On the evenings of April 23–25, 2010, New York-based theater collective Group Theory probed the psychosonic landscapes of Herman Melville’s classic novella Bartleby, the Scrivener in an intimate chamber ritual that transforms the private act of reading into a communal encounter. A strange literary-theatrical hybrid, Bartleby. A Rereading is a palimpsest of readings, a hyper-lucid window onto a famously difficult text in all its haunting ambiguity and violent comedy. Each performance was followed by drinks and conversation with invited respondents, including Paul Chan, Edwin Frank, Lynne Tillman, Abha Dawesar, John Bryant, Vivian Gornick, Joseph McElroy, Alice Boone, Graham Parker, Molly Springfield, McKenzie Wark, and Greg Wayne. Below are condensed and edited excerpts from those three conversations, recently published in Invalid Format: An Anthology of Triple Canopy, Volume 3.

Sam Frank Bartleby decides he would “prefer not to” after being asked to proofread a copied document. In the story, rereading is complicated, ambiguous. I am by trade a copyeditor, which is not scrivening, but I do read a few thousand words an hour, and find errors and correct them. And if I’m at a magazine for a couple of weeks, I’ll reread the same thing multiple times. I was talking to someone I know with an MFA in poetry who, after copyediting for a day, couldn’t write poetry for a week. She said she was text-sick.

Joseph McElroy The repetitive, deadening nature of the work the copyists do is at the heart of this story. It’s not something that the narrator has fully grasped, fully felt. What was interesting to me when I reread the story was that it was almost as if Bartleby and the narrator were in a relationship: “I can’t make him leave, so I’ll leave.”

Vivian Gornick This is the greatness of rereading when you’re many years older: You are a different person. And so I’m shocked and thrilled to read the Bartleby that I read this week. When I was a kid I couldn’t get past the mysteriousness. This time I thought, at first, Bartleby is the lawyer’s story; but in time I realized it’s about the dynamic between Bartleby and the lawyer. The lawyer is not deceiving himself, but he only knows partially what he does, and what he thinks, and how he thinks; Melville brilliantly shows you the degree to which the lawyer understands what he’s thinking about and the degree to which he doesn’t. The lawyer is the essence of the Upper West Side liberal. [Laughter.]

What is Bartleby? He’s not real, none of them are real—they’re postures, they’re attitudes, ways of being in the world. All the lawyer wants is for Bartleby to be reasonable. This is the essence of what Bartleby cannot be. Bartleby is that which is not reasonable. Now, I say to you, if the lawyer was a radical, not a liberal, he would have gone the extra mile. He would have kept Bartleby no matter what. He would have known that Bartleby is the essence of rebellion, of the refusenik, of “I won’t live on your terms,” of “in fact I’m not even sure if I want to live on any terms.”

John Bryant Unfortunately, the radicals of my generation are now working on Wall Street.

Gornick That may be. Indeed, most people become the lawyer.

Frank The difference between reading and rereading is present in Group Theory’s Bartleby, but so is not-reading—not the lack of literacy or of the resources required to be a reader, and not just a basic indifference, but a preference. “The art of not reading is a very important one,” Schopenhauer wrote. “It consists in not taking an interest in whatever may be engaging the attention of the general public at any particular time. When some political or ecclesiastical pamphlet, or novel, or poem is making a great commotion, you should remember that he who writes for fools always finds a large public. A precondition for reading good books is not reading bad ones: for life is short.” When we talk about rereading we can also talk about not-reading; they’re somehow closely related.

Ben Vershbow (director) I had been entranced by Bartleby and by Melville, and naturally I wondered: Can we take a single room full of people and turn the story into a shared encounter? The story resists that at every turn. We kept coming back to Bartleby, this pivotal non-presence: You can’t cast him, because then he’ll lose his eternal ambiguity. We ended up reading the story again and again, and we realized that reading together was a really interesting experience. We could share what is generally a solitary activity. We found these rhythms, and found that it made sense to maintain the singular voice of the story and not to turn it into a play, with different characters exercising their volition on the stage.

MCELROY I think the metaphor that the director came up with is a very good one because it keeps the focus on reading the words. Indeed, on rereading the words. At the end, prefer becomes the word they can’t not say—as if it’s contagious. The performance is all about being aware of the words, being puzzled by the words; reading with the eyes, reading with the voice. My question is whether this changes our sense of the story.

BRYANT I gathered during the break,in conversation with two of the actors, that when the performers are reading, they haven’t determined who is going to read which part, and that the overlapping is done through improvisation. This was done so tightly. It seemed like each overlapping reading and each change had meaning. And now I’m discovering that it’s not going to be this way next time. My question is: What!? This is amazing.

Vershbow It was an amazing process for us to discover this method of reading the story, where we decide that half of the story will be read aloud by multiple people at once and let the other half be up for grabs. This method evolved from reading the story again and again. We had rehearsals where we discovered great things, we had rehearsals where we discovered nothing, but the one thing we always accomplished was to read the story again. The actors are in tune with each other in incredible ways. They’re listening to each other’s breaths. This creates the effect of the performance being the same, very reliably the same, but also very different each night. And this is interesting to us, and in some ways honors the story, which is part of a distinct subcategory of literature: It has no meaning. The thesis is that there is no thesis.

GORNICK The pauses you developed were extremely intelligent. They accomplished a huge amount and really focused our deepest attention on what we could not understand completely, only feel. It isn’t that the characters are without roles; it’s that they’re trapped, deeply trapped in their positions, in their essences, whatever they are. The lawyer is the best that he can be, and Bartleby is, too. They’re on a collision course. It can’t be helped.

Jeremy Beck (actor) Not designating certain parts was our attempt to get out of the way. When you have parts that are up for grabs, the performance will naturally be different every night. We surprise ourselves all the time. We also wanted stretches where audiences heard one voice, where you could just sit with one voice for a little bit, because otherwise it seemed unfair to the story.

Paul Chan The rhythm of how one takes in information becomes different when it’s embodied, especially in multiple bodies. It was exciting when the voice of the narrator splits, because you realize he’s inhabiting three or four different personalities.

Lynne Tillman I’m struck by your sense of rhythm. In your own work, you’re often editing great swathes of material. Do you see a kind of syntax in the movement from one edit to another, from one kind of rhythm to another?

CHAN I’m going to sound ridiculous, but it’s about sex. Rhythm is a movement of sexuality over time without a body, and it’s what keeps us in love, it’s what keeps us focused. I think the work that I do with the animations and projections, regardless of whether it’s a form or a shape that I’m trying to represent—if it moves over time it has to have a different rhythm. It has to work in relation to other, different things; this is what holds one’s attention.

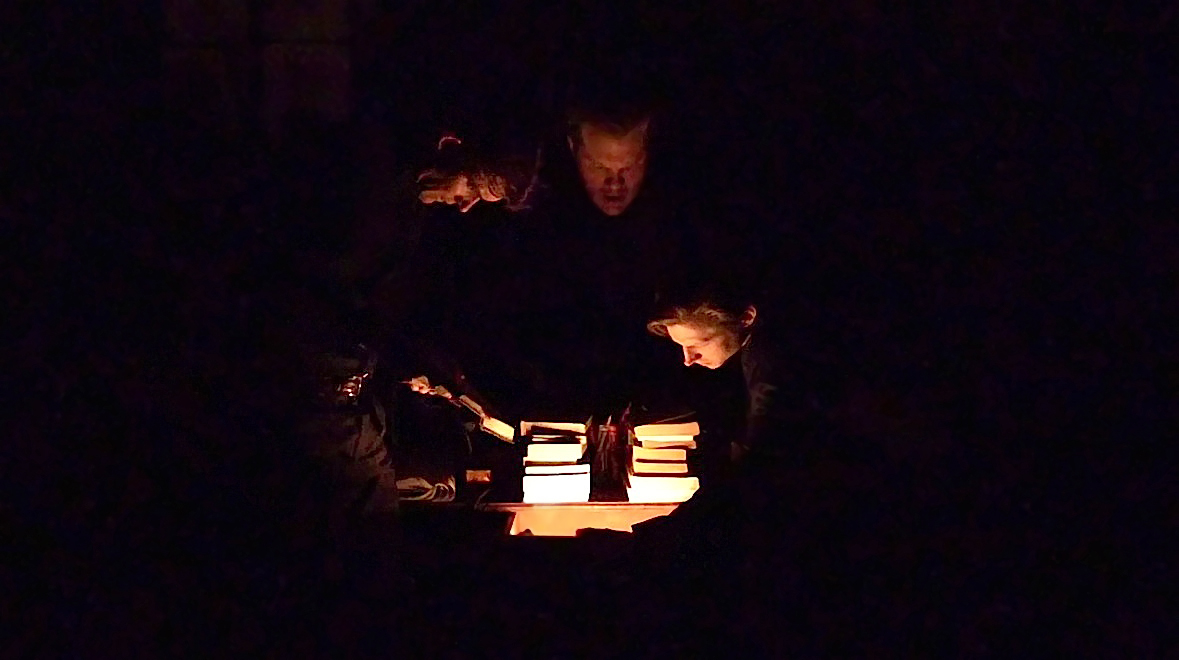

TILLMAN I do want to say something about the use of light in this performance, the agency that each actor had to press the button and turn the light on and off; the light would illuminate different parts of the text, different faces, creating an experience you don’t get from reading the book. There were physical sensations that would be very hard to produce with words. And you were improvising, which is also hard to do in writing. As a novelist, it’s often very disturbing to me that I can’t really affect the reader’s environment, turn off her lights.

Vershbow We used visuals for the most part to create a support for listening. When you’re listening to the radio, your eyes rest on something, and you’ll visually engage with that thing in a subconscious way. We were trying to provide something for the eyes to intuitively rest on while the ears open up. And this story is very hard to penetrate at first, hence the movement from darkness to more illumination.

Chan For me, it was less a matter of providing a visual anchor so that we could concentrate on the words, and more about complementing the rhythms of the words themselves.

McElroy I have a long essay, which I may never finish, about rereading— about missing that the first time, about remembering how I felt, and about how this remembering distracts me from what I’m reading. And so what Vivian said about rereading much later a book you first read at an earlier age is very poignant to me.

GORNICK I have had the experience of rereading a book every five or ten years and each time identifying with a different character. In those experiences the fullness of the book is clear. It becomes your life. And you realize it’s a great book.

Tillman I was 13 when I read The Catcher in the Rye for the very first time. I thought to myself: I’m going to read The Catcher in the Rye every year or two, because I always want to stay attached to the teenager I was at that moment. At a certain point I stopped. I really couldn’t stay attached. I could still admire The Catcher in the Rye, but I couldn’t stay connected to the text, which was disturbing.

Edwin Frank I think rereading is often tied up with recreating a certain feeling and community, which is a talent particular to adolescence—it becomes harder and harder. I edit children’s books, and it’s interesting to go back and read books that you remember from childhood as just bursting with imagery and implications. These books are often written very stupidly. They’re like coloring books. But your imagination just fills in the spaces. As an adult, your jaded imagination wants more; you go back seeking that world only to find that it is gone.

Graham Parker I first read Bartleby as a student, and it’s been a touchstone for me in my own work for years now, as this site of unknowable resistance. Bartleby’s character is really useful for me in thinking about types of relief portraiture where something gets revealed because of the way the work resists processes that act upon it—in this case juridical or legal processes. And there’s this unreliable narrator who is forever trying to read Bartleby in a way that satisfies his need to discipline the man.

Greg Wayne In the mid-’90s, my brother was a copyeditor for a law firm. He thought it’d be a great idea if he quit his job by reenacting Bartleby. He was given documents every day, and for a few days he said, “I would prefer not to.” His boss came in, and was like, “Are you sick? What’s going on?” And he would say, “No, I just prefer not to.” Finally the boss asked, “Would you like a raise?” [Laughter.] Then my brother was sent to the psychologist, and whatever the psychologist preferred he do, he’d prefer not to. And then he was just canned. To me, the novella became a really great way to quit a job.

Mckenzie Wark Bartleby is about a certain kind of labor: You can force people to do physical labor, but it’s very hard to get people to do mental labor. They have to be engaged. As someone who has gone to the dark side, who has been a manager for the last year, I really identify with the narrator. How the hell do you get people to do this stuff? Because, after all, it’s boring! “OK guys, we have to sit around and make a document together.” We can caffeinate them, that works.

Daniel Larlham (actor) Our rehearsals were actually really boring at the beginning! Maybe this has to do with the fact that, in the kind of Americanized Stanislavski tradition in which I’ve been trained, the idea of the actor as reader—as an intellectual who gives intonation to a line of text rather than someone who has a life from which these words just organically emerge—is very negatively charged.

Wark But you get a different reading every time you perform a play, however miniscule. Actors say there’s a moment when you can go off-book, but this is not what you did. You are the book.

Vershbow I met someone recently at Amherst who teaches a class in which his students select one painting to engage for the entire semester. They each choose different works, and they have to be able to access them physically so they can view them multiple times. By the end of the semester, they haven’t just consumed their chosen work, they haven’t been distracted by it, they haven’t been entertained by it; they have a relationship with the work that’s dynamic and multilayered. This feels analogous to how we threw ourselves at this text over and over again to create a way of sharing it and opening it up.

Audience Member There are huge swathes of Bartleby that rephrase Shakespeare, Thomas Browne, Lawrence Sterne. The books that remain from Melville’s library that are available in public collections are full of underlinings. For Melville, rereading is very close to rewriting. We can talk about Melville’s own repurposing of his rereading as an excavation of process. You realize that Melville is scrivening someone else’s language; You recognize the reference, but then he skitters away from it into his own writing, and you wonder if he felt that he was too close.

Tillman Paul, when you organized Waiting for Godot in New Orleans, that was a massive rereading of the play post-Katrina. I always wondered: How did you get Beckett’s estate to sign off?

Chan We didn’t tell them. They’re notoriously strict about reinterpretations. The estate essentially says: You have to read this the same way as it was originally read. We sent them a generic adaptation; we just told them we were going to perform the play in New Orleans. But every reading is a rereading; something happens to you as you reread a book again and again over the years—the rereading becomes more about you than the book. The text hasn’t changed, but I have; and so every rereading is a measure.

Molly Springfield I recently used all the existing English translations of Proust’s In Search of Lost Time to piece together my own version: twenty-eight 11" x 17" graphite drawings of photocopies of those editions. A careful reader of my “translation” would start to notice the repetitions and omissions from page to page, sentence to sentence. I wanted to ask how we experience memory visually, though through something that is read. But when I’m making the drawing I’m not actually rereading the text—that would be too painful; I’m rewriting by drawing.

Wark I do hundreds of drafts of every single sentence. I’m trying to drive copyeditors insane. To go back to the gentleman’s comment: All writing is plagiarism, there’s no originality whatsoever. Occasionally you meet writers who insist on originality, but it’s like, Have you invented a new alphabet system? Have you invented an entire language? No, you’re writing a book in English, so you’re using words other people have used. You’re using whole phrases other people have used. You may have whole sentences. Rewriting is the gig. It’s all about the well-chosen word. The poet Lautréamont talks about this: Plagiarism is necessary, progress implies it. It’s the slight alteration that makes all the difference. In other words, language is common property, it belongs to everyone.

“The Scrivener's Business” was published as part of Triple Canopy’s Research Work project area, which receives support from the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, the Brown Foundation, Inc., of Houston, the Lambent Foundation Fund of Tides Foundation, and the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council.