1

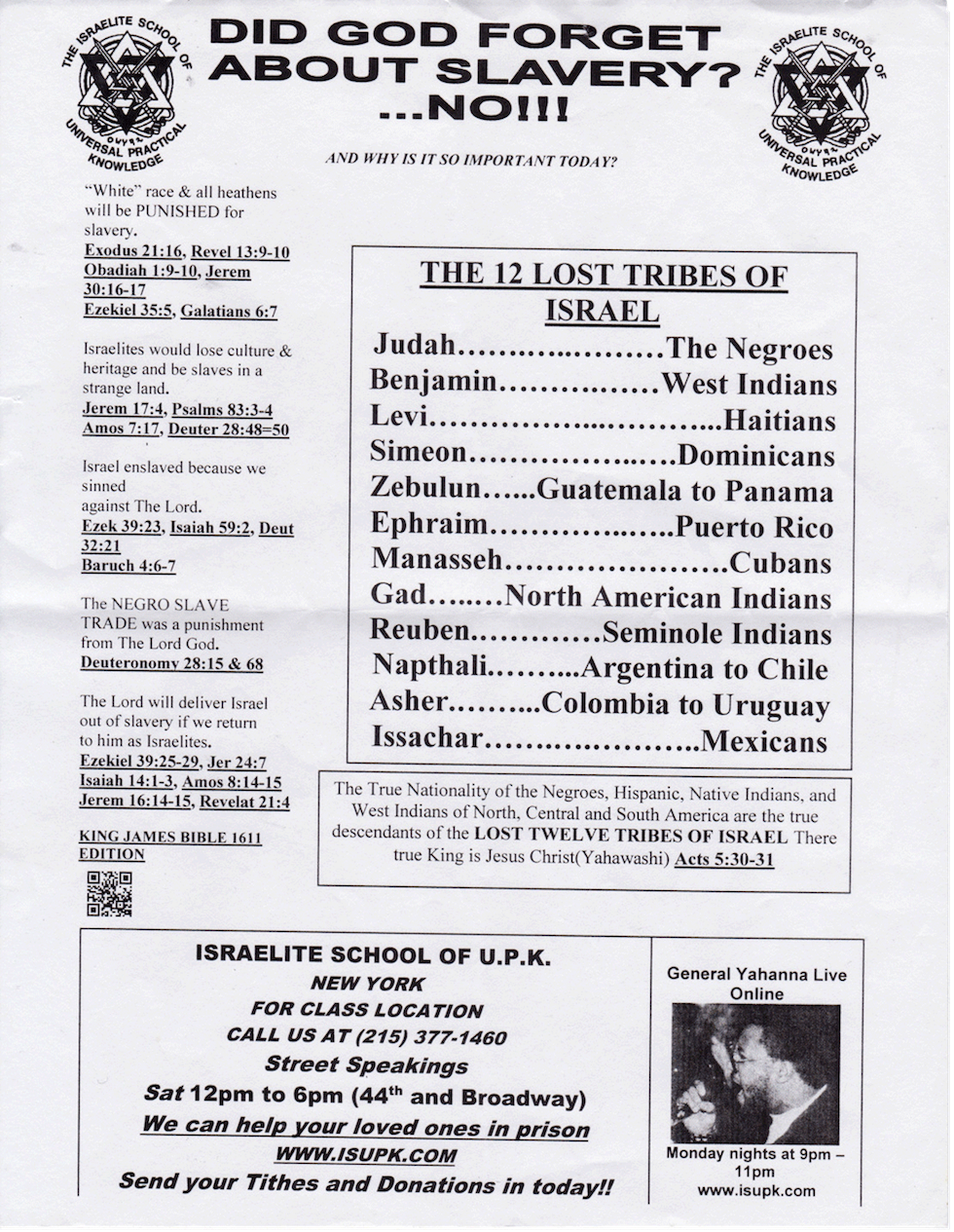

It is August in New York City, and it is hot. The street preachers, stationed at crowded intersections and subway portals, seem to disregard the weather: They wear three-piece suits, ankle-length gowns, and layers of sweatshirts listing deadly sins. Some are combative and eagerly engage pedestrians, while others are meditative and patiently wait to draw an audience. An older black gentleman, dapper in a freshly pressed gray suit, stands at the entrance of the Union Square station with a sign that professes: “Sin is an amino acid cluster in the eye that prevents the absorption of God’s bright light.” A middle-aged Barbadian man on the back of the B44, headed into Bedford-Stuyvesant, joyfully delivers a rhyming sermon—“The gates of hell shall not prevail!”—as young kids pile on to the bus. Black Hebrew Israelites stalk the sidewalks of Harlem and, with increasing regularity, Brooklyn, dressed in robes, caftans, and fringed pants, which are liberally ornamented with the Star of David.

These preachers convert public space into pulpits, and hawk seemingly endless supplies of photocopied pamphlets and self-published books. Sometimes, with the help of microphones and handheld speakers, they barrage passersby with proclamations about the black man having descended from the ancient Israelites. They rhythmically shift between fast, faint murmurs and measured enunciation. They repeat God so as to create a reverberating, guttural tone, which competes with the noise of passing cars and halal food-cart vendors listing meat-and-rice combinations for tourists.

Roaming New York, I’m struck by the range of black religious doctrines on offer from these street preachers, which speaks to a common dissatisfaction with conventional creeds (and the churches that propagate them). But perhaps more curious is the desire of the preachers to make public their refusal of allegiance, and their drive to engineer and endorse new traditions.

2

My father, at the age of twelve, lost in a sermon at his mother’s Methodist church in Northern California, looked up and saw Jesus: a strange white man hanging in a crooked, gold-plated, plastic frame, suspended high above him. He became disenchanted that day, and spent much of his adolescence skipping church in favor of games of pool at the Boys and Girls Club. While my father’s parents, who moved to San Francisco from Texas in the 1930s, during the Great Migration, maintained their faith, he sought a new spiritual path. Shuffling between religions in California in the late 1960s and 1970s, he recalls feeling like he was at “a buffet, going from community to community, never really feeling full.”

Finally, in the fall of 1982, he joined the East Oakland mosque of Imam Warith Deen Mohammed. Mohammed had replaced his father, Elijah Muhammad, as the Nation of Islam’s leader in 1975. The next year, he disbanded the organization, rejected the divinity of its founder, Wallace Fard Muhammad, and urged his followers to adopt what is often identified as mainstream Sunni Islam. At twenty-nine, my father took his shahada in front of Mohammed’s congregation of Black Muslims and changed his name from Ricky to Kamal. My mother soon joined him.

When my mother speaks to me about attending church as a child, she tells stories of preachers who promised joy and freedom after death. A future without suffering, she remembers, could not be secured on earth; the patient and the pure would have to toil in this world. Later, she began to wonder: What if death were not a prerequisite for joy and freedom? What if there were a theology that offered a different kind of future?

3

When I was fifteen, I heard the story of Noble Drew Ali at my East Oakland mosque—one of more than a hundred Imam Warith Deen Mohammed masjids—in a class on the history of Islam in the United States. Born as Timothy Drew in North Carolina to ex-slaves and, possibly, Cherokees, Ali declared himself to be a Muslim prophet, preached salvation on street corners in Chicago, propagated an origin story in which black people descended from the Canaanites, and in 1913 founded the Moorish Science Temple, which eventually attracted more than thirty thousand followers. In class, Ali was presented as a sympathetic figure, as he represented the beginning of an Islamic lineage that encouraged self-determination for black people; yet he was also a heretic, as he promoted a notion of prophethood that conflicted with Islamic orthodoxy. According to my religion, to claim to be a prophet was to break the Khatam an-Nabiyyin, or “seal of the prophets,” which ensured that Muhammad was the last of the prophets sent by God. Ali, then, was a rogue who disrupted the carefully drawn boundaries around authentic Islam. I admired his audacity.

Ali’s movement began in Newark, New Jersey, but in 1925 he moved to Chicago and incorporated his organization as the Moorish Science Temple of America; the official mission was “to uplift fallen humanity and teach those things necessary to make men and women become better citizens.” It was only five decades after the legal abolition of chattel slavery in the United States and during the Great Migration, which proved to be fertile ground for religious leaders who forged alternative visions of black life in the country. Michael Gomez, in Black Crescent: The Experience and Legacy of African Muslims in the Americas (2010), calls the period from 1910 to 1940 “an age of unorthodoxy.” (The Nation of Islam was established by Wallace Fard Muhammad in Detroit, an epicenter of the Great Migration, in 1930.) Government agencies and mainstream churches—which often mutated in a few years from humble storefronts into influential institutions and sources of social service for the indigent—largely failed to improve conditions for the millions of migrants who were packing into neighborhoods like Harlem and Chicago’s South Side. Organizations like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the Urban League empowered black communities but were dominated by members of the upper class (and regularly criticized for disregarding the political demands of the poor).

The NAACP and its cohort were met by “alternative organizations articulating different visions of both the terrain and objectives of struggle,” writes Gomez. Self-proclaimed prophets like Noble Drew Ali, Wallace Fard Muhammad, Dupont Bell, Father George W. Hurley, Father Divine, and Bishop Charles Emmanuel “Daddy” Grace, offered spiritual fulfillment and a different kind of representation. Their movements, whose popularity surged in the 1930s, have often been dismissed as unsophisticated and exploitative cults. But beyond being characterized as confused and uneducated, they were bound together by their efforts to respond to what Gomez calls an “ontological question of the first order” rooted in the black diaspora: The experience of migration forced black people to ask who they were and who they might become—on the level of the nation, the world, and whatever lies beyond.

Given my upbringing, when I encounter men on the streets of New York lambasting sinners and promoting gospels, I think of the idiosyncratic religious communities—and lineage of black prophecy—to which they belong and which are obscure to most passersby. In order to address the overall conditions and existential concerns of black people, Ali and his contemporaries called on religion, politics, philosophy, art, music, and costume, among other resources; they alloyed fragments of ideologies, scripture, spiritual maxims, and economic agendas. Now, I wonder, what draws black people to the Moorish Science Temple, and what makes them stay? Can these movements—or whichever nascent movements have yet to impinge on my consciousness and have yet to be named—promise a future that outshines those on offer by the National Baptist Convention or African Methodist Episcopal Church? Can they, at least, provide the satisfaction of self-invention and satisfy the will to write one’s own story?

4

Ali always maintained that the salvation of black people hinged on knowing where they came from, and that national origin had to do with the location of a homeland. His followers called themselves “Moorish American” instead of “black,” “Negro,” or “Ethiopian.” While they propagated Islam, their identities derived from the artful aggregation of historical narratives and belief systems. The Moorish Science Temple of America Collection (1926–67) at Harlem’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture includes many examples of rituals designed to instruct acolytes in Moorish history and tenets of the faith.1 One is Ali’s catechism, which includes “101 Questions for Moorish Americans,” as well as answers.

- Why are we Moorish-Americans? Because we are descendants of Moroccans and born in America.

- How did the Prophet begin to uplift the Moorish Americans? By teaching them to be themselves.

- What is our religion? Islamism.

- Is that a new, or is that the old time religion? Old time religion.

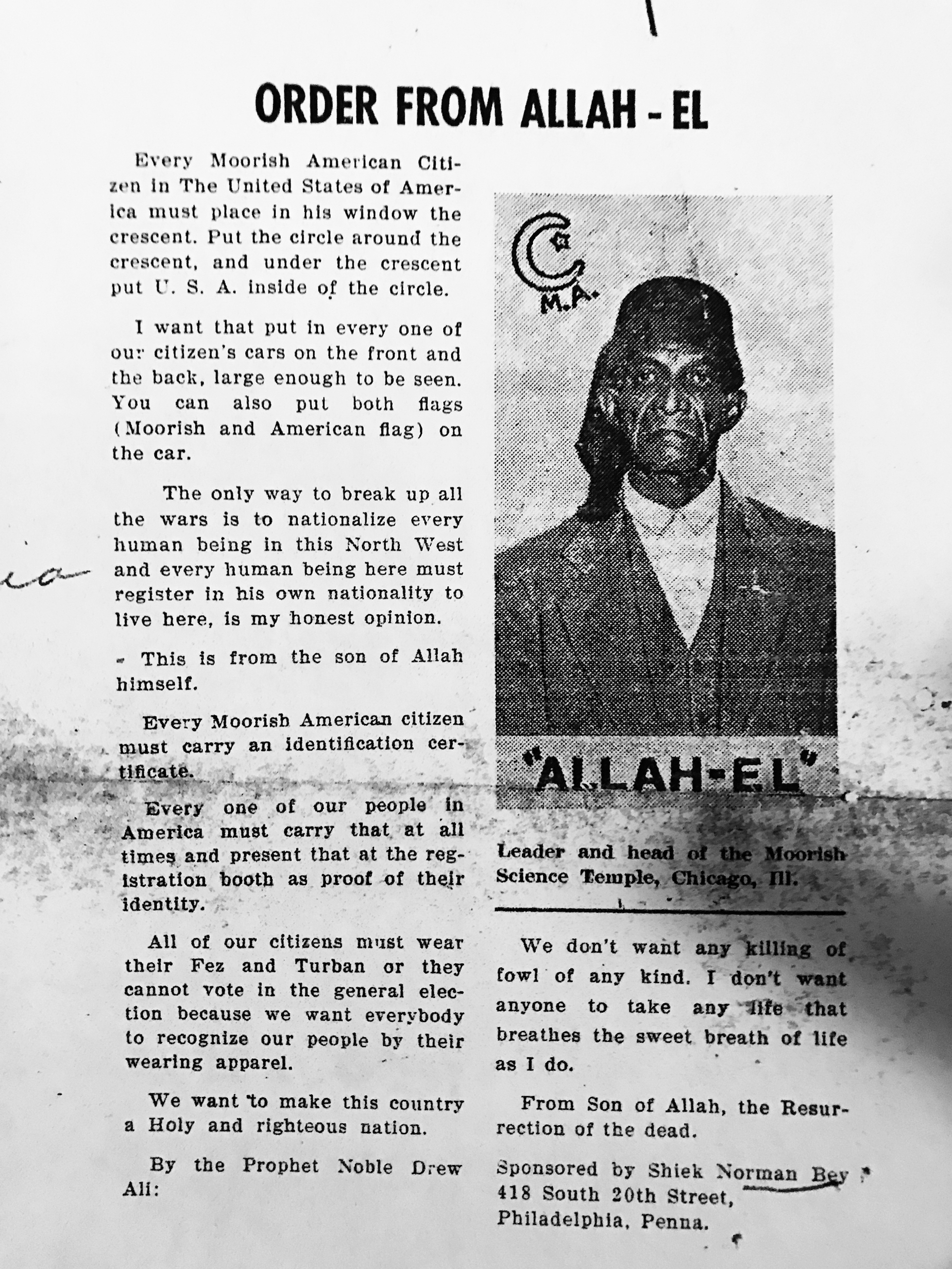

A flyer produced in 1927 advertises a “Great Moorish Drama” devoted to the importance of forging a new nationality, and was circulated by the Moors in Chicago. In addition to lectures by Ali and his acolytes, the event features Ali healing audience members and being bound by rope, like Jesus at the temple in Jerusalem, then escaping. The flyer attests to Ali’s interest in a form of evidence-based propagation that demonstrates spiritual authenticity: miracles. Like many early-twentieth-century prophets, Ali attracted followers by strategically introducing new ideas through familiar religious tropes, mostly related to the life of Jesus. The first nineteen chapters of his The Holy Koran of the Moorish Holy Temple of Science 7 (1927), the movement’s central text, are appropriated from the esoteric Ohio preacher Levi Dowling’s The Aquarian Gospel of Jesus the Christ (1908) (which Dowling claimed to have transcribed from the Akashic records); twenty-five chapters are taken from Unto Thee I Grant, a scripture of the Rosicrucian Order; and the last four chapters are penned by Ali.2 The full name of Ali’s book is The Holy Koran of the Moorish Holy Temple of Science 7, Know Yourself and Your Father God-Allah, That You Learn to Love Instead of Hate. Everyman Need to Worship Under His Own Vine and Fig Tree. The Uniting of Asia. “The title, a reflection of both the masonic signification of the number seven and the apocalyptic signs of the seven seals in the book of Revelation, also points to a logic of progressive revelatory understanding that intertwines the business of religion with the nationalist project,” writes Gomez. “That is, an accurate appreciation of the former is a necessary prerequisite for the eventual attainment of the latter.”

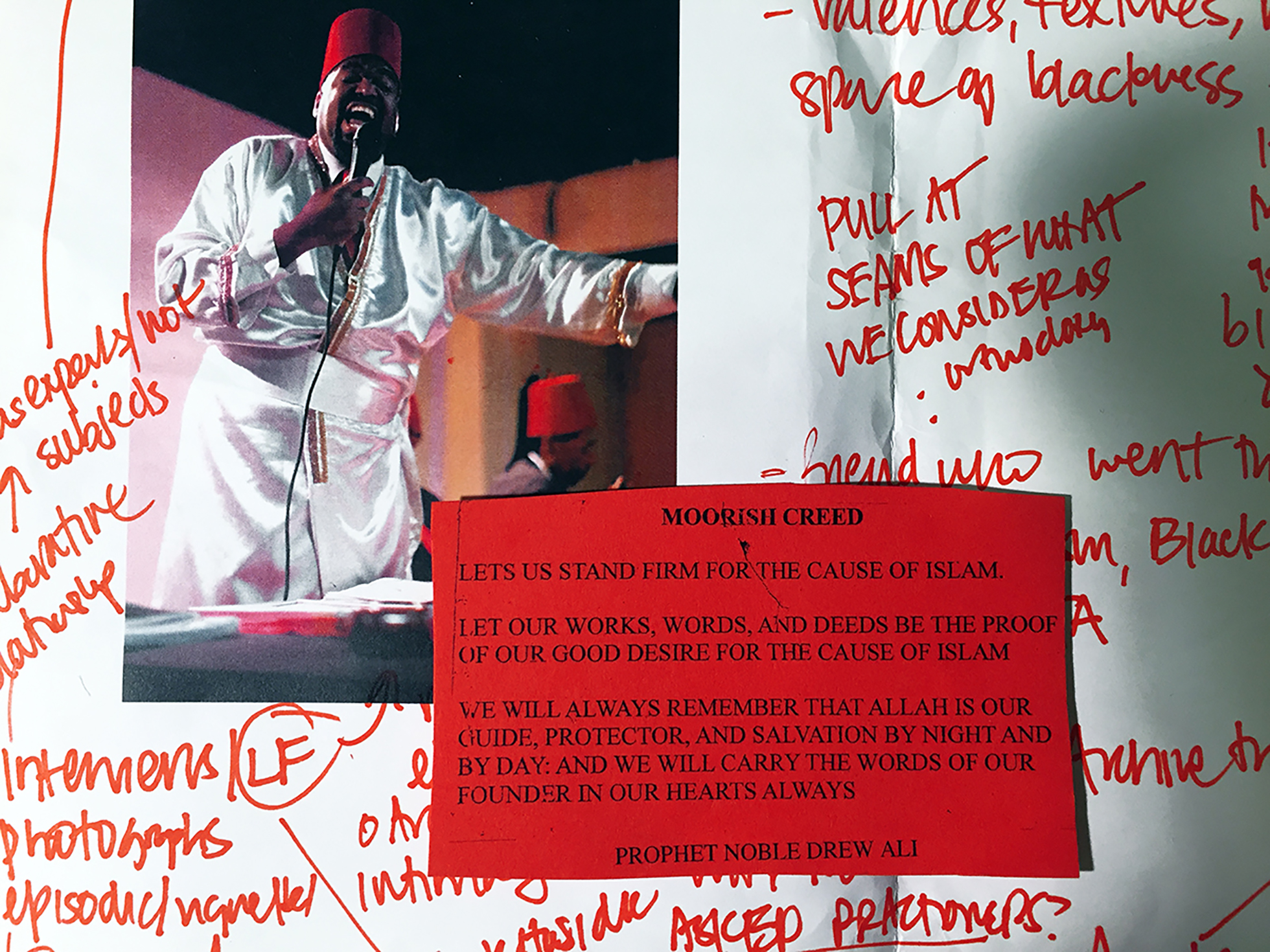

In shaping the Moorish identity, Ali often employed public and performative displays of community; the Great Moorish Drama was followed by parades, demonstrations, and lectures. In Chicago, Ali donned a fez while preaching on corners about black people being Moors and not negroes or Ethiopians. Those who joined the Moorish Science Temple of America were granted a nationality card that read:

This is your Nationality and Identification Card for the Moorish Science Temple of America, and Birthrights for the Moorish Americans, etc., we honor all the Divine Prophets, Jesus, Mohammed, Buddha and Confucius. May the blessings of the God of our Father Allah, be upon you that carry this card. I do hereby declare that you are a Moslem under the Divine Laws of the Holy Koran of Mecca, Love, Truth Peace Freedom and Justice. “I AM A CITIZEN OF THE U. S. A.”

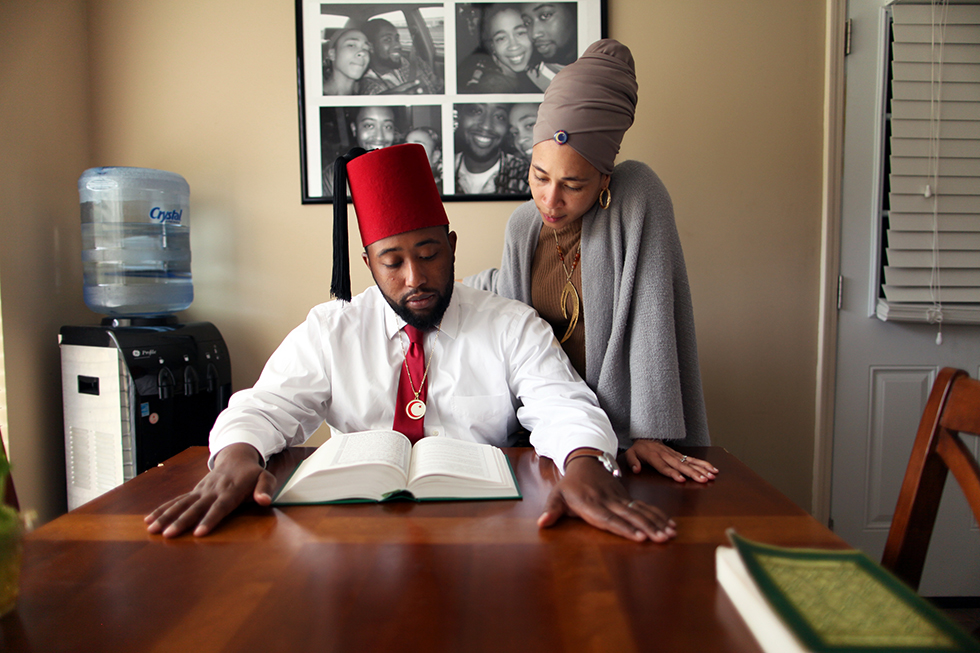

Cardholders possessed a new national and religious identity, which was accompanied by all the appropriate branding, most notably a red flag and pennant with a five-pointed green star at the center. (The points represent love, truth, peace, freedom, and justice.) They wore fezzes, which were popularized in the Ottoman Empire and appropriated by Western fraternal organizations, as well as buttons with the star and crescent, an ancient symbol commonly associated with Islam but also used by mystical orders such as the Shriners. During parades, they donned attire that symbolized the Islamic cultures of North Africa, the Maghreb, and Iberia: turbans, robes, and other regalia. They adopted the last names Bey or El: “free national names” that spoke to their Moorish heritage and rejection of the European names imposed on slaves.

Enthusiastic converts were said to flash their cards and announce their nationality to white people, which caused conflicts in the streets of Chicago. As a consequence, in 1928, Ali issued Divine Warning, which had to be read at every meeting of the Moors. “I, hereby inform all members that they must end all radical agitating speeches while at work in their homes or on the streets,” he writes. “We are for peace and not destruction. Stop flashing your cards at Europeans: it causes confusion. Remember your card is for your salvation.”

5

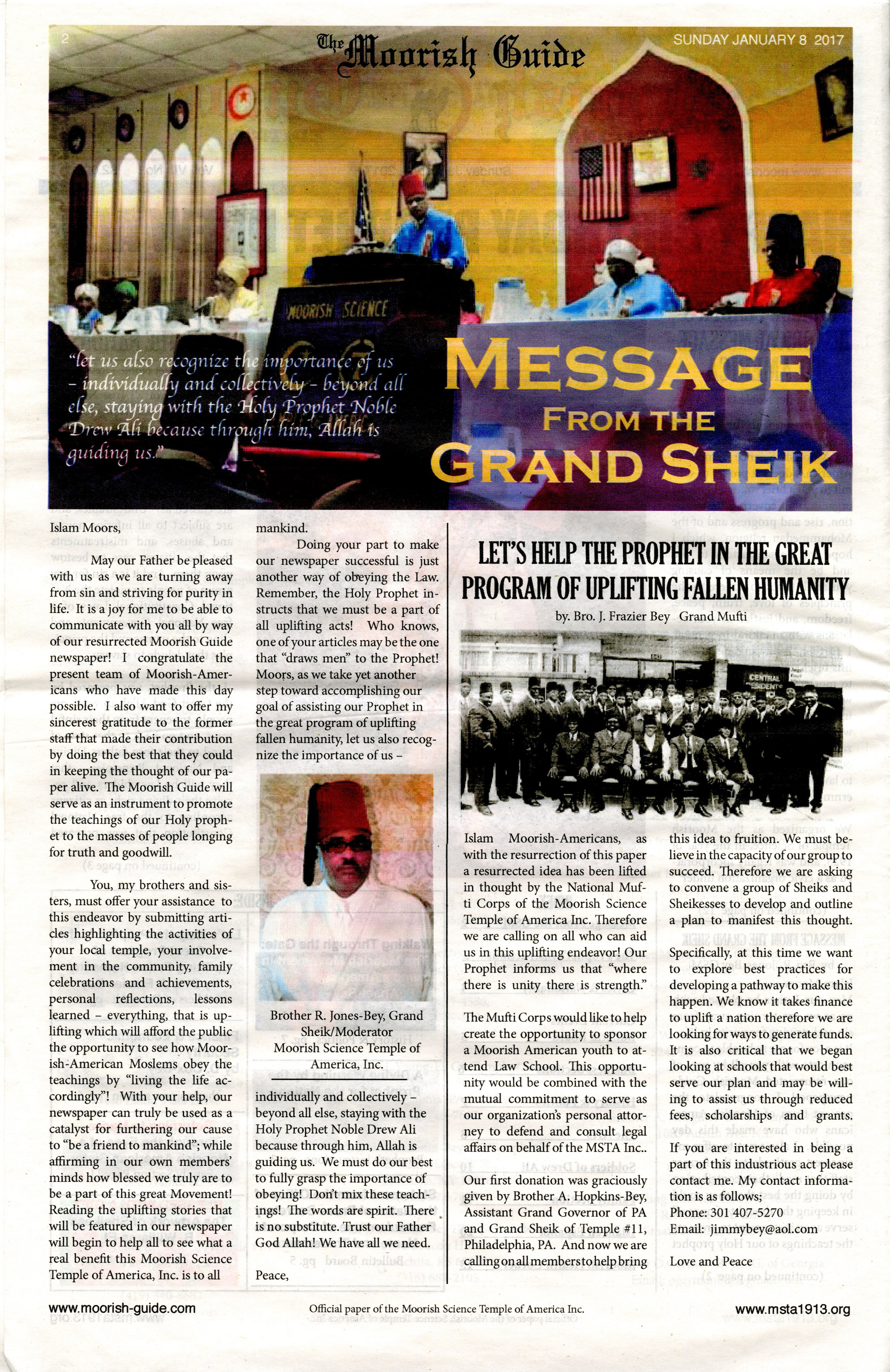

By the end of the 1920s, Ali had thirty thousand followers, who were concentrated in Chicago, Harlem, Philadelphia, and several cities in the South; he had also established temples in Milwaukee, Detroit, and Pittsburgh, and a network of Moorish stores and businesses. Ali had worked to expand the Moors’ influence by placing advertisements in the Chicago Defender, the popular black newspaper, for products made by Moorish Manufacturing Corporation, such as tea and blood purifiers. But in 1928 he started his own paper, the Moorish Guide, which he used to shape the identity of the movement, provide followers with doctrinal education, and unite temples. “The greatest weapon in the hands of our group today in America is our press,” notes a September 1928 editorial.

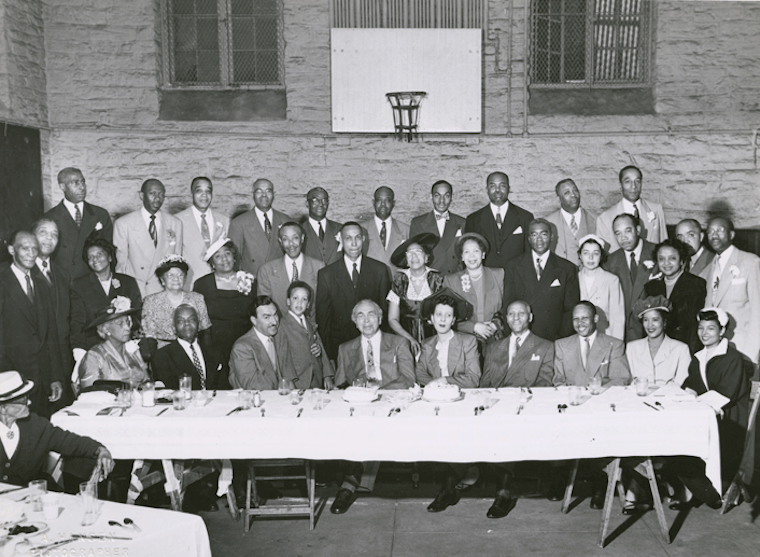

The legitimacy of Ali’s movement was cemented at the First Annual National Convention, held in Chicago in October 1928. Ali released a number of documents, such as The Divine Constitution and By-Laws, that formalized the religion, but without signaling an end to the development of its doctrine. (“Through accumulating experience each annual convention ought to witness a more perfect and wider functioning organization,” Ali told the Defender. “Constructive criticism from sympathetic friends in and outside of our ranks is welcome.”) Ali appointed a Supreme Grand Council to supervise the growing number of temples and led a Grand Parade that announced the arrival of the Moorish Science Temple as a community. At the end, according to Sheik Azeem Hopkins-Bey's Prophet Noble Drew Ali: Saviour of Humanity (2014), Ali “reportedly wrapped a little boy in the American, and a little girl in the Moorish flag, and subsequently declared the Moors a nation.” The Defender printed several stories about the convention, describing the organization as “playing a useful and definite part in advancing the sacred obligations of American Citizenship.”

The following year, the business manager of Chicago’s Temple No. 1 split with Ali, named himself Grand Sheik, and was soon stabbed to death. Even though Ali was out of town and meeting with a supporter of his rival at the time of the murder, he was arrested. Following his release from jail, he was found dead in his home; the death certificate listed tuberculosis as the cause, but some Moors claimed that he was violently beaten by the police who questioned him.

The ensuing leadership crisis is evident in the files of the FBI, which started tracking the Moorish Science Temple in 1931. The documents reveal the tensions between the perception of the Moors by insiders and outsiders—and the agency’s desire to exploit them. Investigators viewed Ali’s movement as a “negro cult” that was fixated on uplift and racial equality. On September 15, 1931, an FBI agent spoke with a Moor called Bey (his first name is redacted), who asserted that members “can identify themselves with these cards at any hotel or eating place throughout the United States, and be assured every courtesy and equal privileges with other races.” Bey claims not to be a negro; The Divine Constitution and By-Laws mandates that members “proclaim their nationality” and reject the titles of “Negroes, Colored Folks, Black People, or Ethiopians, because these names were given to slaves by slave holders.” “Bey,” the agent notes, “has all the appearance and characteristics of a full-blooded negro.”

Ultimately, the agent sought to discredit Bey and, by extension, the Moorish Science Temple of America. In a later file, an agent is said to have spoken with “reliable Negroes at Reading who characterized Bey as ‘Crazy’ and a fanatic and stated that he was considered more or less of a joke and no one took him seriously, not even the Negroes.”

6

On June 24, 2014, hundreds of people filled the theater at International House Philadelphia to see The Moorish Science Temple of America: Branches to Philadelphia, Rooted in Peace, a sixteen-minute documentary made by members of Philadephia Temple No. 11 as part of Scribe Video Center’s Muslim Voices of Philadelphia project. The documentary, shown alongside several films created by local Muslims about their communities, chronicles one century of the Moorish Science Temple of America through interviews as well as archival images and ephemera from private collections in Chicago. The film distills Ali’s teachings but also asks Moors why they joined the movement and how Ali’s brand of nationalism is relevant to their lives.

The film is aligned with the efforts of Ali and his Chicago acolytes to craft their own story, to adopt and adapt doctrines as necessary (without having their religion derided as flimsy or incoherent). Yet what the Moors say about Ali’s message in relation to Philadelphia circa 2014 is difficult to reconcile with the contents of manila folders kept in pristine boxes at the Schomburg Center. This is not so much because of our distance from Chicago’s South Side or Harlem in the 1920s and 1930s, but because the photocopies and newspaper clippings hardly grant access to “what is essentially and indescribably human,” to the “inner reservoir of thoughts, feelings, desires, fears, ambitions, that shape a human self,” as Kevin Quashie writes in The Sovereignty of Quiet: Beyond Resistance in Black Culture (2012).

I began to speak with members of Temple No. 11 about the work of self-representation last year, thanks to a friend who joined the community in 2012 after growing up as a Jehovah’s Witness and later converting to Sunni Islam. He introduced me to Hopkins-Bey, the grand sheik of Temple No. 11 and a proponent of Moors spreading and clarifying their doctrine through all available media. “You have a lot of hearsay,” Hopkins-Bey recently told me at the temple. “You have a lot of individuals taking a stance that’s not based on the orthodoxy as established by Prophet Noble Drew Ali. And oftentimes it’s an outside view approaching an interpretation of the teachings of Prophet Noble Drew Ali.”

In recent years, the most significant and damaging misrepresentation of the Moorish Science Temple of America’s doctrine has been the assertion—made by a minuscule number of Moors, some of whom have created offshoots, spread on social media and picked up by news organizations—that Moors, or “so-called black Americans,” constitute their own nation, as Native Americans do. The belief that Moors are members of an indigenous tribe and therefore are not bound by the laws of the state is in keeping with the sovereign citizens movement, a growing subculture that rejects the legal system and the payment of taxes. Many articles about this phenomenon have suggested that the Moorish Science Temple of America is an anti-government organization, which has prompted sheiks to issue statements disavowing the sovereign citizens movement and condemning those who manipulate Ali’s teachings. “The Holy Prophet Noble Drew Ali did not establish the Moorish Science Temple of America for its members to become anarchist or conspiracy theorist,” stated Hopkins-Bey in a 2011 press release. He then quoted The Divine Constitution and By-Laws, which insists that Moors “obey the laws of the government.”

This impugnment of the Moorish Science Temple of America is reminiscent of the widely publicized FBI investigations in the 1940s and 1950s, which spoiled the organization’s reputation and contributed to internal strife and the proliferation of factions. The Moors persisted, and their periodicals continued to promote Ali’s teachings, but the number of adherents—or those who were willing to publicly affirm their membership—fell dramatically. (I was unable to find accurate information about the size of the movement in the second half of the century; the investigations were compounded by the popularity of the Nation of Islam.) A few years before the Muslim Voices documentary, the Moors formed Ali’s Men, a group of writers and researchers from various factions, devoted to the creation of “cutting edge material for the defense of the Gospel of Ali.” For Ali’s Men, producing media is a pathway to organizing and unifying Moors and their temples. The group “provides a platform for brothers to come and, basically, get to know one another and get to learn to trust one another,” says Temple No. 11’s chairperson, Terrance Hopkins-Bey.

Azeem Hopkins-Bey’s Prophet Noble Drew Ali: Saviour of Humanity, a history of the movement from 1913 until Ali’s death in 1929, is one of the best-known works made available by Ali’s Men on Lulu, the self-publishing platform. The book includes an extensive discussion of The Holy Koran and the relationship between plagiarism, authorship, and sacredness. Hopkins-Bey asserts that Ali envisioned The Holy Koran as a complement to the canonical Qur’an; he affirms the status of the Moors as Muslims and disputes the accusations of deviance that have been made in countless books and articles and have tainted the image of the movement.

In response to critics of the Moors who have derided Ali for copying and have dismissed The Holy Koran, Hopkins-Bey contends that Ali “never claimed authorship” of the book, and “stated that it was ‘Divinely Prepared.’” In Hopkins-Bey’s account, Ali facilitated the delivery of knowledge harbored by Muslims in India, Egypt, and Palestine, which had been concealed until the time of Allah’s choosing. After all, the credibility of holy books tends to reside less in their authorship than in what people do with them. In American Scriptures: An Anthology of Sacred Writings (2010), the historian Laurie Maffly-Kipp observes that the Bible, the Qur’an, the Book of Mormon, and The Rise of Progress of the Kingdoms of Light and Darkness exist within constellations of social, political, historical, and economic phenomena, all of which influence how they are produced, disseminated, and canonized. “There is nothing in the nature of a text itself that makes it scriptural, rather it is the relationship between a text and a community that imbues a text with scriptural qualities,” she argues.

7

I spent several weekends in Philadelphia last year, attending celebrations on Prophet’s Day, which marks Noble Drew Ali’s birthday, and a march along Independence Mall as part of Moorish-American Remembrance Day, which reflects on the violence of slavery but also the reclamation of identity and heritage. As I spent time with the Moors, I watched followers record or stream videos of sermons and demonstrations, to be shared later on YouTube or Facebook, and I saw older women give students flyers to notify their schools that they would be absent on Moorish holidays. I quickly became aware of the extraordinary amount of archival matter that lives outside of (and may never be incorporated into) traditional collecting institutions. And I wondered how the ecosystem of archival projects initiated by members of the Moorish Science Temple of America—websites of the Geocities and contemporary variety, networks of YouTube channels, podcasts, Facebook groups, Instagram accounts—might not only elude but defy the principles and purposes of libraries like the Schomburg Center, whose white-boxed collections typically act as static repositories for a fixed number of documents and are meticulously managed and monitored.

Perhaps more than the clippings in folders, these ephemeral media and the narratives they form seem to reanimate the fundamental question raised by the Moorish Science Temple and so many of Ali’s fellow prophets: whether or not conventional Christianity can “offer blackness a future,” as the theologian M. Shawn Copeland writes in an article in South Atlantic Quarterly, “Blackness Past, Blackness Future—and Theology” (2013). “If so, how, and what kind of future?” Ali and others pointed to an alternative future by borrowing from Confucianism and Buddhism as well as Abrahamic faiths, by refusing all available options and embracing what was unfamiliar and amorphous. Copeland suggests that, today, we again ask, “How might blackness have a future?” She argues that “if the future of blackness rests in so reduced and truncated a past”—that of blackness as represented by Christian theology—“then such a future or futures remain bleak indeed. Is there a route blackness might take to a future with authentic and luminous possibility?”

The pursuit of a habitable elsewhere is the theme of Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower (1993), which has preoccupied me as I’ve researched the Moorish Science Temple of America. The novel is set in a dystopian future characterized by environmental and economic disaster. In a gated community in Los Angeles, a twelve-year-old black girl, Lauren Olamina, begins to write her own scripture, The Books of the Living. “I’m going to go through my old journals and gather the verses I’ve written into one volume,” she notes. “I’ll use these verses to pry them loose from their rotting past, and maybe push them into saving themselves and building a future that makes sense.” When her home is destroyed and her family murdered, she joins a group of survivors and travels north to start a community where her religion, Earthseed, can thrive.

In reading Parable of the Sower, I wondered about the narrative fashioned by Ali: How many visions of a spiritual community—and of the future—preceded the Moorish Science Temple of America? How often did his followers lament the need for a new god before finding the one that he worshipped? Half a century later, with the bleakness of life for blacks in the United States still definitive, how many times had my parents, hopeful and vulnerable, welcomed an unfamiliar god and flock before embracing Sunni Islam? These questions came to seem impossible to answer by scrutinizing boxes of documents and analyzing theology—or even by coupling archival research with navigating the sprawl of materials on personal websites and social media platforms. Instead, I sought to pay attention to the ways in which people respond to the imposition of history, identity, and belief by inventing their own, and by reinventing themselves.

Olamina, the daughter of a minister, struggles with Christianity, which she feels obligated to practice, even though the Church fails to address the destruction of society, the proliferation of rapes, murders, and arsons. “At least three years ago, my father’s God stopped being my God,” she recounts. “His church stopped being my church.” She regrets allowing her father to baptize her “in all three names of that God who isn’t mine any more.” Then she asserts, “My God has another name.”

1 My research for this essay was made possible by a residency at the New York Public Library; nearly all the historical documents to which I refer are part of the Schomburg Center’s collection.

2 The apparent irony in Ali's choice to employ chapters of these books, all of which were written by white men, is corroborated by Susan Nance's “Mystery of the Moorish Science Temple: Southern Blacks and American Alternative Spirituality in 1920s Chicago” (2002). Nance notes that Ali seems not to have cared who the authors were, since the works were rooted in ancient Egyptian and Indian thought and succinctly articulated a program of self-help, political uplift, and spiritual struggle between the higher and lower selves, which aligned with his teachings.