1.

I was in my early twenties when my aunt handed me a VHS cassette with my mother’s name written on the label. My aunt and mom worked at a school for hearing-impaired children in Oslo, Norway, and at some point in the 1980s the school introduced video technology as a training aid for sign-language teachers. Unbeknownst to my family, my mother had sat for a recording session. Many years later, while cleaning out a storage room, a coworker who must have known my mom came across the cassette, which was then presented to my aunt and in turn given to me.

The video is a little over nine minutes long and consists of two scenes of roughly the same duration. In both sequences my mother is seen from the waist up, seated before a curtain, translating recorded speech into sign language. In the first scene she interprets several male voices, acting out a fairy tale about a bear, a fox, and a man named Knut. In the second scene she translates a female voice, which narrates what seems to be the story of a girl named Nora, but here the sound is muffled and barely audible. My mother mouths the words, emitting faint whispers. When I was younger I probably could have understood what she was saying in the video solely by way of her signing, since I spent some years attending a nursery school for deaf children. This arrangement—unusual for a hearing kid—came about for practical reasons, as the nursery school was connected to my mother’s workplace. I picked up sign language without effort, but forgot it just as easily after I was transferred to a regular kindergarten.

My mother is dressed differently in the last scene of the video, which must have been taped on a separate occasion. Her first outfit is a yellow-white blouse, while the second is a blue button-down shirt with a reddish scarf. (Since the image quality has deteriorated, I can’t identify the colors exactly.) Between the two takes there is a short close-up of her face, lasting only a second, shot seemingly by accident from an alternate angle. I find this frame, in which she is caught off-guard, to be the most captivating moment in the video. She looks beautiful.

On January 8, 1987, my mother died. I don’t know when she received the diagnosis of breast cancer, or at what point she knew that there was no longer any hope of surviving the disease. Although I was, at least toward the end, aware that she was severely ill, I don’t think anyone told me straight out that she was about to die. In any case, I wouldn’t have been able to fully grasp the concept of death.

I was six and a half years old (when the “and a half” feels important) when it happened, and just entering the stage of development when childhood amnesia kicks in and washes away earlier memories. This would explain why my recollection of my mother is so vague. Bits and pieces have stayed with me and been cultivated, probably even falsified. But my real memory (my real “self”?) only came into being on that January evening in 1987, which I can still account for in detail. Most vividly, I remember the reactions of the grown-ups around me in the following days and weeks, their public displays of grief, which exposed for the first time a vulnerability that is normally hidden from children. I mourned, but my mourning was of a more quiet kind. While I do remember the pieces of music that were played at the funeral, and can get tearful when I hear them almost three decades later, I can’t tell for sure if I cried when we buried her.

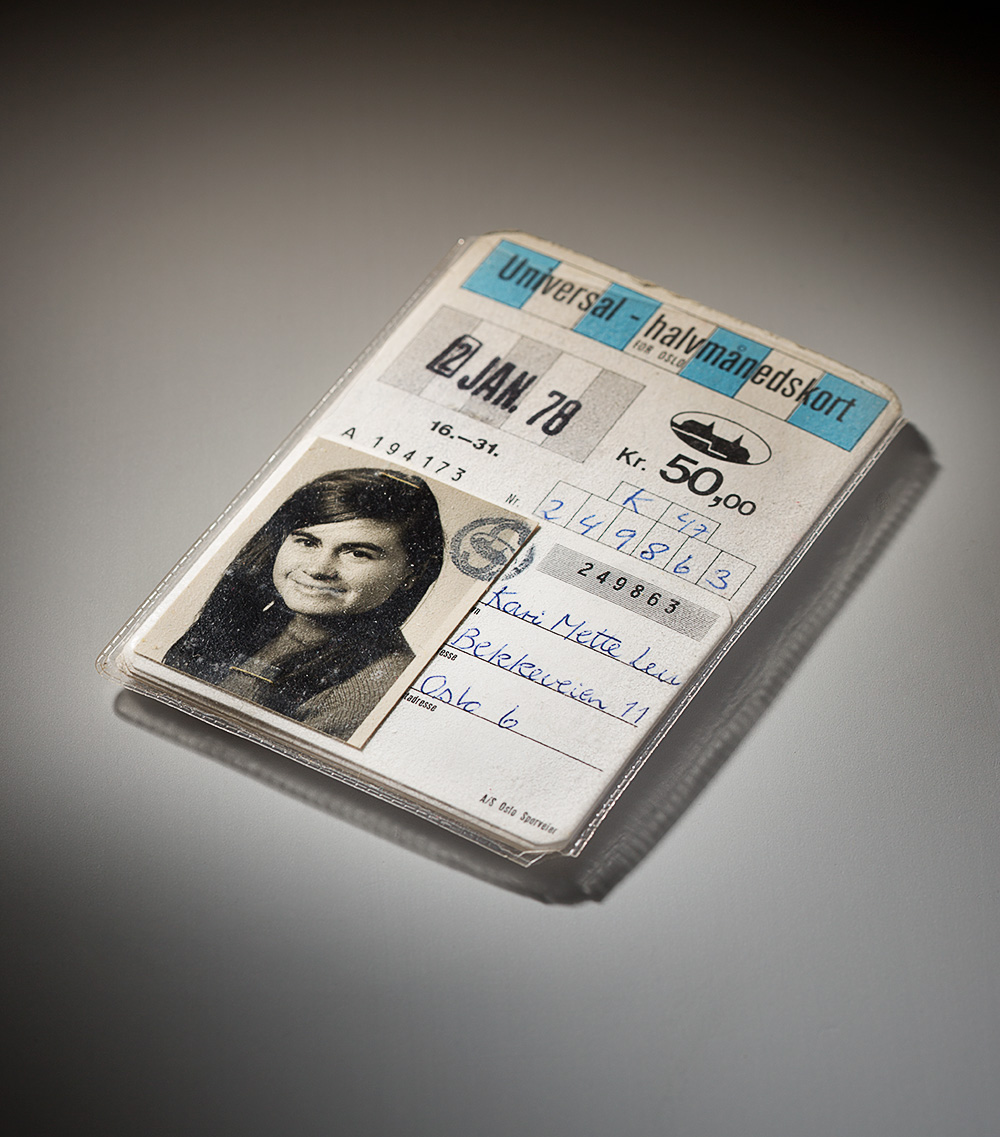

I’d need a therapist to assess how successful I’ve been at processing the loss and evaluate how the death of my mother has affected my personality. By and large, I think I’ve managed OK, and I quickly bounced back, as kids tend to do. I missed my mom, but as time moved on my longing for specific characteristics, like the sound of her voice, was replaced by a more abstract feeling that something, rather than someone was missing. And concurrent with my transformation (I could even say canonization) of her from an individual into a symbol, I found myself increasingly attached to the physical objects or “worldly possessions” that she left behind.

Certain items I held in high regard long before she died, like her dark brown, faux-fur coat, a source of fascination for me and my sister. We treated it as a big, cuddly toy, and named it Burre, after the rodent protagonist in one of our books. Since Burre, my mother’s coat, was already person-like in his own right (and gendered male, like his namesake), it’s understandable that he would remain dear to us. I believe that clothing has always been among the most prized forms of memorabilia, and for obvious reasons: We express individuality through our clothes; they constitute the self-styled, outward image of ourselves. Like a skin, they match our corporeal proportions. Like a shell, they usually outlast the wearer. But more importantly, clothing can provide a tangible bond to people who are gone, as their closeness to the wearer guarantees an authenticity superior to that of most other personal effects. Why else would a shirt Michael Jackson wore during a 1984 concert, when auctioned in 2009, command nearly four times the price realized for the piece of paper bearing Jackson’s handwritten lyrics to “Bad”? (Lot 837 at the same auction, Marilyn Monroe’s white terry-cloth robe—purportedly the last garment she wore before dying—sold for a staggering $120,000, more than double the winning bid for Jackson’s shirt.)

Perhaps my devotion to Burre can be connected not only to Jackson’s stage costume and Monroe’s lounging apparel but to the coveted seamless tunic of Jesus. According to the Bible, the band of Roman soldiers who crucified Jesus kept his robe. Today three competing Christian traditions claim to possess it. Pilgrims can visit robes in Trier, Germany; Argenteuil, France; or at shrines displaying fragments in Russia and Georgia, as the Eastern Orthodox Church asserts that the sacred fabric was divided into several smaller portions and then dispersed. Even if Jesus did walk the earth, and the tale in the Bible is true, it’s tempting to smile condescendingly at the believers, for at best one-third of them are worshipping the genuine article. The rest, even the most pious will agree, are praying to an old rag, the product of a scheme born from fraudulent medieval relics. But as my own experience attests, the irrational obsession with mementos is not confined to ardent followers of Christianity or any other faith. Determined to keep a fading memory alive, I began guarding the traces of my invisible mother religiously. It soon got complicated.

2.

I was eight when my dad decided to sell the house where I was born. To me, the move was nothing short of expulsion from Paradise. If my mother was now a saintly figure, that house was her temple. For us to leave was sacrilege. Later, I became deeply upset when my dad announced that he was going to scrap the car, which was peculiar because, as opposed to the house, the Soviet-made Lada was only the latest in a succession of family vehicles, and I don’t think my mother had even used it very much. I was actually a little embarrassed of the car, as the Lada had a bad reputation in those days. Yet I venerated the Lada and, oblivious to the cost of automobiles, I began fundraising to save it from the junkyard—“begging” is probably a more accurate word. I made a piggy bank out of a cardboard box and asked for donations to “rescue the car” whenever adults stopped by our home. Needless to say, I had a difficult time rallying support for my cause.

The incident when I most fiercely—and absurdly—guarded the traces of my mother involved telecommunications. In Norway in the 1980s, a state company held a monopoly, meaning that customers didn’t own their telephones but leased them as part of a subscription plan. Anyone wanting to upgrade to a newer model needed to hand in the old phone, as my father did when the rotary system was supplanted by push-button technology. It’s hard to tell why the idea of losing this object felt especially painful, but I remember crying my eyes out on the drive to the phone store in a mixture of anger and despair, pleading with my dad to change his mind. Perhaps I pictured her talking and breathing into the phone for so many hours and imagined that her spirit still resided in the plastic box. I can only speculate. But I can say with conviction that my mother’s death produced a hoarder. Ever since, I have dreaded (and I really mean dreaded) the necessity of throwing things away.

3.

The Internet has proved helpful in legitimizing my behavior. Sites like eBay have shown that there is a market for even the most obscure paraphernalia. The 2016 craze for Walt Disney VHS tapes from the so-called Black Diamond edition is an extreme example: Overnight, 1980s and ’90s video releases of Disney’s animated films were alchemized from thrift-store refuse into eBay gold and listed not for hundreds but thousands of dollars. I’ve never had any Black Diamonds, but I’ve seen an old pair of sneakers sell for 350 dollars and a vintage skateboard fetch twice that amount, which is welcome affirmation that I made the right decision in holding on to so much stuff that was at one point considered worthless. Ironically, the knowledge of these dramatic increases in value makes me all the more reluctant to part with things from my, well, let’s say “collection.” What if their value continues to escalate? Won’t I be twice the fool? There have been occasions on which I have sold off inventory in order to make an extra buck, and I’ve always wound up regretting it, regardless of the financial outcome. The Ibsen quote is true: “Only the lost is eternally owned.” What I’ve sold is what I most often reminisce about. (Yes, I’m thinking of you, multipurpose-flashlight-turned-over-for-cash-to-a-classmate-in-fourth-grade.)

Being a keen gatherer of memories as well as things, I was disturbed to hear the nuts and bolts of recollection explained on a popular-science radio show. Apparently, when retrieving an event from the vault of the mind, the brain doesn’t recall so much as reimagine, tainting the memory with a range of ingredients in the process: fragments of other occurrences, newly uncovered details, current thoughts, figments of the imagination. A memory is like a piece of forensic evidence, contaminated a little bit each time it is touched by human hands. Or a memory is like the jar of homemade raspberry jam that was canned by my mother in 1984, and is now arguably my most bizarre keepsake. Though it probably doesn’t taste good, the jam looks remarkably well-preserved, and as long as the airtight seal is intact I’m sure the berries (harvested in the garden of my childhood home) will stay edible for years to come. If I open the lid, if only for a spoonful, decomposition will speed up, the contents will transform until the jam is utterly unrecognizable.

The same frailty applies to the VHS cassette that came crashing into my life like an unexpected flashback. I’m not talking about the perils the video has endured: How it was left unharmed when burglars vandalized my family’s storage unit; how the DVD copies we made turned out to be blank; how the original cassette disappeared for a few stressful days and snapped inside my VCR after finally being located. No, I’m talking about the gradual, physical erosion that takes place every time the magnetic tape passes through the video player. While hardly discernible from one viewing to the next, the machine is nevertheless, slowly but surely, altering the recording of my mother.

4.

It is not surprising that the Internet eventually caught up with my mom. Googling her on a whim ten years ago, I was a little astonished to see her face pop up in a class photo taken with her pupils. I had a mixed reaction: The new digital world seemed like a sphere where she, who had passed away long before I got my first computer, didn’t belong. Such a response would be unheard of today. With countless archival records scanned and made publicly available by companies and institutions around the globe, having no online presence is something of an accomplishment, even for the long-since departed.

I’m conflicted about putting my mother out there. She is, after all, defenseless, and part of me feels, in an almost parental manner, the need to protect her. I know that publicizing her name will generate a new hit in the search engine, maybe the top entry, and that people looking for information about her in the future might encounter these scribblings by her son, who knew her only for six and a half childhood years. Recently, when I googled my mother, I got four hits, all from digitized back issues of Døves Tidsskrift, a periodical of the Norwegian deaf community. On page 12 in the issue dated February 6, 1987, there are two obituaries: One is by the principal at the school where she worked, the other by a close colleague and friend. Among a stack of old family documents that have been entrusted to me, I found no fewer than twenty-one xeroxed copies of the obituaries from Døves Tidsskrift. I’m clueless as to why so many were produced, and when Internet users from any corner of the planet can read the texts at the click of a button, the A4 duplicates come to seem redundant.

When I last visited my mother’s burial site, I noticed that a thin layer of moss growing on her grave has begun creeping into the carved inscription of her name. Soon enough the letters will be illegible and, in the end, for better or worse, the Internet will be my mom’s most permanent resting place. Perhaps this essay is my engraving on her digital monument. I like to think she’d be OK with that.

The nine-minute tape has also shape-shifted and dematerialized in the time since I digitized it, although it’s difficult to tell what percentage of the analog signals went missing in the conversion. It would seem natural to upload the AVI file as a supplement to this essay, but here my guardian instincts protest. I’m hesitant to release the only moving images of my mother into the wilderness of the public domain. But more than that, I’ve come to realize that something essential would be lost if the video were posted online. Most viewers would find nothing exceptional about the footage of my mom signing; on the contrary, I fear they’d be indifferent or flat-out bored.

The only part of the recording that comes remotely close to transmitting the halo that I see is that single, randomly shot image of her face. The smudged, oversaturated colors of the dilapidated VHS tape bring to mind pseudoscientific New Age “aura photography.” It’s a double exposure, so her semitransparent face floats over the curtain backdrop, almost like a ghost. It’s a little out of focus, causing her features to be blurred. Still, she does look beautiful.

Dedicated with love and gratitude to my father and my sister, for their strength and devotion.

Along with this essay, the video file has been acquired by New York University’s Fales Library & Special Collection, as part of Fales Library’s ongoing archiving of Triple Canopy.