writing the paper for Britannica, I felt like I had to relate the idea of interactive media to books, and I was really wrestling with the question “What is a book?” What’s essential about a book? What happens when you move that essence into some other medium? And I just woke up one day and realized that if I thought about a book not in terms of its physical properties—ink on paper—but in terms of the way it’s used, that a book was the one medium where the user was in control of the sequence and the pace at which they accessed the material. I started calling books “user-driven media,” in contrast to movies, television, and radio, which were producer-driven. You were in control of a book, but with these other media you weren’t; you just sat in a chair and they happened to you. I realized that once microprocessors got into the mix, what we considered producer-driven was going to be transformed into something user-driven. And that, of course, is what you have today, whether it’s TiVo or the DVD.

DV: Could you talk about the first wave of e-books?

BS: We had a friend named Florian Brody, who worked for the National Library of Austria. Florian was at our offices in California the day in 1990 when Apple sent us the first prototype of the PowerBook. It was a little thing. He grabbed it out of my hand and disappeared. Half an hour later he comes back, and he’s put the first ten pages of The Sheltering Sky into a HyperCard stack.2 Just the text on the screen, and you click on it and the page is there. We’d been talking about electronic books for years, but we assumed it was in the seriously long-term future. When Florian showed us this we looked at each other and said, “Oh, it’s here, now.” This is probably late 1990, early 1991.

Michael Crichton, Jurassic Park, Voyager Expanded Book, 1992.

DV: HyperCard had come out in 1989.BS: Yes, but the only device that would run it at that time was the desktop.

DV: And it just didn’t occur to you to do it on a desktop? You needed a portable computer?

BS: It didn’t seem right. The intimacy always seemed to me like part of the equation. So Florian did that, and we got a grant from somewhere to do the first books. The first three were the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy trilogy; Jurassic Park, before it came out in paperback; and Martin Gardner’s Annotated Alice. We had programmers working on the software; every morning I’d come in, and they would have put all kinds of bells and whistles on the book. It would take us the entire morning to go through each one and figure out a way to hide them. Because I thought it was desperately important that it be just the text on the page.

DV: And those books actually got distributed.

BS: There were seventy-five titles in the end. They were on floppy disk. They just ran on a Mac until the very end. There are some fantastic stories of people’s use of them, but it was just too early. There was no distribution channel. We had to sell only books people had heard of because there was no way to browse them. But again, it was more a proof of concept than anything else.

DV: How did you go from books on floppy disk to CD-ROMs?

BS: The bandwidth curve went down. First we were doing little floppy disks that could control a LaserDisc player. Then in 1988 Apple came out with the first CD-ROM drive; I got it and literally ran to Robert Winter’s house the next day. Robert is a professor at UCLA who gave fantastic classes on classical music. He and I cobbled together a little demo of the CD-Companion, which was an attempt to do for music what Criterion had done for film. It took Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony and presented it with CD-quality audio, in a form where the average intelligent person could learn as much about that piece as they wanted.

DV: The music on the CD played, and Winter’s information about the section that was playing appeared on the screen; you could control it, move forward and back.

BS: Right. And it was early enough that we drove phenomenal sales of computers. Microsoft included copies with early versions of Windows. Schools all over the country—every music department—went out and bought multiple computers just to run this program. So that was what started us on CD-ROMs. And we actually made some money! The theme here is that every time new hardware came along, we were lucky enough to figure out what it was good for, and we did something with it. You couldn’t make much money off it, so big companies weren’t rushing in there. We paid our dues by doing the stuff that nobody else wanted to do. It’s exciting for me to realize that I published what in effect became the first DVDs, the first CD-ROMs, and the first electronic books. In all three media we were first.

DV: When did you start thinking about tool making?

BS: That gets back to HyperCard: What was cool about it was that people who couldn’t program could write HyperCard. Teachers, particularly high school teachers, glommed on to it big time. The first tool we made was the Voyager video stack, which let teachers make HyperCard stacks to control LaserDiscs. Then when we made the first CD-ROMs, teachers said the same thing, “This is fantastic. I want to do that.” So then we made the Voyager CD audio-stack tool kit, and then when we made the first electronic books. People said, “Wow. This is amazing, how do we this?” So we made the Expanded Books tool kit, which used HyperCard to allow people to create their own electronic books.

DV: It’s not as obvious as you might think to go from publishing to making tools to let other people publish. I’m not sure that most people would have done that.

Robert Winter, Mozart: String Quartet in C Major, Voyager CityRom, 1993.

Laurie Anderson, Puppet Motel, Voyager CityRom, 1995.

DV: Did Voyager end because the Internet came along?

BS: Voyager didn’t end because of the Internet. Voyager ended because—it’s a long story. Voyager had four partners: my ex-wife, me, and the two guys who owned Janus Films. We never took a vote and we did everything by consensus. This went on from 1985 until 1994, by which time the CD-ROMs were a big deal and everybody wanted to invest in our company. It was like a cook-off, you know: Who was going to win? We ended up taking money from the von Holtzbrincks, who now own Macmillan and Scientific American and a zillion other things. Now there were suddenly five partners, and money, and we didn’t know how to handle either the new partnership or the money. And then the Internet came along.

We got a call one day in 1995 from a guy at Morgan Stanley who said, “We’ve been studying the Internet, and we think that your company is best poised to become the really big winner of the Internet.” So I went away for six months to develop a plan: The core of the idea of Voyager on the Internet was 24/7, highly interactive broadcast. Laurie Anderson had agreed to do a live radio program every Sunday. Just before this happened, Paul Allen, Bill Gates’s partner in Microsoft, came along and offered to buy Voyager for thirty-five million dollars. Paul’s representative takes us to lunch and he says, “So we’re going to buy the company, and I just want you to know that it’s going to be different. You’re not going to run it quite like you do now, we’re going to run it like a real business.” And that was OK with me; it was my partners who didn’t like the idea. So we never made the deal.

This was October of 1996; DVDs were going to come out three months later. It was painfully obvious that the Criterion Collection on DVD was going to make millions and millions of dollars. This is a deal which any idiot would make.

DV: After the end of Voyager, you started Night Kitchen, a for-profit company; after Night Kitchen you started the Institute for the Future of the Book. Night Kitchen developed TK3, a piece of software, released in 2000, that enabled educators to create multimedia books; the Institute worked on Sophie, which allowed amateur programmers to create complex multimedia documents that utilized the Internet. (Sophie 2, a version of the original rewritten in Java, is still in development at the University of Southern California.)

BS: The zeitgeist that I’d been following, from Alan Kay at Xerox, to Alan Kay at Atari, to Apple, to Paul Allen's Interval Research Corporation think tank, had suddenly ended up at Microsoft, of all places. Microsoft was doing the coolest work in terms of the future of the book. And Dick Brass, who was running a research group there, saw this little demo of TK3 and said, “Oh my God, HyperCard done right,” and he threw all this money at us.

Microsoft was about to bring out its first tablet computer, but they had no way to produce anything for it. We finished TK3, went back to Microsoft for the money to take it to market, and they said to us, “We’ll give you as much money as you need, all you have to do is kill the Macintosh version of it.” And I was obstreperous enough to say, “Fuck you.” So it never came to market; it was orphaned.

Then, in a really sweet moment, the MacArthur Foundation called and said: “We loved the work you did at Voyager; how can we help you go back into publishing?” I said that I had no idea what it means to be a publisher right now, but if they gave me some money to start the Institute for the Future of the Book, I would think about it. And they gave me twice as much money as I asked for and no deliverables. That’s when I hired Ben Vershbow, Kim White, and you. That's been a really interesting collaboration because you were all in your late twenties, had grown up with the Internet to some extent, and it was the beginning of Web 2.0, which you were very comfortable with. We spent a year sitting around a table having discussions about what we could do with books, and what books were, and what they could evolve into.

DV: I’m curious why, for so long, you’ve felt it necessary to develop new tools for publishing, and thought that what we have isn’t good enough.

BS: I was telling a programmer today that if I have one regret it’s that I never learned to program. And I think that’s part of the reason why I’ve wanted these tools.

DV: I’d always thought it was your great virtue that you didn’t know how computers worked: You ask dumb questions, and people have to explain things from the beginning. That process of explanation can be really fruitful.

BS: Right, but with HyperCard, that was the first time I could make something for myself, and that’s what launched all of our creative work at Voyager. I wanted to go back to being able to do that. Now if I want to make something, I have to get a programmer to work with me; from my perspective, I needed tools so that I could do that first draft myself.

DV: Recently you’ve been involved with This Progress, the Tino Sehgal exhibition at the Guggenheim. When visitors enter that exhibition, they’re asked to explain to a small child what progress is. Then they have a series of discussions about those ideas, including, possibly, one with you. They end up questioning the notion of progress—even though they’re walking up the ramp of the Guggenheim. I’m curious what you’ve taken from that experience so far, especially since we tend to associate technology with progress.

BS: Here’s the scary thing: I’m in the oldest group. We meet visitors at the very top of the ramp. And most of the people in my group are pretty serious intellectuals, a lot of academics. We were sitting around talking, and we suddenly realized that all of us in this older group in one way or another have a dystopian view of the future, and that we really think things are headed in a scary direction.

The tools available for learning are exponentially more powerful than they were thirty years ago. A lot of the things I hoped for then are coming true. But I’m more concerned with how these tools are used and what they lead. When I went to Atari, all these young kids from MIT’s Media Lab were there. Every one of them absolutely had a vision of the future where things were just going to get better and better. There was no concept in their mind that real, fundamental change involves upheaval, and substantial upheaval. We’re not going to go gently into some utopian future.

This illustration, and previous: Conceptual drawings for the Intelligent Encyclopedia project, commissioned by Atari, 1982.