1

My father, whom everyone inside our house and everyone American outside it called Henry, left China in 1948. I don’t know if he departed from Beijing, where I think he was living, or Fuzhou, where he was born, and I don’t know if he first took a boat to Hong Kong, as my mother would nine months later. Like my father’s English and like most things having to do with his life in China, being Chinese was marked by imperfect chronology and English grammar. My sister, Maya, and I didn’t speak or understand Chinese. We spoke with our parents only in English, and the idea of being Chinese in southeastern Ohio during the 1970s was rendered in English. Every family is the language it finds for itself, and in our family this language, which was really a situation, was attached to our family’s ambiguity and its jokes. Although our family’s words grew less idiosyncratic and I suppose less imperfect over time, my parents’ Chineseness, spoken or otherwise, gave off the impression of things that were not sayable. Or to put the matter more succinctly, life as a Chinese person, at least in Ohio, was vague and incongruous.

In spite of the incongruities, there was not much vagueness actually spoken by my father. He was taciturn and sometimes ill-tempered through most of my adolescence. He disliked most social niceties, particularly small talk at the dinner table. At home, we ate only on dishes my father had made, and until Maya got to high school, the main sound at dinner was the clinking of copper-topped Hangzhou chopsticks against bowls. After Maya got to high school, everything changed: dinners that were short and silent now ended with shouting.

When my father was angry, his English worsened. One evening, a few weeks before Maya left for college, my father turned from my sister, whom he was arguing with, and announced to the table, “You not my daughter.”

My father paused. Everyone kept eating. With the exception of Maya, no one liked to argue with my father.

A few minutes passed. It was hard to tell when he was finished shouting. My father turned to Maya and yelled, “I disown you.”

“You disowned me last week,” she replied. “You can’t disown someone you’ve already disowned.”

Over the years, and mainly while dining, we came to understand what was Chinese in our family and what was less Chinese. Mainly, we knew that my father came from a prominent Chinese family in what he called Foochow, and that his youth had been profligate. From my mother’s perspective, my father had misspent his youth with opera singers whom my sister and I associated with people like Beverly Sills and who my mother assured us were wayward and irresolute.

My father died of a heart attack on August 4, 1989. He received two obituaries, one on August 6, in the Athens Messenger, the paper my mother and father read most of their lives, and another in the Santa Barbara News-Press, in the town where my father had moved to in 1986. The two obituaries informed me of a few things: that my father graduated from Fukien Christian University, a university which he had never mentioned and where he had, apparently, taught and served as secretary to the university’s president in the 1940s. The references to Christianity were unexpected, as my father had told me he had been raised a Buddhist. In the mid-1970s, there were no Buddhists in Athens, Ohio, and my father made no outward show of Buddhism. When I noted this one afternoon while we were working outdoors, my father replied, responding mainly to my mother’s Episcopalianism and the Sunday school that Maya and I attended each weekend, “Buddhism not like that.”

I do not know what my father studied at Fukien Christian University, I do not know how many years he spent there, I do not know whether the university or its buildings exist, or whether it still bears signs of its religion, and I do not know whether his first language was Pekinese or Fukienese. My parents rarely spoke Chinese to each other as my mother’s native tongue was an Amoy dialect along with Shanghainese, and my father’s was a Fukien dialect and Mandarin. My mother spoke or could understand Cantonese, Japanese, English and fragments of French, but not my father’s Fukien dialect. We were thus a multilingual house of loosely related languages, including English, Amoy, Shanghai, French, Fukienese and Peking Mandarin, and unfortunately, no two speakers, except Maya and me, spoke without effort in the same tongue. My parents neither used nor understood idiomatic expressions, and phrases like “kick the bucket” and “hold your tongue” were utterly senseless. My mother sang us lullabies in Chinese, and the first time I heard “Row, Row, Row Your Boat” was in a classroom surrounded by children who, unlike me, clearly understood the song. In relation to feelings, which tend toward the colloquial, my father’s expressions were distinctly un-idiomatic, and those involving affection skewed formal. Once, after looking at Maya’s hair, he noted, disapprovingly, “The hair is long.” After a moment, he added, “Strangely.”

There was never a Chinese speech community in Athens, and my sister and I grew up speaking English and high school French. My parents spoke Chinese only when arguing or talking about money, at home and at the occasional Chinese restaurant, and once, to everyone’s mortification and shame, in Yosemite National Park, during a protracted shouting match on a sidewalk. In front of people other than my sister and me, my parents spoke English. This meant that, as we grew up, my sister and I heard a lot of Chinese, and that Chinese was a species of yelling.

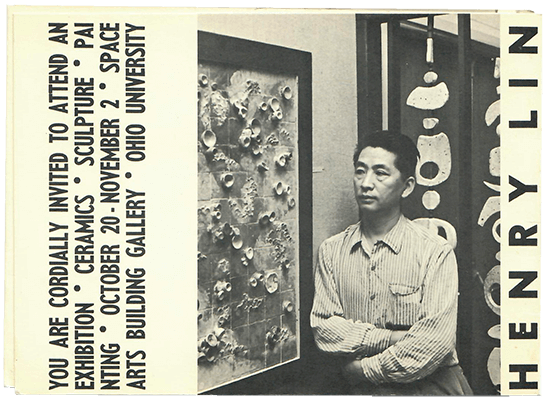

This particular linguistic proposal known as a family was subject to numerous revisions from the late 1960s to the mid-1970s, after the counterculture hit America. Athens became home to a large number of what my father called “ippies,” many of whom happened to be art and frequently ceramics students and Asian language and literature students, and so here the counterculture attached itself, in equal measure, to my mother, who taught what was then called Oriental literature in translation, and my father, who taught ceramics. My sister and I never associated my parents with hipness or hippies, but things about my parents in southeastern Ohio produced an Oriental effect among students. They would drop by our house, impromptu, my mother’s students arriving on bicycles, bearing flowers and almond cookies, and my father’s on motorcycles and in beat-up cars, bearing Raku ware. My mother’s best friend—a woman named Carol Kendall, whom we called Siggy and who was born in Bucyrus, a town I conflated with the middle name of an American president—wrote a book about magical creatures called Minnipins and was married to Paul Murray Kendall, the Shakespearean and biographer of Louis XI of France. For reasons (still) unknown to me, Kendall called Louis “my little spider.”

At one time, I believe in the 1960s, Siggy knocked on our door and announced, “Paul has been nominated for a Pulitzer.” Like my father, Paul and Siggy were Midwesterners who smoked multiple packs per day, and whenever they came over, they brought a Benson and Hedges brick and proceeded to fill the house with smoke. Siggy took up Chinese sometime in the 1970s and would regularly supplement her reel-to-reel lessons with visits to my mother, who was teaching Chinese at the time. At roughly the same moment, Alice, a close friend of my mother’s and a professor of French, left Athens for Taiwan National University to study Chinese, and two years later, Alice returned as a professor of Chinese and French. These two events resulted in more Chinese being spoken in our house by non-native speakers with impure Peking accents. My father was dismissive of the sounds.

One afternoon, Alice came to our house and, using Chinese, dared my father to speak to her in his first language. My father called my mother’s Amoy dialect “not pretty,” and her Mandarin “China from the country,” as opposed to his elevated Peking dialect. My father did not talk much in any language; he particularly disliked English syntax, multisyllabic words, and verbs, and he clearly thought speaking perfect Chinese to an American was less desirable than speaking bad English to anyone else. My father was not polite, but he spoke to my mother’s friend, and his Chinese emerged, as he said, “cloud and lear.” I know of this incident because a few years after my father’s death, Alice informed us that on that afternoon in Ohio, my father, speaking like a vexed politician, uttered the most beautiful Mandarin that she had ever heard.

From reading a biography, I know that my father’s father, Lin Changmin, was an influential political figure in the May Fourth Movement and that he died in 1925, when my father was ten or eleven. My mother told me his mother did not raise him, for reasons she never alluded to, and he was sent at a young age to live with an aunt in Fuzhou. I do not know the year in which this happened, how much time if any he spent with his father, or how much of his life was particular to him and how much was particular to something besides the identity or self by which one presumes to know another person, either living or dead. All I know is that my father in his lifetime never referred to his father, the aunt who raised him, his siblings, or his mother by name. Or to put the matter more directly, the China that my father grew up in is unknown, and the Chinese part of his identity is under-articulated and under construction, which is to say he was always a Chinese person in the making.

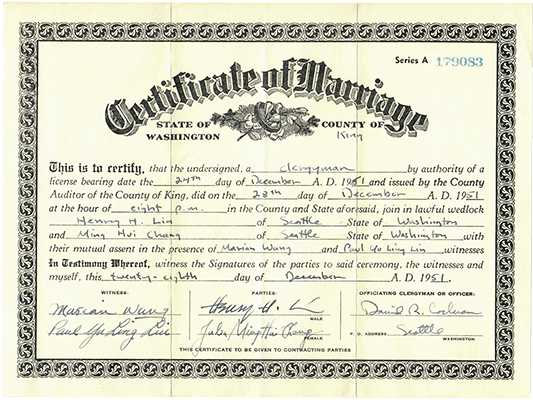

Of his relation to himself, I know little. Of his American life and family, there are names and documents. He married in 1951, early in his American life but late in his Chinese one. He had two children with my mother: my sister Maya in 1959, and me in 1957. He graduated with an MFA in ceramic arts from the University of Washington in 1957 and then taught for a year at the University of Wisconsin in Madison. In 1958 or possibly 1959, he received a phone call asking him to head the ceramics program at Ohio University. Balanced against the story of my father’s adulthood and renaming is a story of childhood in Athens, Ohio. Between 1959, when three of us arrived, and my father’s death, in 1989—that almost generic period in which Maya and I grew up and eventually left Athens, and the language of our childhood became a general household language—my father’s family in China continued to recede. It was not until I got to college that I learned he had more than one brother, and it was not until my mother showed me my father’s family tree in 2011, two years before she died, that I understood he had four siblings. In the months after my mother’s death, it occurred to me that my father had never spoken of the death of his own mother.

At some point, probably in the ’60s or ’70s, when he turned forty or fifty, my father told me that he had come to America a “little too early too late,” by which he meant that a Chinese person in America is an American until she dies, at which point the whole chronological thing, that process wherein a Chinese person is invented in America, starts to run backward, and this reversal, a curious annulment or separation of what life once was, gave my father either two deaths or two arrivals, and possibly both. My mother said that while he was alive, she never knew how old my father was, since he had lied about his age at their first meeting, and no one in our family ever encountered any official documents that corroborated his age or nullified the various birth years he supplied. When we asked him about his birth year, which we did incessantly, my father would say he didn’t know because he was born in a lunar calendar.

In retrospect, speaking mainly for my mother, it appears that at least one of his deaths involved the wedding of things that my father believed were analogous or what he called “related,” and when my father said “related,” he meant “relations” like children or spouses or aunts. But the things that came together after his death were not quite relations and they were not quite the puns my father loved; they were a class of things with a weak classificatory structure and thus were things over which he had little control, like Pabst Blue Ribbon beer and Buddhism, like Japanese roses and southeastern Ohio real estate, like the various gifts exchanged within our family, and in the end like family members as well. And they were moving forward in time by the point I got to them, so any narrative about these things is bound to be faulty and posthumous. The reason for this is simple: the Chinese person who is telling the story, a person who in this case is me, is not dead yet.

Between the late ’50s and the ’70s, the rapidity with which my sister and I became American outpaced the glacial speed at which our parents did, and I came to understand that our collective idea of Americanness, at least in relation to my father and mother, was a moving target, impossible to separate from the fact that our mother had an earlier life in China, one whose chronology was relatively straightforward, and our father did not. The stories about my father’s earlier life were related by my mother, and most were told after his death. There was a time when I believed that my father’s childhood in China was a thing of the past, but as I near the age at which he died, I think I have this backward. The posthumous nature of childhood generally cannot be separated from the blankness of my father’s earlier life, just as the fictional and nonfictional parts of a life cannot be. His Chineseness, like his depression, has come into being long after it has ended, biologically speaking. Childhood, not unlike happiness or its opposite, is one of the ideas formed by a family, and, like happiness, it is imagined late.

2

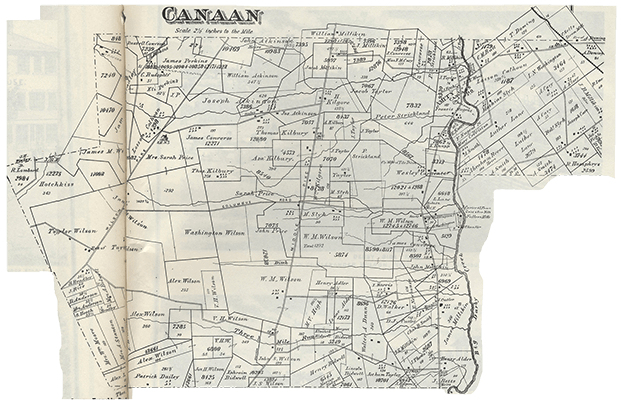

On August 2, 1984, my father bought a seven-acre property in Canaan Township, just east of Athens. The parcel consisted of a small, dark log cabin and, across the road, a Quonset hut. The latter structure was lined with brown fiberboard or Masonite and had an aluminum roof. Our family referred to it simply as the hut. It was, I believe, a warehouse model, and roughly the size of a third of a football field. There were a number of such huts in Athens, sold to small businesses, mainly tractor companies and auto-body shops, and a few families after the end of World War II, when the military divested the huts to civilians, who used them for commercial storage and prefabricated housing. Most of these structures, with their semicircular roofs, were sold for $1,000, less than the cost of a new house.

The hut my father acquired was thirty-four-feet high at its apex and had gigantic pulley-hung doors on either end. It was cool in the summer, when my father would thrust open both doors and a breeze would flow across the concrete floor. It was impossible to heat in the winter. My father told our family that he had bought the hut in order to build a kiln and do raku pieces in three smaller electric kilns. The four kilns were placed in an ellipse dead-center in the hut. The structure was too big for a one-person ceramics studio, but the unfillable massiveness of the space and the open-air ventilation system appealed to my father. It was a building that was not quite a building. Because the hut had its own aerodynamics and weather, being inside it felt as if the outdoors had been enclosed beneath a transparent horizon of a roof. The studio made zero pretense to hobbies or crafts, which my father thought were the bane of fields like ceramics, weaving, and glass blowing in America. As an environmental structure, the hut suggested unlimited aeronautical expansion into the landscape’s horizon. Or to put it in engineering terms, it was the infrastructure of landscape in the form of architecture. The climate of moving air was generated by the heat of the roof in conjunction with the coolness of the concrete. From a practical standpoint, there was a lot of room for hot air to go, in all seasons, and this made the building perfect for kiln firing and lounging around and drinking warm beer. Unlike most suburban structures, it was fully detached, industrial, and working-class. Like a junked Jaguar XKE that spent most of its time on blocks, it looked sporty, unusable, and cheap.

In conjunction with the cabin, the hut generated numerous incongruities of domestic architecture, and disrupted the language of family life by altering its geography. The hut required that my father be away from the house after work and on most weekends. I couldn’t tell if my father bought the hut so he could live alone in a log cabin or if the cabin was a glorified outhouse attached to a workplace. It occurred to me that our family might also be some sort of material instantiation of an idea, an accident concerning the disappointments of family life. In the weeks after he bought the hut, my father forbade everyone except my sister to visit.

My father relented after a few months and, one afternoon, he drove the pickup to the property, and I followed in my mother’s car. He got out as I pulled up. He said nothing. The front door to the cabin was ajar.

“Go in,” my father said.

I had never been inside a log cabin. The differences between the inside and the outside were insignificant: the exterior was composed of molasses-colored logs, as was the inside, a single room. The logs had been waterproofed with a sealant that looked like badly applied makeup. There was one decent chair—my father’s golden recliner, from which he watched TV—and the others were lawn furniture.

There were two small windows, a single floor lamp, and copies of the Athens Messenger and National Geographic on the floor, next to a wood-burning stove. In comparison with the hut, the scale was trivial and the ceilings low. I looked for a fridge.

“It’s dark,” I said.

“The stove doesn’t work. I got a microwave.”

Unlike our own house, which had a large expanse of lawn and furniture that was expensive or that my father had meticulously made from walnut or cherry, the cabin had no lawn and was filled with stuff that I recognized from our basement or from Buckeye Mart, the local discount store where my father bought his power saws, garden trowels, and loppers, as well as a host of gas-powered gear such as lawnmowers and weed whackers. The cabin smelled like smoke. Recidivism had taken hold of domestic life and my father, I thought.

We stood on the narrow front porch, my father drinking a Pabst. There was not much else to do. My father had set up two aluminum lawn chairs, which you could sit on and watch passing cars, but it was unclear why anyone would want to.

My father lit a cigarette.

“What?” I said.

After years of my sister and me begging, my father had quit smoking in the mid-1970s.

“I’ll see you,” my father said.

I got in the car. From the county road that wound around the property, I could see my father go back into the cabin. In the rear view, the cabin, framed by the woods in the background, looked like the one on a bottle of Log Cabin Syrup.

I do not know if my mother saw the cabin or the hut. My mother did not like big, empty, industrial structures, and Maya and I preferred the woods around our house, so this was technically the beginning of the geographic separation of our family. The hut was wide enough to accommodate a few small airplanes, and at this point, in roughly the very late middle of his life, my father began to think about a biplane with a Triumph engine, along with a bulldozer to plow a runway. At dinner, he talked about small-aircraft engines and the flying lessons offered by the avionics department at Ohio University. Although he never bought a plane, as a kind of consolation he bought a blue Chevy pickup and a Jag Mark 2, both of which he parked inside the hut, at its fringes.

Sometimes my father would commute to the hut for a few weeks, coming back promptly at 6:30 for a shower followed by dinner, leaving immediately afterward, and returning around 10; sometimes he would depart for a day or two and not return for dinner; and once, but once only, in the mid-’80s, he left for a period of four months, and did not return for dinner at all, at which point my mother used the word separated to describe what was happening. This was the first and only time she used the word. I was twenty-seven at the time.

My parents’ marriage lasted through this five year period. I have almost no memories of my emotions of the time. When my father retired at the age of sixty-seven or sixty-eight, he told my mother that he wanted to be warmer. He announced that he had put the cabin and the hut on the market, and one afternoon a few months later informed my mother that he had bought a house in Santa Barbara. My mother called to tell me this over the phone, and she cried when she told me the news.

3

One afternoon, in the discontinuous, in-between time between high school and college, my father drove me up the steep hill to the Athens Lunatic Asylum, on a thousand acres of land now called the Ridges. My father parked in front of the main administration building that would be named, some twenty years later, after him. The door was padlocked; most of the other buildings were derelict. The place was more beautiful than I had remembered. It was more park than asylum, with springs, cisterns, stone paths, and overgrown orchards.

“Get the car,” my father said.

This was his way of saying I could drive. I did not have a license, but my father did not consider the asylum roads legal driving roads, just as he did not consider our winding driveway or the dirt roads on our farm subject to vehicular laws. We got in the car, and my father pointed in the general direction he wanted us to go. I took a service road around the back of the complex, past the auditorium, and finally past the tubercular cottage whose front porch had been graffitied over and whose yard was filled with beer bottles.

We drove to a small building with a loading dock. From where we stood, I could look up and see the two upper floors’ boarded windows. A double set of metal doors, reminiscent of a barn door, was wide-open, off the loading bay. It was early spring. It was probably the early ’70s when we walked in.

“Nobody here,” I said.

My father announced, “I’m here.”

Ten minutes later, a man came out of the back and said, “Find what you need.”

It was unclear what was needed or what needed finding. My father was in no hurry. The room was filled with junked Dictaphones, desks, electric pencil sharpeners, and filing cabinets. On one of the shelves, near the floor, next to an adding machine and tape recorders, was a blue IBM Selectric 71 typewriter. Nothing was tagged. My father gestured at the IBM.

The man turned to my father and said, “Twenty dollars,” and my father walked away. Because his English was bad, my father never bargained for anything. Turning his back in the middle of a conversation was part of my father’s Chineseness, and it embarrassed and infuriated Maya and me because we thought it would be taken as a sign of rudeness or of an inability to understand English. Politeness was associated with Americans and not my father; it was a function of language, and thus a problem in language. When speaking with my father, I generally spoke as he did, with the result that most of our conversations were abbreviated and nongrammatical. This manner of speaking was so ingrained in all encounters with my father that I can, to this day, speak my father’s English. Of course what is spoken is not really language, but a particular situation, and this situation is sometimes called real life. My father’s impatience and reticence rendered “Are you going to the store?” unnatural; far simpler to say “You go to store?” or better yet, throw up one’s hands. I motioned to my father to answer the man, but my father simply went to another shelf. It was loaded with bulbous glass lamps. “Lamps, too,” my father said. Neither my father nor the man seemed aware that the other was talking.

Like most of the things my father gave me, the IBM was a gift that did not register as one. It was something that my father thought was necessary. My father had not told me we were going to the Ridges to buy a typewriter. Up until that weekend, I had ridden my bicycle to my father’s office most days after school, after his secretary had left for the day. I would sit in her office, adjacent to his, and type term papers and poems on her Selectric II. After that day at the Ridges, I wrote everything—poems, letters, school papers, college applications—on the blue IBM. I took it with me when I went to college. I acquired a computer halfway through graduate school, I think it was 1984, but I continued to use the typewriter well into the ’90s for the simple reason that I could type much faster with it. I have a few of the round typing balls in a desk drawer. I do not know where the typewriter is.

4

In the weeks following my father’s death, my mother, sister, and I lived together again, in a compressed period of cleaning his Santa Barbara apartment, sorting through the stuff that my father had chosen to make a new life out of in California, and preparing it for sale. Many of my father’s pots had made their way to Santa Barbara; many others remained in Athens, with my mother. My mother typically joined my father in the summers. I never asked either my father or my mother about this arrangement.

One afternoon, near the end of our cleaning, as Maya and I were packing things into boxes, organized roughly by date, my mother pulled something out of a desk drawer.

“Your father was born in the Year of the Rabbit, not the Horse,” my mother announced.

“What is it?” Maya asked.

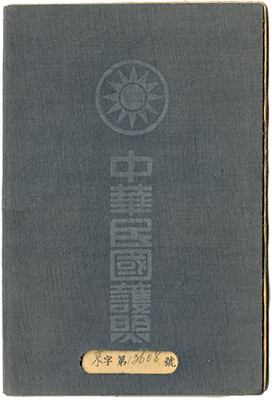

“His passport.”

“What does it mean?” I asked.

“It means that your father told me something different when we got married.”

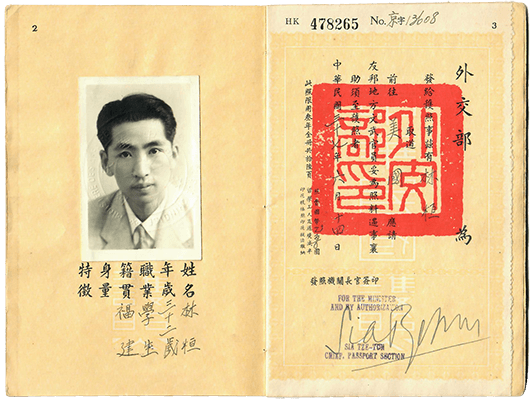

The passport had a blue cloth binding. It was issued on June 14, 1948, to a “Huan Ling,” and it lists August 16 as the date of the immigration visa. A stamp dated “Oct 6 1948” indicates entry to the Port of San Francisco. On page seven, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of China “requests all civil and military authorities of Foreign States to let pass freely M,” after which is handwritten “r. Ling Huang.” The initial passport is valid for three years, until June 13, 1951. On page five, there are spaces for place and date of birth, and these are blank. A blue stamp instructs one to “SEE PAGE 7,” but page seven provides no birth year or birthplace. On page ten, a stamp from the Chinese Consulate General extends the passport to June 13, 1954. In the passport my father has two given names, Huan and Huang, and a surname that does not correspond to the name I think of as my father’s.

When he arrived in the United States, my father was unemployed. His English was terrible. His father, whom he had never spent much time with, was dead, and he had not seen his mother for years. He had a Chinese name, 桓, which was translated as Huan, possibly by an immigration official in Fuzhou, and another name, Henry, which is not in the passport and which, if he did not give it to himself, may have been given to him when he worked as a translator for the U.S. Navy. In Seattle and Athens, everyone called him Henry, even my mother. The relation of Henry to Huan is unclear, phonetically, since the two words do not sound alike. Huan is a tree with white bark and leaves like a willow’s. But huan also means the pillars or tablets placed before a grave and the posts used to steady a coffin when it is lowered into the ground. Everyone in our house pronounced Lin like an American girl’s name. Lin means “forest”; actually it means, calligraphically, one “tree” standing next to another “tree.” There is more than one tree in our name. My father’s death certificate reads “Henry Huan Lin.” Sometimes I wonder what it would mean to name yourself, and then I realize that my father probably did. From the perspective of an American childhood, everything that my father did, especially the American things, had a singular effect: they made him more Chinese.

Among other things, the passport does not tell me that my father’s first job in America was cleaning the toilet bowls and turning out the lights in a large Seattle department store. My mother recounted how she helped him find his way out of the dark department store, holding a flashlight, with my father throwing the switches, and the store going black, first the fragrances section, then handbags, and finally men’s socks and underwear. But mainly, the passport does not tell me at what point in his life, or in what part of the story, I first came to understand that my father would have an American life and a Chinese one, and that the two would not be joined.

My father was a proud, non-talkative, and impatient man, and I cannot imagine him cleaning department-store toilet bowls or turning out department-store lights. For most Americans who are born in America, it is hard to see the arrogance and frustration inside a department store, restaurant, or dry cleaner’s shop because they are so discontinuous and sampled at such slow intervals that they are barely perceptible. I think the store my father worked in must have been either the Bon Marché or Marshall Field’s, because my sister and I are still fond of the mints made by Marshall Field’s. They are called Frango mints and we used to get them every Christmas from relatives in Seattle and now we buy them at Macy’s each Christmas. Bon Marché was probably the only store in the city grand and expensive enough to afford someone just to turn out the lights each night and to have its own brand of chocolate mints. And so for me there is an ineluctably slow connection between a box of mints and my father’s anger, as if a department store could produce frustration as well as resolve and call it a mint, which in turn everyone in our family would fall in love with. Most of what we love is produced by delays in the objects we love.

5

Starting sometime in the ’60s and then all through the ’70s, my parents would throw elaborate dinner parties that necessitated my mother and father’s spending most of the day and the day before preparing food. My father would sometimes order lobster or clams or shark fins from Columbus, and he would occasionally buy a duck a few weeks before, hang it in our basement, and then, a few days before the party, use a thin metal straw to puncture its skin and blow the fatty layer just off the flesh. Although the food varied, the preparation was always Chinese and the dinners were always in winter because my father was a fan of American barbecue in summer. He thought it ridiculous to cook in our house what other people could cook in theirs.

Life, and here I am referring principally to childhood, was marked by the fact that there were no other Chinese people in Athens. Everyone who came to our house from 1959 to 1987, with the exception of my aunt who lived in Dayton and my godmother who worked as a librarian at Claremont College, was American and white. In spite of, or because of, the whiteness, the dinners were notable exercises in how the story of a family is told, for they were the sole occasions when my father spoke about his life in China. And so it was that over a dinner party with non-Chinese people, I first learned of my father’s father’s assassination by the Japanese, the laying out of Tiananmen Square by his half sister, and the blood letters written from prison by his brother, whose plane was shot down over Chengdu in a battle against the Japanese. These stories were vastly entertaining to guests. To members of our household, in particular my mother, the stories were variants of untruth, but to complicate the issue of variability, my father’s lying was neither continuous nor marred by anxiety; the lying, if that’s what it was, was intermittent, accidental, and lacking in heat. But mainly it was, as my father used to say, “related” to Chinese things eaten by non-Chinese people. For this reason, our family’s history is a little careless; it is mainly a series of footnotes to cooking devices like Mongolian hot pots and to Oriental cuisine circa 1970. The lies were simply things we were related to; we overheard them over dinner and so, although lies constituted our family history, nobody in our house felt lied to. Of course, none of my parents’ friends knew how much my father loved American barbecue or Kentucky Fried Chicken.

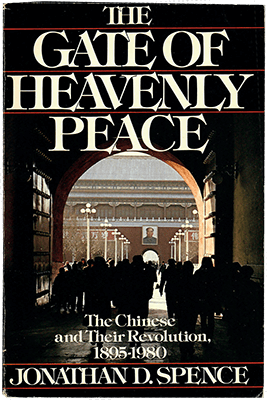

At one dinner party, I learned that my father’s mother was a third wife, or what Westerners sometimes term a concubine, though the word suggests kept women when in fact my grandfather’s second and third wives were considered a natural part of the world order. The story did not upset my mother, and my father was not ashamed to recount it; on the other hand, he never brought it up with me in the many years that followed, and I never asked or wanted him to. By his first wife, my father’s father, Lin Changmin, had no children; by his second, he had one daughter, Lin Huiyin. She was known as a beauty, even in youth; she was nicknamed the Jade Butterfly of Beijing, and the pictures of her that I have are remarkable. By his third wife, he had my father and four other siblings.

Lin Changmin was a politician and writer. Sometime in the ’40s, I believe, he was appointed a senator by Sun Yat-sen in the first provisional parliament. Earlier, as a reformer, he had refused to take the final Imperial Exam, which would have led to chin-shih status. As part of Japan’s “velvet glove” policy in China, which involved taking control of Germany’s leased territory on the southern coast of the Shandong Peninsula, Lin Changmin wrote a number of political articles, including “Shantung Is Finished,” which helped awaken anti-Japanese and pro-Kuomintang sentiment in China, leading to the May Fourth Movement. At one dinner, my father recounted that his father was assassinated by the Japanese in 1925 on his way to a piano concert by Lin Huiyin, and his body was never recovered, but a book on Chinese history remarks only that Lin Changmin “was killed by a stray bullet.”

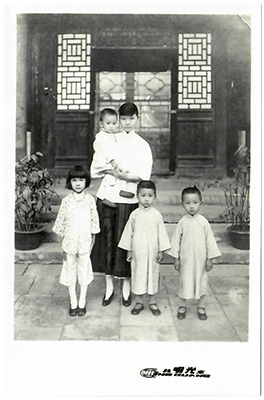

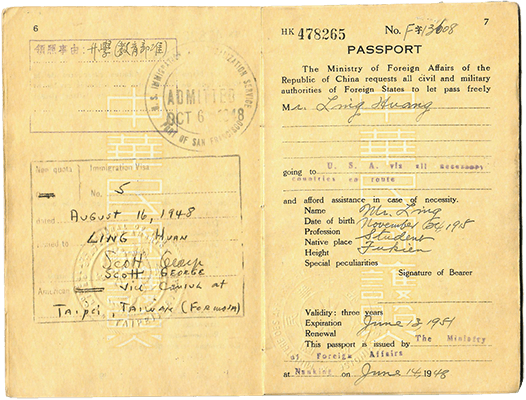

Here are photos of Lin Huiyin at age twenty-seven and my mother at age twenty-four. The former was taken in 1932. When the historian Jonathan Spence was writing a book on cultural life in twentieth-century China, sometime in the early ’80s, he ran into my sister and gave her a picture of Lin Huiyin that would appear in the book, and that photograph was the first image of her I remember. She is standing over an older man with white hair and a small beard, and I can understand even without understanding Lin Huiyin or my grandfather that the picture is of a daughter and father. So much of what I understand about my family is derived from photos that have never been explained to me, and that came into my sight many years after I had heard the stories and formed the emotions that they seem to corroborate and that I now understand are the least reliable forms of reconstructing that thing known as history or truth. Every photo you are seeing in this album is basically a naturalistic lie of one sort or another that my father told. When I came back one December, a few years after my father’s death, to Athens, my mother showed me a picture that had recently been sent to her from China. I don’t know who sent it to her, and I am not sure where it is now. It shows Lin Huiyin and, more important for me, my father, one of the small boys to the left, sitting on the dirt. I am unsure which of the boys is my father.

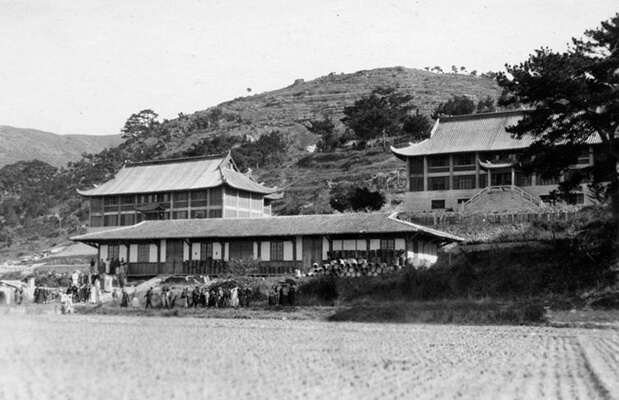

Lin Huiyin traveled with Lin Changmin on many of her father’s foreign visits. She was sent to school in the United States and London, where she became friends with Rabindranath Tagore and G. K. Chesterton. I was later made to understand that my father had, as a child, worshipped her; early photos of my mother are virtually indistinguishable from photos of Lin Huiyin, whom my mother called Phyllis. Lin Huiyin was the subject of much male attention, and Shih Zhimo, who was to become a great lyric poet, fell in love with her and wrote her a now-famous poem, one of whose lines was “My soul searched for you in a sea of eternity.” Lin Changmin would not allow the marriage to Shih Zhimo for reasons I don’t know, and wished her to marry Liang Sicheng. Lin Huiyin and Liang Sicheng married in 1928, the year in which my mother was born, and Lin Huiyin retained her name. She travelled to St. Mary’s College in London and later did graduate work at the University of Pennsylvania. Their careers intermingled. In the early ’30s, they discovered examples of early Chinese architecture, including the Temple of Buddha’s Light, the Temple of Solitary Joy, and the Yingzhou Pagoda. A Pictorial History of Chinese Architecture: A Study of the Development of its Structural System and the Evolution of its Types, cowritten by Liang Sicheng and Lin Huiyin in the ’30s and ’40s, and among the first books to examine timber-frame construction in early Chinese architecture, was published posthumously in 1984. From 1930 to 1937 they took up residence in Beijing at Number 24 Beizongbu Hutong, or what was then called Number 3 North Zongbu Lane, in the Dongcheng district. Lin Huiyin was diagnosed with pneumonia or TB, and in 1937, at the onset of the Sino-Japanese War, the couple abandoned Beijing. After the revolution, she helped design the national emblem for the republic, and with her husband, she was instrumental in laying out Tien-An-Men Square, now called Tiananmen, and helped design the Monument to the People’s Heroes. She is regarded as the first woman architect of China, and her husband the first modern architect, albeit one who espoused a grammar of classical Chinese architecture.

When buildings were being torn down during the Cultural Revolution, Liang and Lin campaigned to preserve Beijing’s architectural legacy and save the city’s inner and outer walls, which had been built in 1435. But in 1951, despite their lobbying, demolition began. Beijing’s opera singers were drafted to dismantle the walls. Within a decade, the outer wall was gone and the inner wall reduced by half. Following the Communist takeover, Liang was condemned as “an authority of counterrevolutionary scholarship.” In 1956 he was forced to self-criticize and recant his advocacy of the traditional architecture of Beijing, considered by party members to be a remnant of a feudal class system. He died three years before the Cultural Revolution ended.

My father told guests that when he left China, in 1948, Lin Huiyin, an ardent nationalist, told him that she would never speak to him again if he left for good. She felt that anyone who left China should bring their skills back to the country they owed everything to. My father never did see her again—she died of TB on April 1, 1955. I was told that Mao came to her funeral and that the name on her tombstone was erased by Red Guards during the Cultural Revolution, but I don’t know whether this is true.

6

My father’s Chineseness was most on display in his refusal to recognize holidays and birthdays. Major holidays like Easter and minor ones like New Year’s Day were treated with equal disregard, and there were a number of years when he simply declined to acknowledge his birthday, whether because birth dates in a lunar calendar were confounding, because in China a person is born at the age of one, or because he didn’t care. Since the holidays did not register as being of any importance, he did not believe in gifts tied to particular occasions, and for most of their married life, my father did not give my mother Valentine’s Day cards, nor did he give her birthday presents. He reserved particular disdain for Christmas, but it was not clear whether it was the gift giving or the religious element that bothered him. The only holiday he seemed to enjoy was Thanksgiving, probably because he could watch Roger Staubach and the Dallas Cowboys with his friend Paul Murray Kendall.

The lack of material or emotional demonstrations of love from my father issued from a fact of my parents’ marriage: by all accounts, my father loved and doted on my mother when he first met her in Seattle. She was beautiful, young, and naive; she had never had a boyfriend, as was not atypical of Chinese girls at the time, and her father had arranged a marriage for her with a man who my mother told me was named “Fred” and who was scheduled to arrive in the United States in early 1949. I know little of this arranged marriage and even less of my parents’ courtship, but my mother once told me that she had thought my father was a good cook and that his gene pool was promising. As far as I have been able to piece together the history of my mother and father’s relationship, she did not return his love in the way that he desired, and this was for many reasons, some owing to his ill temper and arrogance, some to her youth, and some to my mother’s feeling that she had betrayed her father, who sent a telegram to my mother in which he forbade her to marry my father and refused to give her away. Neither of my parents ever complained about the marriage, and the topic of divorce never came up. Here my parents were equally Chinese: to complain about things as they were not would have been a pointless exercise. Desires did not exist to be gratified. Maya and I learned that love wasn’t about expressing emotions; it was what made expressing emotions unnecessary.

My father’s attitude toward gift giving had two effects: for Maya and me, the idea of romantic love between parents was a ridiculous American concept that resembled the relationship between the millionaire and his wife on Gilligan’s Island. More importantly, each Christmas and birthday was a time of great turmoil, for it would invariably be our mother who would take the car (she hated to drive) and get presents while telling us that our father liked to spoil holidays for everybody. My sister and I waited with extraordinary dread and excitement for something, anything. I realize now that we were waiting for a wish, really some sort of obscure desire that would issue from my father, something that was half about the pleasure of receiving something that, coming from my mother’s frustration and her love, would be extravagant in quantity, and half about something that would be fulfilled by being removed from us at the moment it was given. But perhaps my father understood that most gifts are unequal to the emotions they make possible in people and that most objects, like gifts and perhaps people as well, are mainly obstacles to desire. What, after all, can we do with our father’s missing presents except to find them again, like a missing relative or a devotional object, and to catalog them in the years of a later happiness?

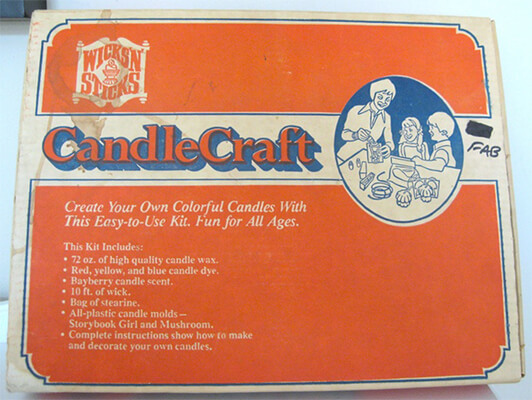

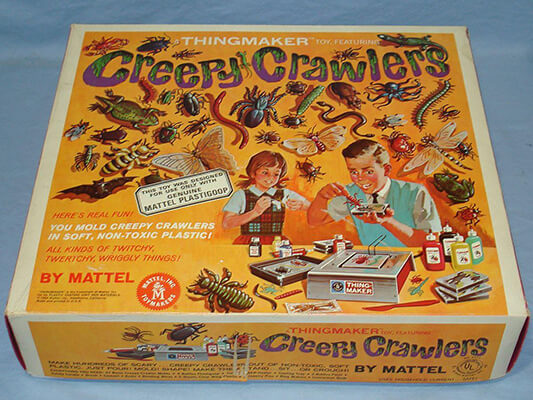

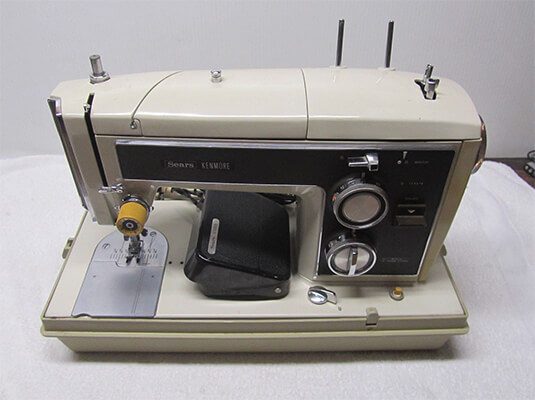

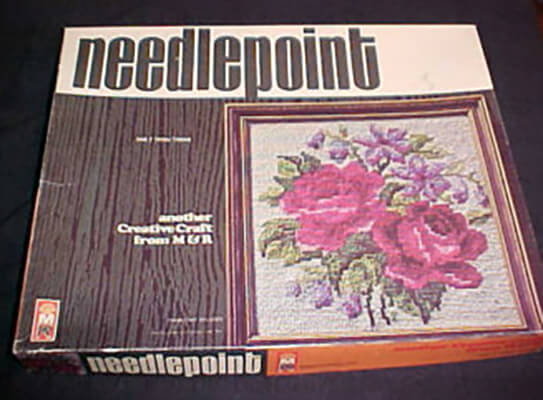

When my father moved out of our childhood home, he took almost everything that mattered to him to Santa Barbara. For reasons that are unclear, many of our childhood belongings went to California. In the process of packing up his apartment after his death, I found two boxes containing things mostly from grade school and high school, packed in no particular order, suggesting that the past is an inventory of unclassifiable things, that the logic of a gift is not strictly chronological, and that what separates an object from a desire is an incongruity we call earliness. Over the course of a morning, we cataloged the objects and photographed them. Maya laid her gifts on a Scandinavian rya rug that she had made in high school: a table loom with what looks like a partly unraveled napkin on it, a Sears sewing machine, a bronze-casting kit, knitting needles, candle-making kits, needlepoint kits, embroidery kits, a rya rug-making kit, an electric hot plate for melting wax, a stuffed-animal-making kit, a complete set of the Time Life Plants and Animals of the World, a Creepy Crawlers kit, a box of pastels, and my father’s drafting tools. The earliest gift was the Creepy Crawlers kit, which I think she got when my mother took Maya and me to Seattle, in 1965, to finish her dissertation while my father stayed in Athens to oversee the renovation of our house. The last gift was the set of drafting instruments that my father used when he was in school.

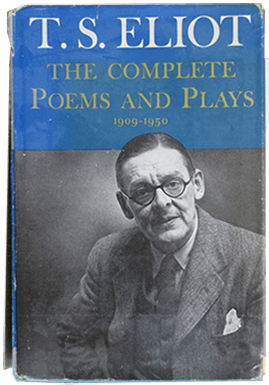

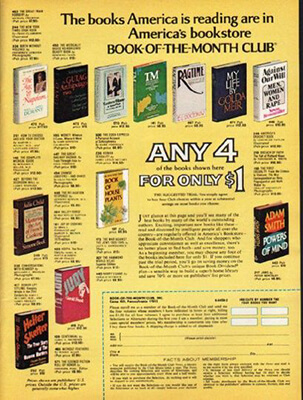

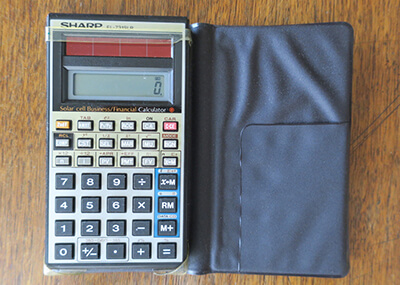

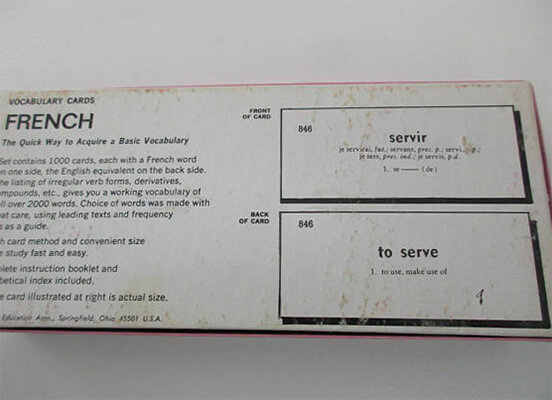

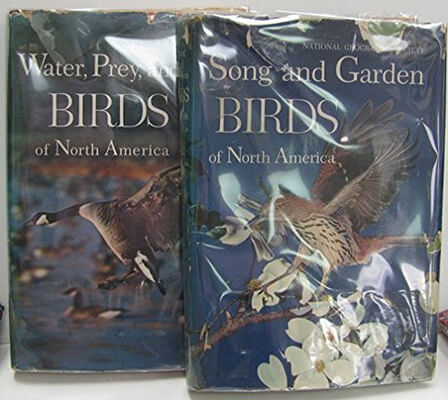

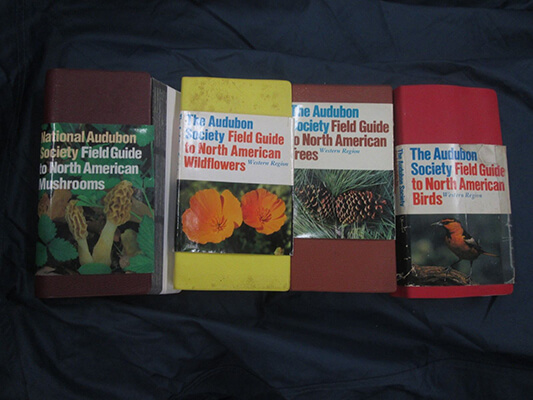

The gifts given to me were laid out on the dining room table that we ate our family meals on. They date from roughly the same time as Maya’s, perhaps a little earlier. The inventory lists a portable Japanese Go set, a membership to Dr. Seuss’s Reading Club, the collected poems of T. S. Eliot, a Dymo label maker, a Parker pen, a two-volume micrographically reduced version of the Oxford English Dictionary, a membership to the Reader’s Subscription book club, a Cross mechanical-pencil and pen set (now lost), a set of black golf club covers with red numerals, a book entitled Fortran IV and the IBM 360, a Mont Blanc fountain pen, a Dansk candle holder, the collected poems of James Wright, Robert Bly’s Silence in the Snowy Fields (for my fifteenth birthday), Scott’s Standard Catalogue of US Postage Stamps in two volumes, a membership to the Book of the Month Club, a Japanese stapler, The Gammage Cup by Carol Kendall, a Timex with glow-in-the-dark hands, a ceramic letter opener, my father’s only set of cufflinks, a small engraved wooden ball, a Chinese gong, a small blue and gold Futura 382-07 vase, an electric ice-cream maker, several portable radios, a Sharp Business/Financial calculator, the two-volume, slip-cased National Geographic Society’s Water, Prey and Game Birds of North America and Song and Garden Birds of North America (second grade), later supplemented with the National Audubon Society’s field and tree guides to the eastern United States, a Chinese jewelry box, a small pair of binoculars, a Tiffany T pen that my mother had inscribed with my name, a Van Briggle footed bowl, a professional badminton set with French feather shuttlecocks and a tournament-standard net, and a box of French flash cards. These things remind me not of the persistence of things but of the irretrievability of the past and all those things that are absent: a blue filing cabinet that held the poems I wrote in high school, an IBM Selectric, and my first desk, which my father made for me out of recycled kitchen cabinets.

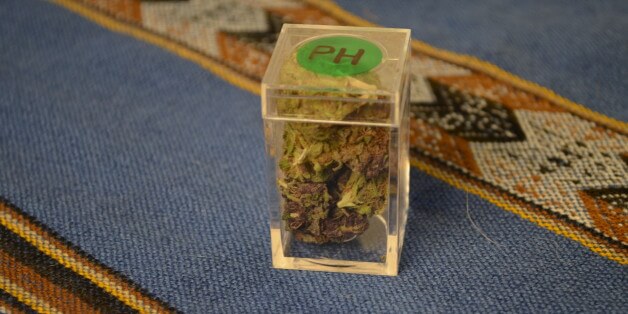

When I was fourteen or fifteen, I painted my room blue, and throughout high school, I spent most of my free hours alone in the room, which had two windows looking on to the woods that bordered our house, listening to music, reading James Wright and Mark Strand, smoking weed, and writing poems on the IBM Selectric. One of the first albums I bought was R.I.P. by Steppenwolf from the Columbia Record Club. It arrived in the mail, packed in a cardboard sleeve, and I played that album countless afternoons while smoking in my bedroom. I kept my stash and Bambu rolling papers in a transparent yellow plastic box, next to my fountain pens in a desk drawer. One afternoon my mother knocked at the door and asked what smelled and I replied that it was incense, after which point I never had to worry about smoking in my room.

Most of the gifts in these photographs came from a moment when it was mainly other people who bought things for us, in this case my mother, and the photographs tell me that a family’s happiness lies mostly in things a person cannot find for herself, and that individual desires take a long time to reach the person or things they are seeking. Like a lot of things from the past, the gifts are still receding from the present, into the space of recollection, alongside desires that seem gratified or not, either in the present or in later life. Anyone who has desired anything can tell you that a desire without an object in its way wouldn’t be a desire at all. And the most beautiful desires are always inventories of the unfinished portions of a life. The photographs are awkwardly social, spreading out or sequestered in a time or a room that is not quite the present, and whose subject is a family not exactly our own, though to an outsider it may simply look like a color photo found at a flea market or edited in Photoshop.

Life is the sum of things that end and life is also the sum of things that prevent one from coming to an ending, and the attempt to find my father, like the attempt to give his life a form, is subject to limits that are not strictly temporal in nature. The objects in these photographs, like the period of my adolescence and his adulthood, are merely parts or relations of some other thing. In this sense the objects never imitate anything but life itself, and they do so with relentless imprecision, reproducing people as books and objects as humans all the time, confusing beards with hemlock trees, aunts with TV sets, and children with (in the 1970s and ’80s) Dairy Queens, Hall & Oates, portable radios, coal mines in Nelsonville, pieces of pottery, Broadway musicals, gene synthesizers, audience analyzers, and Gilligan’s Island. In the end, whatever that may be, the earliness of the photograph tells me that in regard to the dated things in a photograph, the past is weak, descriptively speaking, and that the ineffable is that point when our descriptions stop describing the things we are feeling. And yet all of these objects are the more or less true history of our family. Everything in these photos could be said to exist, and their existence confers order to something that remains to be ordered. My father never intended to be a potter and he never intended to move from Fuzhou to Ohio in 1957, when I was one and my sister was not yet born. His life, like the various items in a photograph, was an ending without much of an ending or a teleology without much that is teleological. Of course, the institution of marriage and family, like a scrapbook such as this one, makes it unnecessary for any individual person to love anything in particular or to remember the details of a life, though I suppose that, whereas institutions used to do most of our collective remembering, it is now mostly the internet that does so.

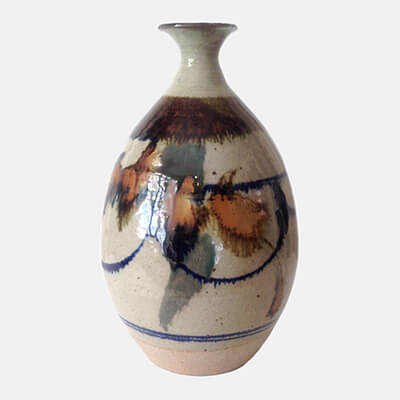

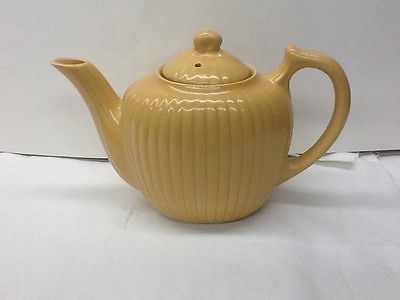

Once or twice a year, I search for my father on the internet. In April, I found a ceramic bowl, glazed in slightly greenish brown tones. One photo showed his signature in Chinese, the calligraphic symbol for two trees. The listing included a photo of my father with Virginia Weisel and Robert Sperry, two potters associated with the Northwest Designers Craftsmen, a pottery movement in the Pacific Northwest of which my father was a founding member. Sperry and Weisel were, I believe, acquaintances of my father’s. Sperry died in 1998. A search for Weisel turned up nothing, and I don’t know if she is living. Like most of my father’s small pieces, particularly the bowls and plates that we ate our dinners on, and like the idea of domesticity itself, the piece is undated. While we were growing up, my father was adamant that we not eat on any commercial, store-bought, slip-poured pottery, and so there was none of it in our house, with the exception of a set of white Centura dinnerware, which my father considered a form of glass and not ceramics and thus OK to have in the house, and a fine china set by Lenox, which had been given to my parents as a wedding gift. It was not until after my father passed away that my mother and I began collecting vast amounts of commercial, slip-formed stoneware, everything from candlesticks, vases, covered bowls, planters, coffee and tea services, and full dinner sets. Most of these were acquired in antique malls in Nelsonville, Logan, and Columbus between 1989 and 2004, and they were mostly produced by American crockery firms, like Hall, Hull, McCoy, Weller, Shawnee, and Rookwood, that had been drawn to the Ohio River valley, which my father termed the “clay corridor.” A few years after my father died, I found in a thrift store what is now, besides a coal black teapot that my father made, one of my favorite teapots, made by the Fraunfelter China Company.

Now that I’m approaching the age at which my father died, I believe that everyone waits for a dead relative to become an individual in some mental version of the afterlife. But that is not what happens. People like my father become less individual with the passage of time. And that is probably why, when trying to track dead people on the web, especially recent immigrants, or looking at gifts from childhood, one remembers waiting for a few things loved by someone else, as if people could be caught in a series of procedures that replace memory with algorithms or dates connected by hyphens in a search string. The photos of the objects, most of them gifts exchanged within our family, are like that. A family does not conclude in an object; a family is a disappearing medium with a few objects that someone left inside it. My father’s obituary, like the future, or like a version of earliness, passes through some of these things, none of which is death, and this death, which is not exactly his, leaves traces in the objects left by it. So there is no real distinction between my father’s existence and his nonexistence. There are fourteen items arrayed on a carpet and thirty-five on a dining room table. I sometimes mistake them for a very late or very early death.

7

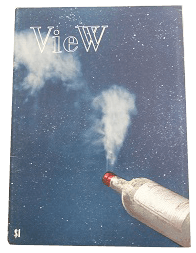

In the year before he died of a heart attack, when my father was living in Southern California, we would often go to a flea market at the Rose Bowl in Pasadena to look for used furniture, camera equipment, and knickknacks. On one of our last trips, sometime late in 1988 or in 1989, my father and I met a man whom my father would continue to converse with, mainly via letters but occasionally phone calls, until he died, and whom he referred to as “the Egyptian,” and occasionally the Pharaoh. When we first saw him, he was smoking cigarettes and chatting in someone’s booth. I thought at first that he was Chinese, because he looked like my father, although he was dressed as an Indian and wore a turban, with loose white pants that resembled pajamas and an embroidered white buttonless shirt. He was wearing some sort of cinnamon perfume and appeared to have had more than one life. When we passed the booth, he acted as if he were surprised to see us. He asked us to sit down and have tea, and proceeded to tell us that he made ointments to sell to people with chronic skin problems, especially in places like Hollywood, where people worked in the movies under lots of light and tended to think their skin was bad. There were a few creamy-white glass jars of his product on the table, placed next to a copy of View Magazine, which I bought that day, and some Futura vases and Van Briggle bowls, a balsa-wood gift pack of English Leather (unopened), and a few Dansk candleholders and teak items, which I also bought. In fact, I bought almost everything he had on his tables that day.

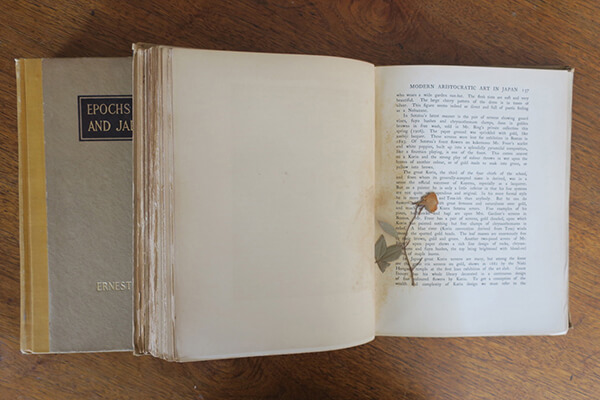

On a small bookshelf next to the table on which we were served tea, I saw a copy of Epochs of Chinese and Japanese Art, by Ernest Fenollosa. This set of two books was mustard colored, and when I saw the books I remembered them. They had brown labels stamped with bright gilt letters on the covers and were published by Frederick Stokes Company in New York. I picked them up. The board extremities were rubbed and worn. There was foxing to the pages. The paper of the front and rear hinges in the second volume was torn. No date was listed anywhere inside, and I presumed the books to be the 1913 American edition, printed with sheets sent from England. When my father saw me holding the books, he said he had given them to my mother shortly after they met, in August 1956, and I recognized the lightly stained boards from seeing them in my mother’s study in Athens. The Egyptian said to me, “You can have them for twenty dollars.” My father did not say anything to me, which indicated, I think, his general approval. It was the unstated thought of both of us that the books were far more valuable than what was being asked.

I said, not quite speaking to anyone in particular, “The books mean something to us.”

The Egyptian shook his head. He carefully wrapped each volume in white paper and secured each package with a small amount of scotch tape. I was indescribably happy to have found the paired books; they seemed like a gift that had come from inside the world. A family gives itself gifts over and over again. Here was a gift that doubled, in time.

When I visited my mother in Athens, a few months later, I leafed through her copy and found a rose, pressed between pages 136 and 137; the rose, preserved by its own vague outlines of a scent, had left a green and red dust cloud on the pages. If not for this, I think the editions were exactly the same. The two copies of the Epochs, one in my mother’s study and one in my New York apartment, together suggest two distinct trajectories of a family’s life. The books have saved something of my mother and father’s relationship that my parents themselves had not been able to.

After the books had been wrapped in paper, the Egyptian smiled and motioned to items on the table. My father looked at a rubbed-leather case filled with lens filters and a Rolleiflex light meter. He told me, “I have that set of lens filters in a box in Athens.”

The Egyptian, who wore dark red nail polish, said to my father, “You are Chinese, and you are yellow, and you are a photographer.” He announced this matter-of-factly, as if it were known to everyone in the booth. A few customers stared at us. Then the Egyptian told us that his name was LordPharaoh ImHoptepAmonRa. He asked my father his name, and my father replied, as he always did, “Henry Lin.”

Over tea, the Egyptian told us about his ointment, which he referred to as “my salve” (he pronounced it “saaav-uh”). I opened a bottle, and inside was a thick yellow sweet-scented unguent. It was designed for rashes and sunburns but was also useful for scar tissue, a problem that my father had after his first coronary bypass, which, because it involved removing a vein from his leg and inserting it near his heart, created a scar that ran from his thigh to his ankle and that caused my father undue itching and pain. The Egyptian gave my father a jar, around which he wrapped a small piece of paper, secured with a rubber band. A few weeks later my father would buy a jar by mail order (a small jar cost twenty-eight dollars) and have another shipped to him in Santa Barbara once a month. Mr. LordPharaoh ImHoptepAmonRa said that the name he had given us was not his birth name. It was two names he had found fortuitously and put together. He told us he had been born Westley Howard. He added, “That is a boring name, but there was no shame in such a name. It was who I was.” He worked as a water-filter salesman in Chicago in the ’80s. One day he was in a diner when a man approached him, confessing that he had a secret and that he wanted to pass it on. Mr. Howard was not surprised by such a gesture. “I’m a spiritual person, so these things happen to me all the time.” The mysterious stranger gave only his last name, Imas, and announced that he was a doctor, though where he practiced, where he lived, and what his specialty were remained mysteries in more than two decades of meetings and exchanges; Dr. Imas never bothered to complete the story for Mr. Howard, and Mr. Howard never bothered to ask for the details.

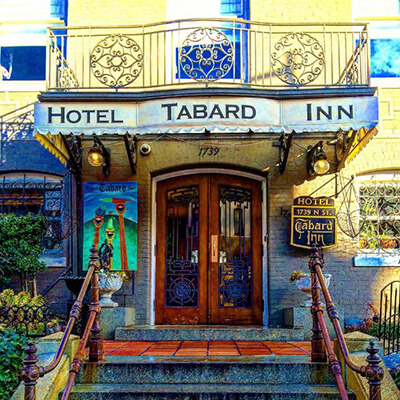

Dr. Imas would periodically phone Mr. Howard in Washington, DC, to arrange a meeting, and at these various meetings, always held at the Tabard Inn off Dupont Circle, Dr. Imas slowly and for no discernible reason taught him, step by step, though in no particular order, how to make what he called “the ancient unguent,” a concoction of olive oil, beeswax, bee pollen, royal jelly, and propolis, the substance that bees secrete in order to seal their hives from the rain. Because the recipe was completed over many years, with gradual, various, and often quite minor additions, its teaching overlapped with a number of American presidents, from Jimmy Carter to Bill Clinton, and spanned the entire term of Ronald Reagan. The arrival of the ointment in the mail reminded me of the American presidency, or of the undulating core of a lava lamp, which is to say that the jars had the effect of a TV sitcom or the evening news sealed inside a jar. The ointment that my father used, the Reagan cream, is coupled with my father’s first, and nonlethal, heart attack; his love of newspapers, especially the classified ads; and, of course, the president at the time immediately preceding his heart attack, whom my father referred to as Mr. Reagan and whom I associate with (posthumous) forgetting.

Why the Egyptian bothered to tell us his history, I and my father were never able to figure out, but I suspected it had little to do with the claims he made for his magical ointment. He spoke an impeccable English; his identity, whatever it was, seemed to issue from a world that communicated solely by word of mouth, without recourse to advertising. And sure enough, as the Egyptian would soon tell us, celebrities started gravitating to the stuff when it got out in places like Los Angeles and Aspen. Madonna bought jars and jars and gave them away. Sarah Polley, Michelle Williams, Emily Blunt, Kate Hudson, and Virginia Madsen carried it around with them in their huge handbags. Bill Clinton, lounging by the fireplace at the Tabard Inn, ordered a case for Chelsea, who was living in Boston, and who reputedly gave jars away to her bridal party. Barack Obama was given a box by Michelle just after the 2008 Democratic National Convention; John McCain received a box, anonymously, from Cindy. These were all documented in a story on unexpected campaign gifts in Politico.

Every time my father needed another jar, he would take out his pen and write a letter to Mr. LordPharaoh ImHoptepAmonRa. Invariably, a few weeks after the order had arrived, my father would receive a second small packet from “The Egyptian,” usually bearing a few photos. One time it included a photo of “my wife Vanessa,” another time some Fotomat photos of his daughters, and once, in a small glassine envelope, was a photo of a young woman in a belly-dancing outfit. Penciled on the outside of the envelope was “my girlfriend Erika.” The Egyptian never wrote on stationery, just on the backs of envelopes or on postcards from hotels. On one of his postcards, he told my father that Egyptian Magic would always be a mom-and-pop sort of store in a jar and that he would never sell his company secret to a multinational conglomerate and that this was all befitting the balm that Alexander the Great was preserved in after his death.

The Egyptian was the most polite man I or my father ever met, and his politeness suggested that he had at least two selves, both of which seemed endless: the one he appeared to be in public and the one he was before taking on another name. It was this split between such indiscernible personality traits that made him resemble who he was—and probably, as my father insisted, Ronald Reagan too. And so in a way he came to resemble my father, who also was not so much a self composed of dutiful opposites as an ointment of objects, many of which were minor or boring or vivid or perfumed or dying, and yet they were all a kind of glacial salve for the unpleasantness of life that makes life resistant to repetition. Politeness was a salve that took the form of a repetition for the Egyptian, and politeness was the bit of mortality that my father lacked, which I suppose is why he and the Egyptian became such good friends and took such pleasure in each other’s company, for it was the Egyptian’s politeness that always triggered enjoyment in my father and in the subsequent memories I have of the two of them. And so in the middle of what was probably my father’s depression, from his late sixties to his death, I was always surprised and then a few moments later I would be surprised again to see the Egyptian in a café or natural-foods store with his Louis Vuitton bag and his fingernails painted a brackish red. And when my father and I would run into him in a café on one of the Pharaoh’s frequent trips to Santa Barbara, or when my father and I would look at his photographs and guffaw to each other at night, sitting in my father’s apartment in Santa Barbara while watching TV, one of us would fall asleep, and on awakening, the other one, usually my father, would say: “The Pharaoh is talking like Ronald Reagan.” And we would laugh and laugh for no reason.

I did not understand this beautiful laughter then, or how the medium of love functioned as a kind of historical omission in the life of a family like ours. Of course love is just one of the many general mediums in which a family’s history and its memories take place. I pick up the photo of the gifts on a table and they are participating in a moment that will come much later. In a family, a photograph is a general, highly obsessive thing that makes no distinction between what is a family and what is not, and between what is living and what is not. In a family, love is mostly something you forget in order to remember at some later point. And as anyone who has fallen in love can tell you, love is the best medium for forgetting the many things in the world that do not need remembering.