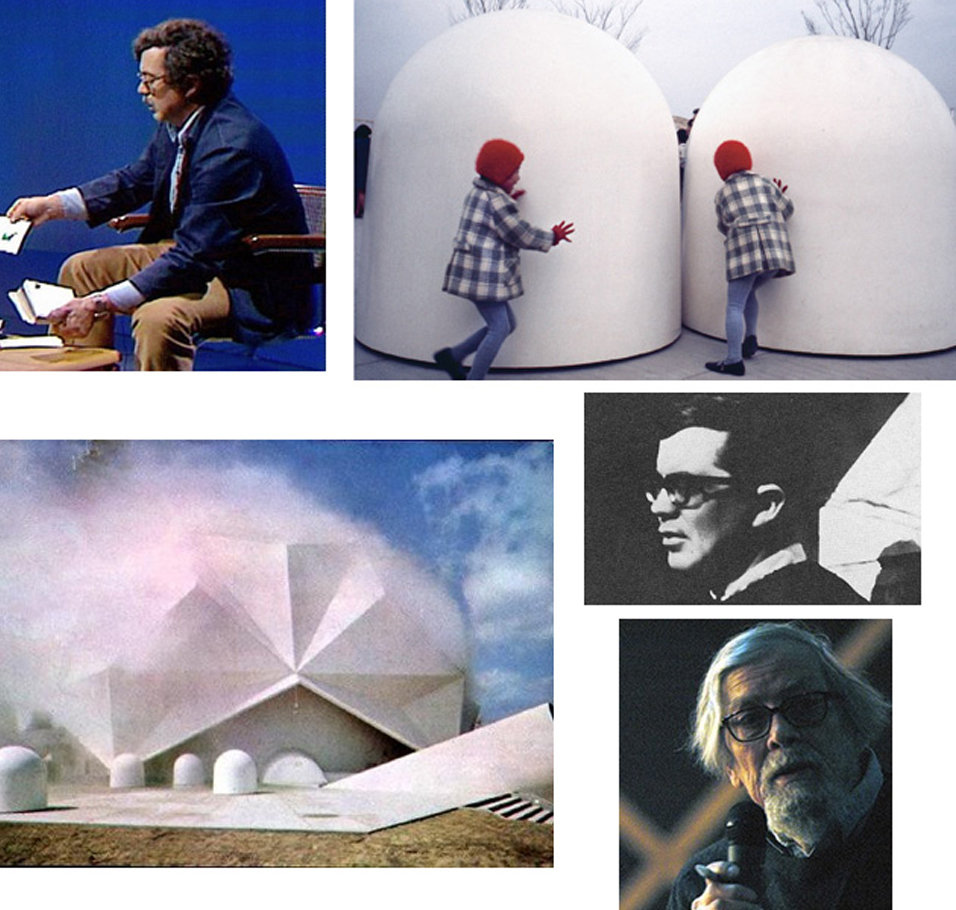

Clockwise from top left: Robert Breer showing his index cards on Robert Gardner's television show "Screening Room," 1976; two of Breer's floats at the World's Fair in Osaka, 1970; a photograph of Breer as a young man; a recent photograph of Breer; floats outside the Pepsi Pavilion, World's Fair, Osaka, 1970.

Clockwise from top left: Robert Breer showing his index cards on Robert Gardner's television show "Screening Room," 1976; two of Breer's floats at the World's Fair in Osaka, 1970; a photograph of Breer as a young man; a recent photograph of Breer; floats outside the Pepsi Pavilion, World's Fair, Osaka, 1970.

One of the highlights of Triple Canopy’s residency at the Tucson Museum of Contemporary Art last year was a screening of Robert Breer’s experimental animated films. Breer, who passed away last week at the age of eighty-five, made his first films in Paris in the mid-1950s and spent most of career in and around the New York art world, before settling in Tucson in recent years. On the day of the screening he invited a few of us to visit him at his home and studio in the foothills west of town. It was an unusually foggy morning, and our drive to his modest ranch house through the cloud cover felt like a pilgrimage to see a suburban mystic—a great artist living amid the desert sprawl.

But aside from a short white beard and perspicacious wit, Breer hardly fit the model of artist-as-sage. Perhaps because he worked in animation—a medium tied at least on some level to cartoons—his work always seemed to eschew the aura of self-seriousness that bogged down so much avant-garde filmmaking (or at least the critical rhetoric surrounding it). In person, Breer was patient with our questions and generous with his time. He insisted on preparing coffee, toast, and microwaveable breakfast sausages. His hearing had faded, but he could talk for hours. At the time, he was planning a series of large retrospective exhibitions in Europe. As we ate in the kitchen, he told stories about his dog and recounted a career that intersected with many of the major artistic developments of the latter half of the twentieth century, though the significance of his work has only recently begun to be fully acknowledged.

Over the course of his sixty-year career, Breer’s constant concern was dynamism in art. Every inch of his animated films, which initially developed out of abstract painting, pulses with movement. These works are tied to the history of kinetic art in the 1950s and ’60s, but they found equal resonance with the theatrical happenings organized by his collaborators in New York, chief among them Claes Oldenburg. And while the ecstatic visual language that Breer developed was central to the hermetic world of the avant-garde—Breer was a founder of the Film Makers Cooperative—it also drew the attention of later pop musicians like David Bowie and New Order, who worked with Breer in the 1970s and ’80s to explore the emergent genre of music videos.

Breer famously composed most of his films one frame at a time by photographing individual drawings he made on index cards. Thousands of these drawings were filed away in his Tucson studio in what looked like old card-catalogue cabinets. As we asked about his films he would reach into the files, pull out a sequential handful of cards, and make an impromptu flip book, animating a short clip with his hands. The setup recalled the earliest days of cinema, when filmmakers would submit still prints of every frame of a movie to the Library of Congress for copyright purposes and, eventually, preservation. One can only hope that Breer’s trove of drawings will find such a home.

Although he produced his last film in 2003, Breer continued to make the kinetic sculptures he called “floats” through the last years of his life. Beginning in the late 1960s, when he was involved in Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.), Breer mounted minimal plastic forms on motorized wheels. Set in motion, these objects essentially animated the entire space of the gallery. He showed us a few of his most recent works: small pieces of Styrofoam and rumpled plastic sheets that rolled across the floor at almost imperceptibly slow speeds. His dog had apparently made a wary peace with these things, but would occasionally become startled and half-bark at the alien objects creeping across the ground.

Breer attended the screening that evening to talk about some of his best-known works for the Tucson audience. He was self-deprecating, gracious, and hilarious, pointing out whenever he could the erotic undertones—“horny” was his term—of his otherwise playfully “dynamic” animations. Given his trouble hearing, I wasn’t sure how the standard Q&A session would go. As people started raising their hands, I raced up to Breer with a pad of paper to scribble down the gist of the question. But he had a better idea of how to handle the situation: No matter what was asked, he launched into his own line of commentary on his work. He drew together personal anecdotes and decades of reflection but also managed to leave the audience roaring with laughter, garnering a kind of genuine appreciation—for his work and his presence—I’d never before seen in any gallery or museum, and am unlikely to see again.