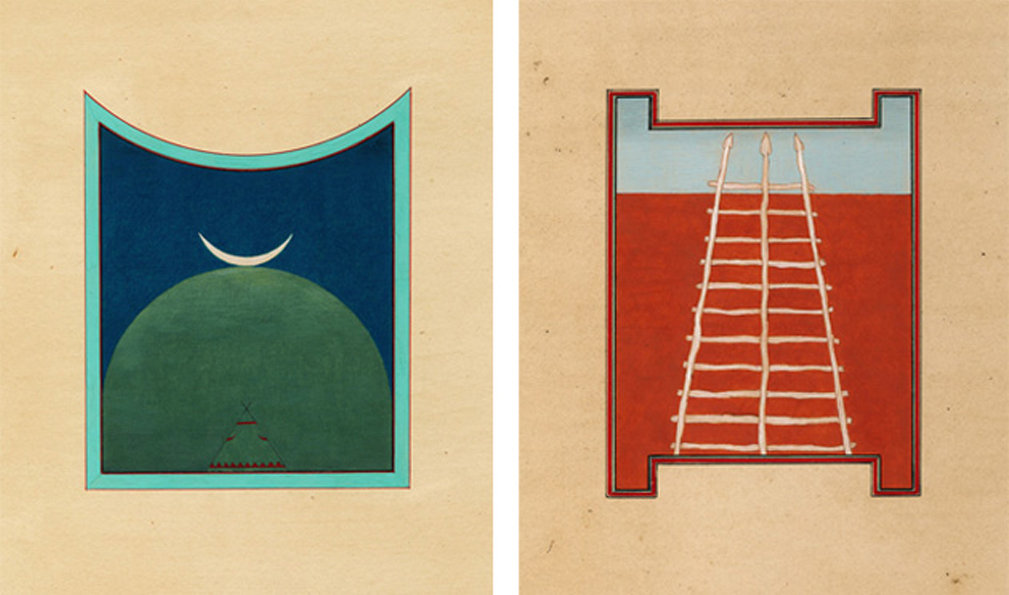

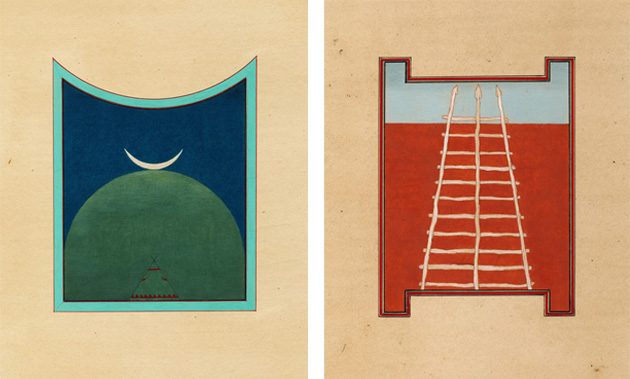

Murad Khan Mumtaz, Visitation, 2011 (left); Murad Khan Mumtaz, Kiva, 2011 (right). Courtesy of Tracy Williams, Ltd.

Murad Khan Mumtaz and Alyssa Phoebus, in their collaborative project “Origin, Departure,” for Triple Canopy’s thirteenth issue, Bad Actors, illustrated their experience of leaving America for Mumtaz’s native Pakistan by deconstructing and manipulating the materials facilitating their passage—their passports. For his recent series, “Return,” exhibited at Tracy Williams (January 12–February 11), Mumtaz revisits the Pakistani art of miniature painting. He speaks with Holly Stanton about indigenous materials and sacred geometries, from the seal of Solomon to the landscape of the American Southwest.

Holly Stanton: The average size of a painting in “Return” is between six and twelve inches. The paintings draw on the meticulous miniature-painting tradition of Pakistan. What brought you to this practice?

Murad Khan Mumtaz: I was born in Lahore and spent most of my life there—the city is a hub of miniature painting and other arts. I studied at the city’s National College of Art, the only institution to give a BFA degree in miniature painting. My interest in the technique had to do with my father, who is an architect and well known for reviving lost traditional Islamic building techniques using indigenous materials. I was inspired by that, this idea of “going back” to one’s precolonial roots, and the obvious choice was to find that through my own form of expression, miniature painting.

HS: Is it still relatively common to study and practice this technique in Lahore? How is the reading or reception of this art changed in a contemporary context?

MKM: The medium has been revived, actually. During and after the colonial period, almost all traditional art forms on the subcontinent suffered because of the advent of modernity and industrialization. After the birth of Pakistan in 1947, the country consciously followed Atatürk’s model of a modern Islamic state, which left little room for tradition. Like most other precolonial art forms, miniature painting slipped into obscurity. It was only in the 1980s that miniatures were brought back to life by Bashir Ahmad, who studied with Pakistan’s last master of the tradition. However the revival, which took place in a modern art school environment, came with a price—students practicing contemporary miniature are encouraged to incorporate aspects of postmodernism and subvert the tradition. I see tradition as something that can be practiced without sarcasm or irony. I think tradition is a lived experience, an existential experience.

HS: What experience did you draw on for the landscapes of “Return”?

MKM: I made these paintings during a residency at the Santa Fe Art Institute last year. Right after I finished the Columbia MFA program in 2010, I traveled to the Southwest with my wife, Alyssa Phoebus, who is also an artist. I became fascinated with Native American traditions and the many parallels between those cultures and my own. I started painting these idealized landscapes, thinking of what it must have been like three or four hundred years ago—and what it may be like in the future.

HS: These paintings have a strong visual relationship between vast landscapes and symbolic imagery. Do the symbols and geometric frames within each work carry a specific meaning or weight in the context of Pakistani culture, or do you see them operating universally?

MKM: A bit of both. I am fascinated by Semitic symbols, such as the seal of Solomon, which is two triangles coming together to make the six-pointed star. I’m also interested in the links between symbols and colonialism. For example, the crescent that is often seen in southwestern imagery came from the Moorish culture in the south of Spain. But what really interests me is to understand the underlying links between disparate premodern cultures, and how the sacred is expressed through the visual language of symbols.

HS: The framing and geometry within each work in “Return” resemble the passport interventions of “Origin, Departure,” the project you and Alyssa published in Triple Canopy. Could you explain the use of sacred geometry in these bodies of work?

MKM: In “Origin, Departure,” we looked into geometric structures used for sacred art in the Muslim context. Calligraphy and geometry are the two essential sacred art forms. My Pakistani passport is filled with geometric symbols, most relating to the sacred geometry that exists in mausoleums, mosques, and sacred architectural manuscripts. Today that imagery, as it exists in the passport, has been manipulated, distorted, voided of meaning, so as to symbolize the Muslim state. One of the main focuses of “Origin, Departure” was to return the meaning of this beautiful visual language. Most of the preexisting images within the passports are arches and dome designs, which I see back home in traditional buildings. That’s what inspired me to use these borders and internal frames in the paintings in “Return”: They serve as architectural spaces and windows onto the work.

HS: The “Return” landscapes are marked by the evidence of human production, but human forms are absent from the work.

MKM: The paintings contemplate disappearance and remembrance. Someone has done something, but has disappeared, leaving behind ruin and a haunted space. I also think of “Return” in relation to the omnipresence of Western powers, globalization, and colonialism.

HS: In recent years, you and Alyssa have worked primarily with natural and traditional materials, with an exacting attention to detail. The cross section of your techniques is evident in “Origin, Departure.” Has this collaboration engendered new processes and directions in your individual bodies of work?

MKM: Definitely. Alyssa has always had a formal approach to her work—everything is laid out in a very precise and geometric pattern. In “Return,” I made every painting on a grid; I was inspired by how she draws. The hand is essential to both of our practices. And now we’re itching to go back to “Origin, Departure” materials and rework them in the form of a book or large-scale paintings.

HS: Because your practice is so deeply rooted in traditional techniques and materials, how was your experience working in a digital format for “Origin, Departure”? Do the images in “Origin, Departure” exist in a physical form?

MKM: The Triple Canopy format, which resembles a book and moves horizontally, prompted us to develop an abstract narrative arc within the project. This played to our strengths: With miniature painting, I look at art as an illustrative format. Traditionally, miniature painting came about only as support for text. Most of our interventions have to do with bringing back aspects of illumination, which always supports sacred calligraphy.