Jordan Crandall in conversation with Caleb Waldorf

A genealogy of Blast, a “system of editorial circulation” published between 1991 and 1995.

Caleb Waldorf: Blast seems to have emerged from the nascent digital culture of the early to mid-’90s, as well as from a direct engagement with the history of artist books and publications. How did the environment in New York at the time—where new network technologies were just arriving, but there was also a history of artists working with publications—contribute to the development of Blast?

Jordan Crandall: There was no digital culture then! Blast emerged at a moment when the dominant discussions around authorship were coming out of literary theory and deconstruction, and it was engaged with these questions about authorship and the nature of the text. In other words, the dynamics of textuality: How does a text format reality? What is an author? How do people inhabit a text and assume agency in relation to it, rather than passively receiving or consuming it? The text was becoming understood less in monolithic terms—as the singular creation of an author—and much more provisionally.

At the same time, there was an existing, thriving form within which some of these questions had been explored for the past three decades: artist books and publications like William Copley’s SMS portfolios, Aspen magazine, and various Fluxus projects—publications that were not bound magazines so much as collections of objects that oftentimes lacked a beginning or end.

CW: Had you explored this territory in the space of a magazine before?

JC: In the ’80s I had done a magazine called Splash, which covered art, fashion, popular culture, film, and music—a hybrid of Artforum and Interview. But it was a regular magazine, with advertising, conventional expectations, and certain demands that were imposed by the form. I felt that was very restrictive and frustrating; I wanted to engage with the magazine as an artistic medium. I wanted to subvert the expectations that came with a magazine of that nature.

CW: What is the formula of the magazine that you found frustrating? How were you trying to bring different logics, different ways of generating meaning, to bear on a form that has a conventional relationship between those who produce and consume it?

JC: You had to have a completely finished product, arranged in an unchanging sequence, with a fixed relation between institution, author, and reader. There was no space in which a reader could intervene, no way to experiment with other arrangements and assumptions. You had conventions that could not be interrogated, constraints that were in place that could not be questioned. You had content solely in the service of economy. Texts had a beginning and an end. Certain items had to come before other items. All those formal constraints and expectations that come with the magazine were elements that people would accept in an unquestioning way: Authors contribute articles, which are then edited and published in a precise order; the magazine is delivered to the reader, who leafs through it, then puts it on the coffee table and forgets about it. The magazine became this dead thing; it would never change, it was always the same static object. If you could unpack power relations in a film or photograph, why couldn’t you do it with the form of the magazine? I tried to work with that space of the conventional, bound magazine as much as possible design-wise, introducing some self-reflexivity, but there wasn’t that much to be done.

What I was really interested in was crafting an experience that the reader could somehow enter into and that could change over time. I wanted to create a possibility—I didn’t call it this at the time—for the content to be remixed. I wanted to transform the magazine into a site of investigation.

So in 1989 Splash folded, which was inevitable, given that I didn’t take it seriously as a business!

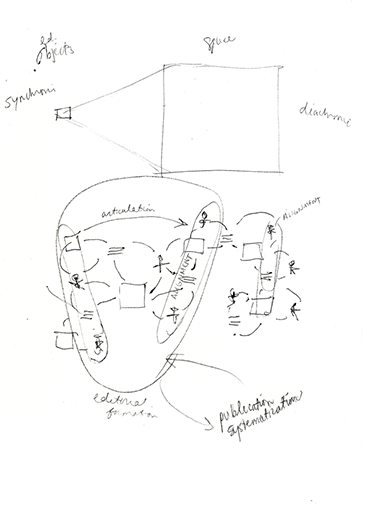

Diagram of Blast, 1994. Click image to enlarge.

Previous page: Blast 1, 1991. Above: Blast boxes.

CW: Blast 1 was published as a box containing discrete objects: unbound printed pages, photographs, an envelope of sheet silicate minerals, a computer disk. How did Blast take the model of a magazine like Aspen and adapt it for the present day?JC: Blast had to engage contemporary questions regarding textuality and digitization; at the time, these were oriented around nonlinear, interactive forms, primarily in literature. It also had to address new relations to materiality, to the object. Blast had to be a box because it had to have a dimensionality. It had to create a physical space, but a space that was mobile and fluid, a space into which people could insert things or out of which they could take them; a space that could incorporate new material over time. It also had to experiment with, or frustrate, conventions of attribution.

The Blast 1 boxes were completely unmarked. There were no labels or markings on them at all. The editorial items didn’t have titles or authors. D.A.P., the distributor, had to convey to booksellers what these boxes were and the bookstores had to convey to the customers what was inside them. I remember going to bookstores and seeing Blast and loving that there was just this unmarked box on the counter! Sometimes booksellers would improvise and put up an explanatory text. Some didn’t explain it at all. One day I went into a store in New York and saw a stack of the boxes. I asked an employee what they were, and, as it turned out, no one knew! I asked if they had sold any of the boxes, and they said yes, they had sold two! Another store had propped up a sign, handwritten in a schoolboy scrawl, that mistakenly said “Bomb.” Each box contained a form that asked for your contact information: After you purchased Blast, you would fill out the form, and then you’d have to fax it to the Blast office (basically a tiny basement in the East Village). We were fascinated by the fax. This was high-tech! After receiving your fax, I would write a letter to you. Certain dimensions of Blast would only come into view through this kind of conversation and participation.

CW: What kind of conversations did these faxes provoke?

JC: You could inquire about the projects: their history, their authors, their assumptions, their meaning, their connection to each other. But as in any good conversation, you get a sense of where your conversants are coming from first, and the nature of their interest, so you can help orient them.

CW: Blast wasn’t a journal or a magazine, then, but a sort of network?

JC: It was still positioned as a magazine or journal. I referred to it as a “vehicle” whenever I could, but sometimes it just confused people too much. We were definitely working with the paradigm of the magazine, while pushing it as far as possible at the time. But yes, that was the time—the early ’90s—when people were beginning to talk about networks, and right from the start, Blast was positioned as a network or system. The first sentence we used to describe Blast called it “a system of editorial circulation." The material in the box was intended as an instantiation of various flows, which could be altered and reintroduced into the system.

CW: What was the editorial composition of Blast? Who was the publisher?

JC: I established a nonprofit entity called the X-Art Foundation to act as the publisher. I was the director of X-Art and the editor of Blast. In the beginning it was basically just me, but by having a board of directors and an editorial council, by working with contributors, and by opening up these connections with readers, I was able to facilitate exchanges and help contour the project without authoring it. My identity was never listed anywhere; Blast was always just attributed to the X-Art Foundation. The questions I hoped readers would ask weren’t necessarily about who authored Blast or its contents but more along the lines of: How am I to deal with this box, or this particular object in this box, which comes to me without the usual coordinates, and which asks more questions than it answers? What is the context for this material? What is the structure or system that upholds it? How do I relate to it?

CW: Because you couldn’t Google it!

JC: Exactly! You can’t do things like that today.

Booklet produced for an X-Art Foundation benefit, 1993. Click on arrows to view excerpts.

JC: That’s part of what distinguished Blast from the magazines in a box of the ’60s and ’70s, but it wasn’t framed that way. It engaged in institutional critique via the institution of publishing, with the magazine as a vehicle—it was a metaphoric engagement. Some extrapolated from this, but for many Blast was just a curiosity. It didn’t directly engage those political economies of art, whether to perpetuate them or critique them.

CW: There's some friction between Blast’s participation in the art economy—inasmuch as it was sold in bookstores and exhibited in galleries—and its attempt to destabilize it. But since there were no authors, no editors, no branding, the project inherently resisted being sucked into dominant institutional and discursive systems.

JC: That’s an important way to see it; and yet, I didn’t really know what politics was at the time! I mean, I knew that artists did things to resist and inform, but I didn’t know what a political practice might entail. I certainly was not involved in any of the discussions around identity politics or political art at the time, though many Blast contributors, such as Simon Leung and Robert Atkins, were. Sometimes you know, in retrospect, that you were attuned to something, even if at the time you were unaware.

Screenshot of The Thing bulletin board system, 1991.

CW: Did the emergence of digital culture explain why, to some degree? Did it make these strands of thought palpable as a new form, or embody them?JC: My first encounter with what came to be known as “digital culture” happened after the first issue of Blast came out in 1991. I became involved with The Thing, a dial-up bulletin board system that facilitated discussions within New York City arts communities. The next year I began organizing discussion forums. There were all these issues related to digital experience and what “digital life” or “virtual bodies” were. At that time there was no real politics or criticality to these conversations. It was just so new! It was something we wanted to explore, to thrash about in. There was a profound fascination with this strange space and what people could do in it. You had to experience it first, because there was no discourse.

CW: So how did Blast change with the emergence of digital culture around The Thing?

JC: Around this time I got my first modem, which was given to me by Wolfgang Staehle, the artist who founded The Thing. I was instantly hooked. But it was slow going. People came aboard one by one. If there was a digital culture in New York City, it was like ten people. While organizing one of the early Thing forums I had to recruit people and show them how to get everything working: acquire a modem, install it, set it up. Wolfgang had to do this every day. You couldn’t explain it on the phone, because people had no idea. I remember going to the studio of Ben Kinmont, an artist who was going to participate in one of these forums. He had a modem, but had no idea what to do with it. I went over to his place and discovered, plopped on his desk, a 300-baud modem the size of a suitcase! It seemed primitive even then. It was so slow that the text appeared on the screen one letter at a time. Today it would seem absolutely Paleolithic.

People were just figuring out all the logistics. Blast 2 came out in 1992, and we included a hypertext program on a disk—a nonlinear, interactive, text-based encyclopedia, put together by Laura Trippi. At that time there was no HTML, but there was hypertext, its precursor; the people working with it were more in the realm of literary fiction than visual art. There was an interesting convergence of hypertext and many of the conversations that had been taking place around deconstruction. On the one hand there was hypertext experimentation and BBSs, and on the other there were text-based role-playing environments, multi-user domains (MUDs) and MOOs (MUDs, object oriented). We delved into these environments in the first three issues of Blast, and we eventually began to situate some of the magazine’s content online, which reoriented the function of the box. The fourth issue of Blast was published in 1994, and it contained a conduit to PMC-MOO—one of the original MOOs, run by the electronic journal Postmodern Culture—in which several Blast projects were situated. We presented the MOO space live in the gallery exhibitions we were beginning to do then, first at Sandra Gering Gallery in New York.

CW: Did the slowness of technological developments at the time allow for an opportunity to think deeply about these emergent digital forms in relation to Blast?

JC: Yes. These were essentially experiments in form. But there was no real coherent framework around it. There was time for Blast to move slowly, in tandem with technological developments, and engage them over a long duration. Now it’s clear that those early experiments were precursors to thinking about network textuality, before the Net existed. These conversations—about interactivity, virtual embodiment, and virtual identity—were already happening before the technology was in place. They were informed by experience, rooted in practices of nonlinear writing on BBSs, stand-alone programs, and role-playing sites like PMC-MOO, where there was even talk about the performativity of gender and identity in these emerging virtual environments. The technology wasn’t suddenly producing the thinking. Online spaces were part of the structure of Blast 3 and Blast 4, extensions of the boxes. The editorial listing in the boxes included items that could be found online.

Blast 3, 1993.

Blast 2 index, 1992. Click on image to enlarge.

CW: So Blast grew to contain things that weren’t in the boxes?

JC: Yes. It raised the question of whether the box was simply a container or a facilitator of some kind, and what function the index really served. We were interested in exploring the possibility of Blast being a mechanism that could open out into other spaces. If Blast was a system or a network to be engaged, then it also fluxed in and out of materiality. The box—the vehicle—then became a provisional container, an instantiation of a larger system and field of experiences. Blast 5 incorporated much more performative, time-based work, which led to the vehicle becoming a marker of activity, a visual emblem that indexed projects that happened elsewhere, an icon for the activities of Blast. We didn’t do a bookstore version of Blast 5—this wouldn’t have been possible, since it was a solid object with nothing inside it, with no resemblance to a magazine. It was only presented and distributed in galleries. The development of its form was an enormous undertaking, by the architectural firm of Sulan Kolatan and William Macdonald. A series of forms were modeled in a 3-D design program and output to objects in stereolithography, then cast in fiberglass. They were circulated as icons in a “Vehicle User’s Manual.” In a sense, Blast had always maintained the guise of a magazine. Now the masquerade was over. But that history informed how you were to see it. It certainly wasn’t just a sculpture.

CW: What motivated this transformation to the exhibition space?

JC: On the one hand Blast was set up to resist being a single, static object or experience. It could activate that the editorial space in other ways. The gallery was one venue where we thought the editorial space of Blast could be activated. The possibilities were everywhere around you: online, because the Web was flourishing at that point, and offline, in everyday spaces and situations. The goal was to integrate it into life, into everyday situations, where it could function as an orientation device, a mechanism of reflection and engagement. Since it has no economic pressures, there was always the sense that the project would go wherever it needs to. I vowed to never hold it back, never try to subject it to the demands of an institutional model. It was truly an experimental project, a trajectory of development that was unchecked in every way. One thing always led to the another. It was always very clear where it needed to go. When I finished one issue, I knew where the next one had to go.

CW: So why did the experiment end?

JC: It had nowhere to go. Blast 5 was the moment when the vehicle no longer had an interior. There was nowhere else to move from there, at least along the same line of development. I became interested in positioning Blast as a mobile agent of activity that could link up with other institutions and be a catalyst for various kind of discursive activities.

Previous page: Blast 4 rendering, 1993. Next page: Blast 5 vehicle, 1995.

JC: Yes. After Blast 5, the project adopted a mobile, flexible, multichannel format, temporarily affiliating itself, or “docking,” with various organizations and groups for periods of time. The magazine became a catalyst for other kinds of encounters, which no longer needed any particular material form. We docked with Eyebeam in New York City for a series of discussions which later were published in book called Interaction: Artistic Practice in the Network. We docked with Documenta X in 1997 for a series of discussions on issues of space and agency, then with INIVA in London in 2000. I also worked with Carlos Basualdo and Hans Ulrich Obrist in 1998 to develop the online presence of the curatorial organization VOTI—Blast was the host for all of its discussions. We did several Blast discussions over the next two years: The first was “The Museum of the 21st Century,” and the second was “Cultural Practice and War,” in 1999. Overall, the Blast project became increasingly critically and politically oriented—not inwardly, but toward the world at large.

CW: Do you see the legacy of Blast in any of today’s online projects that deal with the history of publishing and artist books?

JC: I think that one of the main concerns for such projects may be materiality, especially in the face of the digitization of so much of life and media—which seems to have a dematerializing function. This is illusory; life is material. How do you make something that is woven into the practice of daily life—not just something on a screen that you click through and then forget? Something that is more than information, content? The issue is one of substance, agency, and form. Blast was always invested in material things, even as it looked at how those things were reworked and reconstituted through information networks—systems of editorial circulation. The magazine was concerned with how those things function, how they speak, how they provide an interface for social relations; how communication is systematized, how form is instantiated. In a way, it was always looking at the agency that editorial objects possessed as real entities in the world. So if there is a legacy, it is an attention to the agency of things and the material manifestation of editorial relations—which are not to be taken for granted, or simply smoothed over, or rendered interoperable via the flat surfaces of computer displays. To do so is to resist, and interrogate, the demands of digital culture.