We Go for the Union is an anonymous, undated nineteenth-century American painting. Titled, by curatorial fiat, after the political banner at its right, it depicts a group of men who are each, in varying ways, skilled in the manipulation of paint.

One man (of greatest height and most costly attire) holds a palette and narrow brush for applying precise touches. To this auteur’s right, a black man in stained overalls holds a bucket of paint at the ready. This paint has been applied across the background of a painting within the painting, a political sign featuring the likeness of George Washington. At far left, a strangely proportioned, muscular figure with pinched head and blurred features laboriously grinds blue pigment against a stone. An orange horizon emanates through the workshop windows, indicating, if not a clearly identifiable hour, then, perhaps, the sublime.

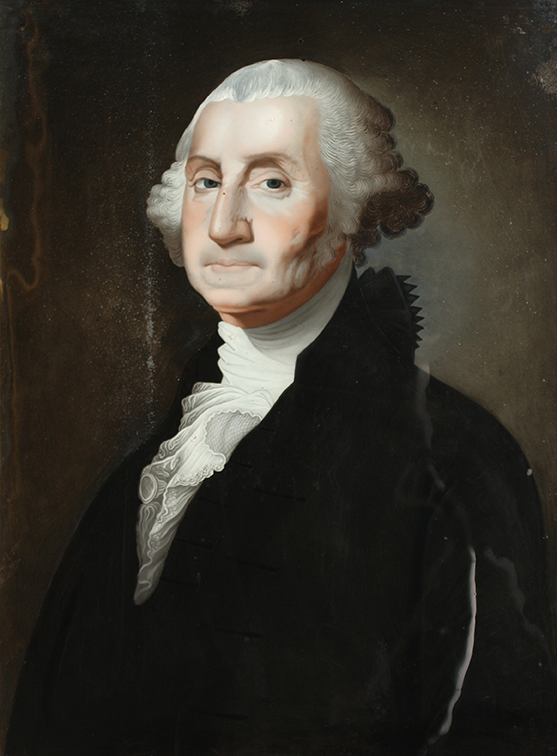

In this scene the labor of painting is divided into three, with only one worker accorded the status of artist: The giant, yellow-jacketed professional limns august features instantly recognizable as those of the union’s first president. The artist seems to work from memory, pausing in reserved admiration before the realistic image he apparently believes himself to have authored. Yet we know that this image is in fact a copy of Gilbert Stuart’s famous Athenaeum portrait, which Stuart himself never officially finished, instead copying it at least seventy-five times and selling each reproduction for $100. The Athenaeum is familiar to us through its appearance on numerous postage stamps as well as on the one-dollar bill for more than a century, but unattributed copies of it circulated long before its adoption as the face of US currency. (Stuart himself spent time in court suing unauthorized copyists and distributors, including one producer of copies on glass in Canton, China.) Even today, the familiarity of this jowly mien eerily echoes a comment by the critic John Neal, who wrote of Stuart’s Washington portraits, in 1823: ‘‘It matters not how a picture is painted, so that the copies are multiplied and received (if they resemble each other), as likenesses.… Thus we get accustomed to a certain image, no matter how it is created, by what illusion, or under what circumstances; and we adhere to it, like a lover to a mistress.’’

We Go for the Union displays, quite literally, the essential role of copying in early American painting. It points us in the direction of a history of American painting very different from the canonical zone inhabited by Stuart, a history not of schools but of likenesses, copies, a discourse of continually re-contextualized popular images that emphasizes neither originality nor singular authorship. This history resists academic study, not only because of a dearth of master artists and clear attribution, but because it is a history of regional itinerancy and diverse, sometimes eccentric technique. Characterized by a lack of institutional support or private patronage on a grand scale, as well as a paucity of written accounts, such art stands in part as the record of transactions between nonelites, what some might term an economy of “craft.” Such artworks additionally suggest that weak and collective forms of authorship were crucial to the development of singularly American visual styles and tastes.

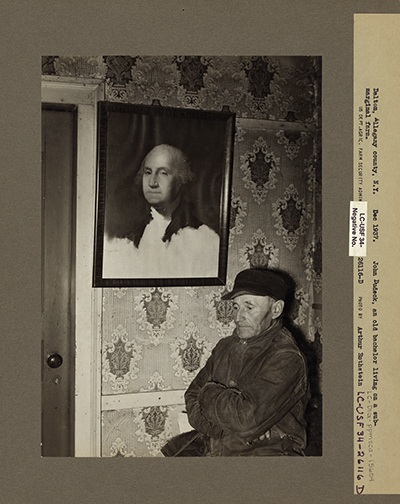

We Go for the Union entered public record in 1949, when it was purchased in Connecticut by two wealthy collectors, Colonel Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch. Bernice Chrysler was heir to the Chrysler fortune, and the pair had become interested in early American folk art while furnishing their Maryland hunting lodge, a sizable property named Pokety.

In the mid-1950s the painting was exhibited at the National Gallery in two shows of so-called American primitive paintings, as an exemplary item in a broad survey. In 1956 the Garbisches donated the painting to this museum, and it became part of the permanent collection there. The National Gallery soon lent it to two regional museums for additional surveys of American primitive paintings. In the 1970s the painting was loaned first to the White House; from there it traveled to the residences of US ambassadors in Lisbon, Portugal, and Bern, Switzerland, then to the offices of two Secretaries of Labor, then to the office of Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Andrew Cuomo. For the politicians who basked in the glow of its enigmatic sky, We Go for the Union was likely an example of genre painting, its particular history and style not paramount. From February to May of 2014, the painting was taken out of storage by the National Gallery for Pointing Machines, an installation created by this magazine, Triple Canopy, for the Whitney Biennial.

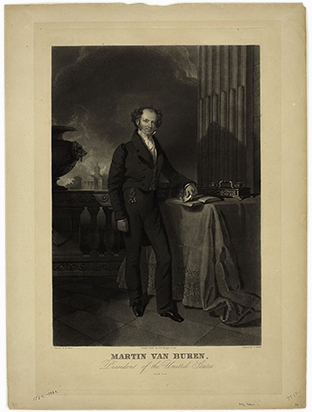

In each of the contexts named above, We Go for the Union has been valued, viewed, and instrumentalized in particular ways. When the painting was purchased by Colonel Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch, it became part of a broad collection encompassing works of thousands of anonymous artists who practiced in the American Northeast between the end of the eighteenth century and roughly 1840, when the daguerreotype first came into use. During this period, most Americans experienced and understood portraiture not by way of the finely worked academic canvases of John Singleton Copley or Gilbert Stuart, but rather via the production of itinerant portrait-makers known as limners,1 who advertised their services in local newspapers, renting temporary studios as they went from town to town. The limner was not always or exclusively a painter, but was also a profile artist, technician, and copyist. Throughout the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, printing techniques—wood engraving, mezzotinting, aquatinting, soft-ground etching, stipple-, crayon-, and pastel-manner engraving, and, after 1820, lithography—were, in America as in Europe, the primary and most efficient mode of creating images as multiples. Limners were seldom involved in the process of printing, but they did make use of preexisting images to represent living subjects quickly and in a convincing manner, deriving poses from English mezzotints, for example, or repeating popular motifs like Stuart’s Washington. One experiment in portraiture evidencing use of a preexisting image as a basis for a new likeness was undertaken by the engraver John Sartain, who in the early 1860s used a then twenty-five-year-old mezzotint plate of Martin Van Buren as the underlying structure for a portrait of Abraham Lincoln.

Limners sometimes worked with mechanical drawing and copying instruments as well as optical viewing devices, producing profiles, silhouettes, and painted portraits. The first advertisements offering such mechanically assisted—and therefore, some limners alleged, more “correct”—portraits appeared in American newspapers in the 1780s. The pantograph, a simple compass-like device, permitted point-to-point reproduction of images as well as scale changes, while the more involved physiognotrace produced profile likenesses by means of mechanical tracing. In 1796 the first notice promoting the physiognotrace was placed by the French artist J. J. Boudier, resident at 275 Front Street, Philadelphia, who offered likenesses from any vantage, to be completed “in a most striking manner, in a single sitting of about one hour.” Thus, the photograph was not the first form of mechanically produced image popular in the United States; at the end of the eighteenth century the physiognotrace and other drawing machines influenced the art of American portraiture as strongly as the daguerreotype would sixty years later.

The mechanical representational devices and optical instruments employed by limners were both touted and criticized. One observer wrote of the painter Charles Bird King, who as an itinerant artist in Maryland and Virigina from 1812 to 1819 invented his own mechanism for creating and reproducing proportionally accurate pictures: “He uses a slender rod of wire about a foot long, to ascertain the proportions of his picture, compared with the original.” King apparently used this device to create exactly proportionate images and reproductions. However, the same observer cautioned that “all mechanical aids are mischievous. The artist should depend alone on his eye.” Painters at this time were considered tradesmen, and many limners learned to paint through trade in sign and carriage decoration as well as apprenticeship to other painters. They traveled from state to state, their livelihoods often uncertain. The limner James Guild describes his “education” in the first decade of the nineteenth century as no small struggle. “Soon it began to rain and I in the wilderness accompanied by no friend, and all the consolation I had was in hoping for the better,” Guild writes in his diary. “O heaven what shall I do, was I born for misfortune? O, I am poorer than a beger, and I can never prosper.” Guild soon approaches an older painter who offers to instruct him “how to distinguish the coulers” for five dollars. “I consented to it and began to paint. He showed me one day and then I went to Bloomfield and took a picture of Mr goodwins painting for a sample on my way. I put up at a tavern and told a Young Lady if she would wash my shirt, I would draw her likeness.”

In newspaper advertisements, limners emphasized the cheapness and efficiency of their services, as well as their artistic versatility and concern for customer satisfaction. Some offered a full refund to the client not fully satisfied with the “likeness” produced. One detailed advertisement explains the numerous kinds of work on offer:

painting in the following Arts, viz Portait Painting in oil of all sizes, from busts to full figures; do. Painting with pastils [sic] or crayons, in a very cheap manner, which after glazing will appear almost equal to that of oil. Miniature painting, Hair-work, etc. Coach and Carriage painting done in the neatest and best manner, and embellished with gilding and drawing, after the most New-York fashions; Sign painting, lettering with gold leaf, and smalting, together with clock-face painting, etc. Copperplate engraving of almost every kind, together with Typographical on type-metal or wood.

Limners’ tendency to dip in and out of various technical discourses and professional roles suggests that their artistic labor was never fully distinguishable from other forms of work. Limners held a place in the American public sphere not unlike the local newspapers in which they advertised: Itinerant, they served a range of clients, causing images and information to circulate with them; variously skilled, they represented an image of the US citizen not beholden to the class and labor divisions of Old Europe. The 1804 appearance of a weekly column titled “The Limner” in a Hudson, New York, newspaper demonstrates the larger civil significance of the limner portrait as a record of social and economic negotiation and transaction, in which one American offered to represent another. The newspaper’s twenty-six-year-old editor, Harry Croswell, wrote the column pseudonymously, from the point of view of a fictional painter named Peter Pallet, who recorded his encounters with duplicitous citizens and politicians falsely claiming to “represent” their own characters or those of others. Pallet maintained that any true likeness must include the invisible content of character, the “furniture behind the face … particularly that generally called the brain,” as well as the heart, “with all its dark and light shades—all its rotten and defective specks, and even all its throbs and vibrations.”

As Croswell surely understood, print publication was instrumental to the creation of social bonds in the early republic. “The ‘we’ of the Constitution … is speaking to itself,” writes scholar Michael Warner in Letters of the Republic: Publication and the Public Sphere in Eighteenth-Century America (1999). “The evidently untraced origins and universal audience of the printed text allow the people always to be both authoring and reading, both giving and receiving its commands at once.” Readers of the Constitution, like readers of newspapers, discover themselves already engaged in sustained political discourse. They consent to be governed because the law described finds its basis in a real public, rather than in a transcendent, conceptual compact. An analogous argument about shared perception in the visual arts is taken up by Wendy Bellion in Citizen Spectator: Art, Illusion, and Visual Perception in Early National America (2011), an account of illusionism as a mechanism for the production of citizens. Bellion shows how trompe l’oeil unites viewers in a shared project of visual discernment: Its “instantaneous effect may be visual deceit, but its endgame is recognition.” Such interpretations of popular print and visual culture suggest that American “likeness,” as a discourse emphasizing the crucially participatory nature of printed and painted texts, represented a break with European legal and aesthetic codes, even as it co-opted, borrowed from, or built upon them. The limner was a key agent of such socially negotiated artworks.

By the 1830s, the American image market had become increasingly saturated. Mass-produced lithographs were purveyed by traveling peddlers to rural areas and were ubiquitous in cities. Currier and Ives2, the well-known printmaking firm, sold hand-colored black-and-white lithographic copies of maudlin genre and historical paintings by academically trained artists. Fine art’s entry into wide, high-quality circulation at an affordable price point—a Currier and Ives folio size cost fifteen cents—foretold the coming diminution of the market for limnings following the advent of photography, even as lithographs served as source material for limners. This rapprochement of academic and commercial art (or craft) was confirmed when in 1834 William Dunlap, founder of New York’s National Academy of Design, published A History of the Rise and Progress of the Arts of Design in the United States, which describes the work of academic painters as well as itinerant limners. Dunlap cites journal entries by artists and responses given to a survey that he had personally sent out to all the living American painters he felt noteworthy. The lifestyle, or business model—it is perhaps difficult to differentiate between the two—of the limner was increasingly recognized as a viable means of supporting the creation of art. A number of female artists joined the ranks of the heretofore mostly male profession, including Susanna Paine, whose journal of her travels in the 1830s and ’40s was published in 1854 as Roses and Thorns: Reflections of an Artist: A Tale of Truth, for the Grave and the Gay. Paine’s account depicts personal hardship in unflinching detail, proclaiming the hard-won nature of a limner’s painterly objectivity and also her own distance from settled middle-class life. The book’s subtitle shares in a widely held perception of the itinerant artist as an arbiter of a special kind of truth in lived experience.

When daguerreotyping began to be practiced in the US around 1840, many who had previously worked as limners set up studios offering the new photographic technique in addition to oil portraits and portraits painted from daguerreotypes. Continuing the custom of incorporating print images into paintings, former limners like Erastus Salisbury Field sometimes enlarged photographic images on canvas and painted over them. Many of Field’s paintings have been described as copied from photographs, but may in fact be painted-over photographic images; for instance, Betsey Dole Hubbard (circa 1860), nearly thirty inches in height, is an oil painting made over an enlarged photographic print on canvas. Some sitters requested that this process be reversed: They chose to be photographed with painted portraits commissioned at an earlier time, ensuring a double reproduction, of self and artwork, at a single cost.

Such practices show how value in vernacular American painting was less dependent on the concept of originality than on a kind of commercial circulation that privileged repetition of familiar images, motifs, tropes, and styles, as well as negotiation between sitter and artist. Often originating as copies, images produced by limners demonstrate the significance of weaker modes of authorship in the development of American visual culture. As popular literature on limners indicates, people found the perception of limners meaningful, even if—and sometimes because—the images they produced were unoriginal. Limner paintings also describe an unorthodox interaction of painting and technology previous to “the trajectory from photograph to painting,” which, according to Michel Foucault, characterizes all painting after 1839. These unoriginal, sometimes technical images contradict the advice of hyperrealist portraitist Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingrès, who in 1862 slyly admonished the modern painter, “C’est très beau, la photographie, mais il ne faut pas le dire.”3

The Garbisches, who lifted We Go for the Union out of rural obscurity and into institutional care in the late 1940s, typified a certain kind of collector of American folk art. Bernice Chrysler Garbisch, with her Chrysler legacy, had a sense of responsibility to the nation; she and her husband believed in a postwar American ascendency and wanted to assemble an array of images and objects that described a concertedly American taste.

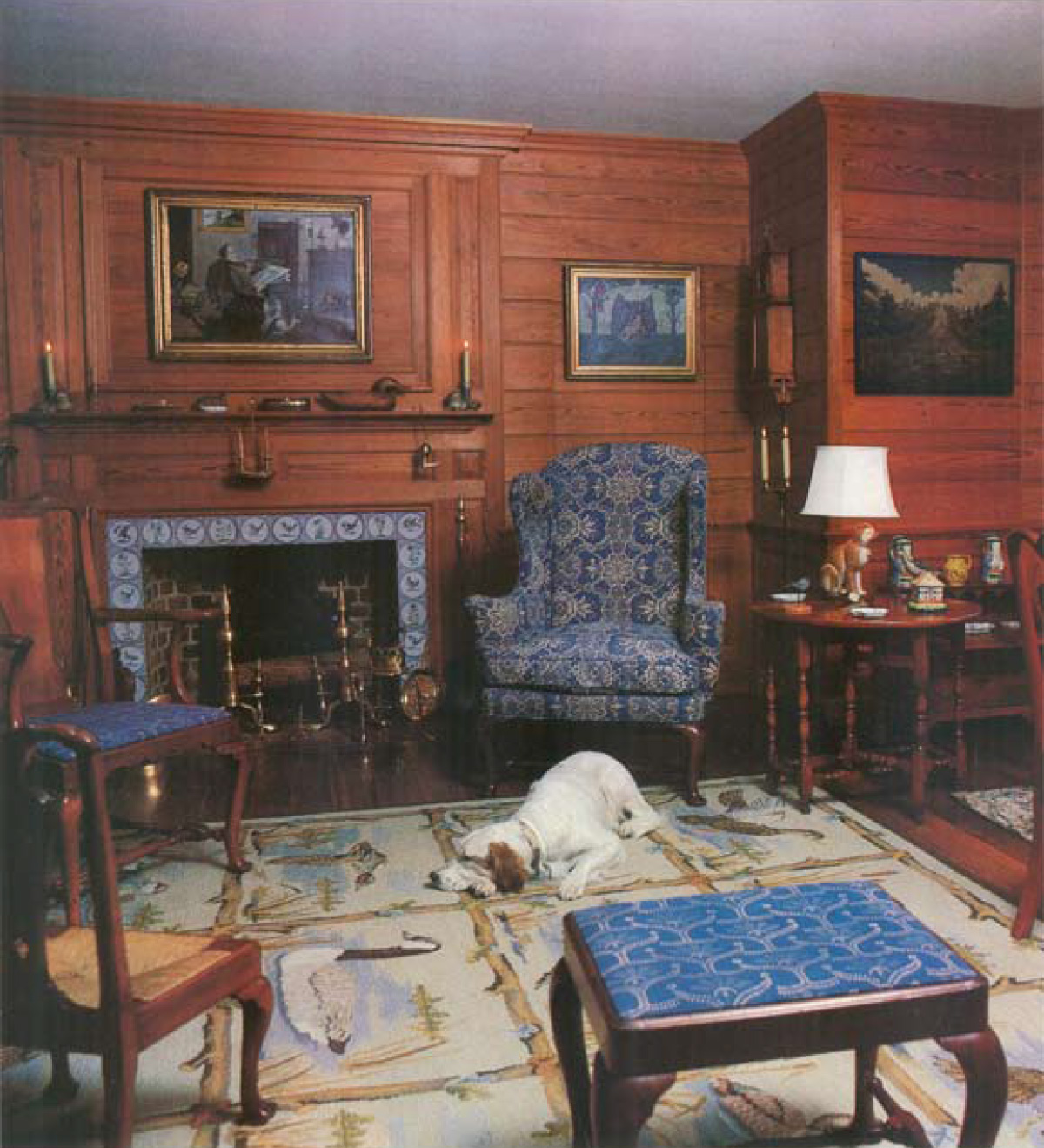

The Garbisches also liked a bargain, and folk art was inexpensive. Their collection, purchased between 1946 and 1979, was not an exhaustive or academic review of a historical timespan or series of stylistic trends but was rather designed and destined simply to fill a house. This house, the imposing Pokety Farms, the Garbisches’ Maryland residence complete with private bowling alley and elaborate boxwood gardens, was both the impetus and frame for the couple’s assembly of “museum-like Americana in unmuseum-like comfort,” as a 1959 Vogue article documents.

Pokety’s five-hundred-and-forty acres, part of the land granted by Lord Baltimore to Anthony Le Compte, were bought by Walter P. Chrysler in 1929 for a shooting place. After Mrs. Garbisch, the former Bernice Chrysler, acquired it in 1945, she and Colonel Garbisch spent three and a half years remodeling and expanding it, much of the time searching the countryside for abandoned and unrestorable eighteenth-century houses. From these: choice heart pine floor and wall boards for Pokety woodwork, beautiful hand-blown glass for Pokety windows, handmade bricks for Pokety fireplaces, mellowed hardware for Pokety doors. Meanwhile, their outstanding collection of primitives was growing as they tracked down, in their Americana detective work, many prizes of untutored imagination in private houses and byway antique shops.

Precise and focused as they were in this thematic restoration or “Americana detective work,” so the Garbisches seemed in many things. Bernice and the Colonel, as he preferred to be called, wed in 1930. He was a football star at West Point, served in the Corps of Engineers in the Second World War, and came home to act as chairman of the Grocery Store Products Company. She was a mother and wife and educated, knowledgeable about art and decoration; prewar continental stints had afforded the opportunity to purchase Picassos and Manets. At home, Bernice was shrewd and punctual. “Everyday at 5 o’clock she made martinis, and she could mix great ones, filling them to the top without ever spilling a drop,” writes Vincent Curcio, quoting a relative, in Chrysler: The Life and Times of an Automotive Genius (2001). “She always drank Heublein’s Wilshire gin, which was their economy label, saying it was as good as anything made, and why pay premium prices? I remember her sitting and playing solitaire by the hour, too, waiting for the Colonel, who never seemed to come home on time, to her great annoyance.”

The Garbisches had originally planned to decorate Pokety in the English style, but in the aftermath of World War II the American elite, having ostensibly saved Great Britain from an execrable fate, wished to reflect the nation’s new international status in a carefully defined lifestyle at home. The establishment, around the same time, of Colonial Williamsburg, the Fenimore Art Museum, and the Shelburne Museum suggested a broader turn toward colonial arts and crafts. Similarly, the work of collectors of folk music like Alan Lomax and Harry Smith documented the emergence of authentic American song from British and European traditions, and stoked the revival of Delta blues and Appalachian ballads. The Garbisches decided to fill Pokety with examples of eighteenth-century American furniture and roughly contemporary artworks. The paintings they began purchasing to fill this role (and their walls) were nonacademic, “primitive” paintings. In spite of the fine Picassos hanging in the Carlyle apartment, the Garbisches, by their own efforts and ambition, became best known for this collection, which grew to encompass more than 2,500 works, mostly dated between 1785 and 1840.

The Garbisches claimed not to subscribe to any particular ideology in their purchasing—which is to say they knew what they liked and bought a lot of it, with or without the advice of experts. As the Colonel once told Nancy Druckman, director of the folk art department at Sotheby’s, “My dear, I buy it by the bushel-basket full.” The Garbisches were, additionally, regionalists, focusing on the Northeast. In the Garbisches’ first year of collecting, 1946, they purchased paintings by prolific Maine limner William Matthew Prior and coach painter, Quaker minister, and folk artist Edward Hicks, of Pennsylvania. In 1949 alone, the Garbisches purchased 480 pictures. She preferred needlework and portraits; he liked scenes of daily life and illustrations of games and sports. The Garbisches cared little for the grand canvases of a Romantic painter such as Thomas Cole, preferring works with a decided flatness and lack of modeling, qualities that characterize the painting of commercial limners whose pictures circulated via popular channels. As the renown of the Garbisches’ collection grew, their paintings were included in exhibitions and became subjects of scholarship. But, fittingly enough, it was the commercial print journal that did the most to reproduce and disseminate the Garbisches’ paintings during their lifetimes. Publications like Home Decorating, LIFE, and the New York Times Magazine printed photographs of Pokety’s ornate interiors in glossy color, construing the paintings as emblems of style as well as representational works. (This was in no way unusual: Articles in the 1910s and ’20s in magazines such as House and Garden, Country Life, and House Beautiful, which aimed to educate homemakers about decorating in a distinctly national style, contained many of the first widely reproduced images of American folk art.)

Beginning in the 1950s, the Garbisches became aware of the broader cultural implications of their collecting and generously donated to more than twenty American museums, with the National Gallery receiving three hundred paintings and one hundred works on paper. Writing in Art in America in 1954, in a jointly authored article, the Colonel and Bernice describe the “most exciting venture” they had undertaken. “It has stimulated us to a great deal of study about our country’s early days and ways, and has awakened us to a fuller understanding and deeper appreciation of our national heritage,” they wrote.

By the time we had gathered a representative group of these pictures, we had arrived at the very definite conclusion that good American primitive paintings reflect extraordinary creative imagination and possess unusual artistic values. Therefore, we felt, they merit an important place not only in the history of American art but in the history of world art as well. Such an exalted appraisal, we realized, was not generally acknowledged, and we did not think it could be until a comprehensive collection of these paintings was made available for the general public to see and for art historians, students, and critics to evaluate. It was then that we decided to assemble such a collection and give it to the nation. From that time on we were not just collecting for our Maryland home but with an art museum in mind.

At this time, the Garbisches still termed the paintings on which they focused “primitive”; however, after lending works to a 1968 touring show in France and Belgium that advertised “Peintures Naïves,” the Garbisches adjusted their terminology. At the behest of French novelist and art historian André Malraux, they discarded “primitive” in favor of the apparently happier “naive.” This switch in nomenclature dispensed with the notion, however implicit, that the limner was, by definition, uncultured. A naive painter, so called, might be ignorant, but he was not absolutely opposed to (or, for that matter, previous to) American culture.

A couple to the last, the Garbisches died within hours of each other in December 1979. In previous years, the pair had decided that, upon their deaths, their entire collection—every embroidery and serving spoon and basin stand at Pokety Farms—would be liquidated in a historic sale that would enhance their notoriety and earn substantial sums. The Garbisches did not shy away from celebrity and had often been dissatisfied with museums’ display (or warehousing) of the works they donated. They must have known that the auction would be a moment of unprecedented access and fame for the collection, and that it would be glamorous as only something final and, in a certain sense, destructive can be. The power of their personalities and the environment of their home, which brought together the priceless and the minor, the exceptional and the merely charming, made all the works more valuable. This value was further amplified in the production of the spectacle by Sotheby’s, which publicized and even literally published the Garbisches’ collection—in its own auction catalogues and in articles about the sale that appeared in numerous local and national magazines and newspapers. Works created by limners—already exemplary of the incessant reproduction of images and texts—circulated adjacent to the society pages, housekeeping tips, and news of the Iran hostage crisis.

Sotheby’s held the auction during Memorial Day weekend in 1980. Nancy Druckman, who was present at the house for the sale, recalled the pomp with which Pokety staff served the Sotheby’s team, providing sherry aperitifs with lunch. Before the auction took place, the National Gallery wished to remove many of the most significant, large-scale paintings, which had been willed to the museum by the Garbisches. Sotheby’s, sensing that denuding the rooms of Pokety Farms would be bad for business, had the paintings photographed before their departure. Sotheby’s made Ectachrome prints, which depicted the paintings as well as their original frames, to scale and hung them in place of the absented canvases. These reproductions served to recreate the domestic scenes celebrated in lifestyle magazines.

The auction itself was another great display, making use of Pokety’s lavish interiors and the expansive lawn with views of LeCompte Bay. Some 20,000 visitors passed through the house during the course of that Memorial Day weekend, with 1,000 bidders in each of four sessions of sale and total earnings of $3,903,503, more than any previous American house sale or collection of Americana. On Saturday, three yachts dropped anchor in the Chesapeake Bay beyond the Garbisches’ back lawn, with passengers cheering when record prices were registered. Bids also came in by telephone from nine other countries, including South Africa and Japan. Bill Cosby spent $250,000 on a blockfront kneehole bureau.

In light of the rousing success of the sale of the Garbisches’ collection, the continued marginalization of the figure of the limner is an odd loss. To the Garbisches, the limner was a metonym for an abstraction known as “the American people.”

The limner’s style was plain, forthright, and delightfully vital; uncorrupted by an education in the history of art, the limner was a painter of untutored honesty. To understand the limner’s work one had only to enjoy it.

The lack of critical discourse surrounding the limner’s work neither began nor ended with the Garbisches’ collecting. The limner was overshadowed by the celebrity and eccentricity of the Garbisches’ activities—which were seen as unusual enough to warrant a three-day symposium organized by New York’s Museum of American Folk Art, in November 1985. Here museum directors as well as auction house personnel shared information about how the Garbisches’ purchasing had affected the greater field (and enjoyed a viewing of works from the Garbisch collection at the Sky Club in the Pan Am building’s penthouse). Writing to announce the impending confab, Robert Bishop, director of the Museum of American Folk Art, proclaimed the Garbisches “colorful,” if not particularly shrewd, collectors.

I first met Colonel Garbisch nearly twenty years ago when, as a young man, I earned my living as a folk art dealer. As a visitor, one year, to the annual Winter Antiques Show at the Park Avenue Armory in New York, I stood by and watched him acquire two paintings by the remarkable New Hampshire artist, Dana Smith, for $14,000—paintings that I had originally sold to another dealer weeks earlier for $285 each.

And, more damningly,

I remember one time in particular, after having met the Garbisches, when I was visiting a small auction house in Greenwich Village to preview a collection of art from a forthcoming sale. I was astonished to discover an extraordinary lifesize portrait, Mrs. Ostrander and her Son, Titus by Ammi Phillips. I promptly called the Garbisches, who were on vacation in Florida, told them about the painting and suggested that they authorize me to acquire it for their collection. The Colonel asked me what I thought the hammer price might be. I indicated that somewhere between $800 and $1000 would bring the picture home. The Colonel barked in reply, “Phillips is not really that interesting as a painter. We have several examples in our collection, and I would never consider paying that kind of money for a picture by that artist.” The painting was acquired by Alice Kaplan, a trustee of the Museum of American Folk Art, and remains today one of the unchallenged masterpieces of American naïve art.

As this mildly acrimonious account suggests, the Garbisches’ thinking did not always align with expert opinion, nor did their collection always contribute to the creation of strong historical narratives. Their cataloging system was simple to the point of obfuscation: Each item was numbered in the order in which it had been acquired, and there was often little information beyond the date and location in which it had been purchased. Deborah Chotner, the National Gallery curator in charge of paintings donated by the Garbisches, found the documentation she received extremely slim: “I expected a moving van full of documents to drive up to the back of the gallery and there was only this manila envelope with a sheet on each object.”

A partnership, if one may call it that, undertaken by the Garbisches with the Whitney Museum—beginning in 1968, when the Garbisches donated twenty-four paintings—was significantly less felicitous than the National Gallery bequest. In 1999, following a concerted program to update the museum begun in the 1980s and including ambitious but failed plans to expand the Breuer building, the Whitney decided it required additional funds to purchase the work of better-known twentieth-century artists and so deaccessioned twenty-three of the twenty-four Garbisch paintings. The museum selected these canvases and watercolors “based on recommendations from outside scholars hired to evaluate the collection,” the New York Times reported. The paintings, detailed in a Sotheby’s press release and priced at around $25,000 each, ranged from portraits (the likeness of “a refined woman wearing a black dress with cream trim and a locket necklace who is reading a passage from a book entitled True Friendship”) to religious imagery to local color (“a charming watercolor picturing two girls and a boy picking apples amidst a lush countryside”).

The Whitney kept one painting from the Garbisches’ collection, A. Logan’s Circus, of 1874, because it was seen as a visual rhyme with Alexander Calder’s Circus mobile, owned by the museum. A second painting, an anonymous work from circa 1840, titled Indian Encampment, failed to sell at auction and so was “bought in” by the Whitney, meaning that it is now housed in the Whitney’s off-site storage facility in Chelsea but is no longer part of the permanent collection. Indeed, the Whitney’s online collection includes no entries for artworks created prior to 1900, suggesting that the museum currently possesses no such works.

The Whitney’s deaccessioning of works donated by the Garbisches and its related disinterest in the practices of the limner become more telling when viewed in the broader context of the Whitney’s history, as in its earliest days the museum was closely associated with folk art. The first American show of folk art in an urban setting occurred in 1924 at an early incarnation of the Whitney, the Whitney Studio Club, an experimental exhibition space overseen by Juliana Force, who was then personal assistant to Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, the club’s patron. The 1924 Studio Club show was the result of a visit by painters Charles Sheeler, Robert Laurent, and Yasuo Kuniyoshi to an Ogunquit, Maine, art colony, where guest cottages were decorated with paintings and other works by nonacademic artists and craftsmen. The three modernists “were astonished to discover that this unfamiliar art embodied aesthetic principles that they had previously understood as purely modern.” Their collectively organized Studio Club show included “naive engravings, paintings on velvet, portraits by untutored artists, a cigar-store Indian, a ship’s figurehead, a brass bootjack, and pewter serving bowls” and was reviewed by the New York Times as the “odds and ends of not very early decorative art.” The Brooklyn Eagle focused on the show’s revision of the history of the country’s art:

The Cigar Store Indian has found a home. Crowded away from his natural habitat by the United Cigar Stores, he was a man without a country. … Some of the other examples of American primitives on view … (especially the paintings) serve as the much needed first link in the chain of American art. In so being, they explain the last link, which is in a way a conscious imitation of the unconscious flowering of our ancestors’ art spirit.

A second Studio Club show followed in 1927. “An Exhibition of Early American Paintings” drew on the collection of Isabel Carleton Wilde, who like Juliana Force, was a noted collector of folk art. And it was not just modernist painters whose work came to seem “a conscious imitation of the unconscious flowering of our ancestors’ art spirit.” Holger Cahill, curator of two significant 1931 exhibitions at the Newark Museum, “American Primitives: An Exhibit of Paintings of Nineteenth Century Folk Artists” and “American Folk Sculpture: The Work of Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century Craftsmen,” as well as 1932’s major “American Folk Art” survey at MoMA, attested to a more general “kinship” between folk art and modernism. Folk art aided in a modernist “revolt against the naturalistic and impressionistic tendencies of the nineteenth century,” promoting a counterintuitive return, on modernism’s part, to “sources of tradition.”

When the Whitney became a full-fledged museum in 1931, Force, now the director, lived above its West Eighth Street entrance in an apartment riotously decorated with examples of folk art, Victoriana, and contemporary American paintings. The Whitney, already unusual for its origin as an informal artists’ club run by two women, represented a break with standard institutional practices in other ways as well. The founding was the direct result of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s rejection of a donation of modern American paintings amassed by Vanderbilt Whitney over her years as doyenne of the Whitney Studio. And there was Force’s influence on the look and feel of the museum’s space—“feminized” galleries of wall-to-wall carpeting and tufted benches, “like a magnificent home,” as one visitor gushed in Vogue. The New York Times lingered over the remarkable use of bright color throughout the galleries:

The walls of the sculpture gallery are painted powder blue, against which marble and bronze are defined sharply. Two of the picture galleries have white walls and white velvet curtains and two others have canary yellow walls with blue carpets and hangings. Another gallery is rose colored … [while] two others have been finished in grey and two have cork walls. … The coloring of the walls … has necessitated careful hanging of the pictures to obtain the most harmonious effects.”

This report further proclaimed, “This is a museum founded, maintained and managed by artists, since Mrs. Whitney, the curator and his assistants are sculptors and painters.” The Whitney Museum, carrying on the spirit of the Studio Club on a larger scale with this piquant decor, refused to draw a sharp distinction between decoration and artwork, between artist and curator. Additionally, a main tenet of the Whitney’s Biennials and other group exhibitions was that prizes should not be awarded to the few but that funds must rather be used to purchase a variety of artists’ works for the collection. This stylish museum was an attempt to prove that American art could encompass a broader field than had been imagined elsewhere, while still impressing and educating audiences. The Whitney’s lack of concern for canons and celebrity artists is also reflected in Florine Stettheimer’s 1942 painting The Cathedrals of Art, in which Juliana Force, soignée in a dress and matching hat of seafoam blue, looks on at the antics of the New York art world. Force stands before the dim specter of an orientalist sculpture made by Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney (who in her lifetime authored numerous mediocre plastic works), a distinct agent in spite of the questionable taste of her benefactress. Elsewhere, male museum directors gambol with prizewinning children or relax in the reassuring company of massive works by Picasso and Matisse. Here the Whitney Museum seems hospitable to limners, both past and present.

However, one year after Juliana Force’s 1948 death, the Whitney family, ignoring advice to the contrary by museum staff, sold all of the museum’s eighteenth-century and nineteenth-century holdings. (Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney had passed away in 1942.) This sale, including works by Winslow Homer, John La Farge, and James Audubon, was not particularly lucrative, first because the Whitney family had cherry-picked the most valuable items for their own collections, second because such artwork was then out of style and did not fetch high prices at auction. Though the Whitney would continue to exhibit and, starting in 1964, accept donations of nineteenth-century works, incoming capital was now earmarked for twentieth-century acquisitions. One wonders if the Garbisches understood the implications of this one-way street when they made their donation. A museum built on principles of collectivity and unorthodox, if not antinomian, conceptions of what might make a given work of art important—a museum privileging style and social life over single authors—became a site to which the American public was invited to view the interminable death of canonical modernism, via Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art, et al., and lately, in a burst of presabbatical glory, the monumental commodities of Jeff Koons.

The Whitney’s 1999 deaccessioning of works from the Garbisch collection was a matter of course. The artworks might as well have been a collection of copies; they emerge from networks of frequently reproduced popular images and motifs and show the influence of the working method of the limner, who reproduced as much as, and even if, he or she authored; who sold his or her products to a wide array of individuals at affordable cost. The Garbisches, motivated by a decorative impulse that subsequently became the impulse to take a kind of democratic, if misguided, survey of the arts of the nineteenth-century American Northeast, may as well have owned a collection of copies—or, in any case, it mattered less that the artworks they collected were originals than that they were examples of a particular period and style. The Garbisches exhibited, displayed, and otherwise presented and published the works they purchased in contexts that emphasized the cumulative nature of this work. They made their aesthetic points in bulk. Such paratactic tendencies did not sit well with a museum continually struggling to find its identity, even nearly seventy years after the death of its first, visionary director. Limners’ work was, apparently, not the stuff of which a canon might be made.

The presence of We Go for the Union in the 2014 Whitney Biennial thus serves as a reminder of the powerful way in which the meaning of an image alters in circulation. When an image moves, when an image is copied and recontextualized, its authorship, value, putative interpretation and origin also change.

Framed throughout this essay as an art object primarily significant for its circulation history, We Go for the Union provokes questions about how American art markets as well as institutional collections and broader art historical narratives might alter if canonizing impulses (not to mention the competing technology of photography) had not been strong enough to displace the limner from a central place within such markets, collections, and narratives. Locating the limner—with this figure’s attendant methodological and professional heterogeneity, with his or her technical images and entrepreneurial tendencies—at the center of a story of American art causes us to consider the possibility that American culture, in which the space between myth and its commercialization has always been paper thin, has also always been a matter of proprietary roles rather than ex nihilo inspiration and invention. As we consider the painters depicted in We Go for the Union we are not sure if we behold artists, or tradesmen, or both. We are not sure if the painters themselves “go” for the Union, or if they are merely providing a service for others who do. The author we discover here, the limner-author, more closely resembles a proprietor than a genius or hero. He or she manipulates commonplace images for a fee, locating the likeness of the client within a preexisting pictorial supply, reflecting the client’s concerns and desires within this preexisting visual context.

The power of the proprietary gesture to shape not just the single work of art but also longer histories is reflected in a piece of nonsensical handwritten text, discovered on the back of a 1954 black-and-white photographic reproduction of We Go for the Union, purchased on eBay from a third party selling ephemera from the archives of the Baltimore Sun, yet another print vehicle by means of which the Garbisches’ collection circulated. The anonymous script, likely penciled in by some member of the Sun’s staff at the request of the Garbisches, titles the painting Nullification and provides an erroneous date along with what is therefore likely an erroneous interpretation, asserting, “Ptd by unknown artist in heat of argument c 1830 over Sovereignty of States.” The script additionally proclaims, as if ventriloquizing the ridiculous artist figure reproduced on the photograph’s front, “Please do not use term ‘Garbisch Collection.’ The Garbisches request, instead, ‘Collection of Colonel and Mrs. Edgar W. Garbisch,’ or ‘Colonel + Mrs. Garbisch’s Collection.’” Here, in a demonstration of the (perhaps fleeting) tyranny of weak authorship, the Garbisches make, of a reproduction of a limner painting, a hastily sketched likeness of themselves.

Title-page images

Section One. “We Go For the Union,” ca. 1840–50, oil on canvas.

Section Two. Charles Bird King, The Itinerant Artist, ca. 1830, oil on canvas.

Section Three. Edward Hicks, Penn's Treaty with the Indians (ca. 1840/44), ca. 1979, 25 × 30". Collection of Frank B. Rhodes. Provided to the estate of Colonel Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch by Sotheby Parke-Bernet.

Section Four. A. Logan, The Circus, 1874, oil on canvas, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; gift of Edgar. William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch.

Section Five. Installation view: Triple Canopy, Pointing Machines, 2014, Whitney Biennial 2014, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

Bibliography

Barratt, Carrie Rebora. “Faces of a New Nation: American Portraits of the 18th and Early 19th Centuries.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 61, no. 1 (Summer 2003): 3–56.

——, and Ellen Gross Miles. Gilbert Stuart. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2004.

Bellion, Wendy. Citizen Spectator: Art, Illusion, and Visual Perception in Early National America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011.

Benes, Peter, and Jane Montague Benes. Painting and Portrait Making in the American Northeast. Boston: Boston UP, 1995.

Benjamin, Walter. “Unpacking My Library: A Talk About Book Collecting.” In Illuminations, edited by Hannah Arendt and translated by Harry Zohn, 59–67. New York: Schocken Books, 1969.

Biddle, Flora Miller. The Whitney Women and the Museum They Made: A Family Memoir. New York: Arcade, 1999.

Bishop, Robert. “Letter from the Director.” Clarion 52 (Fall 1985): 17.

Brown, Richard D. Knowledge Is Power: The Diffusion of Information in Early America, 1700–1865. New York: Oxford UP, 1989.

Burroughs, Alan. Limners and Likenesses: Three Centuries of American Painting. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1936.

Cahill, Holger. American Folk Art: The Art of the Common Man in America, 1750–1900. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1932.

Chotner, Deborah. American Naive Paintings. Washington, DC and Cambridge, UK: National Gallery of Art and Cambridge UP, 1992.

Clayton, Virginia Tuttle, Elizabeth Stillinger, and Erika Lee Doss. Drawing on America’s Past: Folk Art, Modernism, and the Index of American Design. Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2002.

Cobb, Josephine. “Prints, The Camera, and Historical Accuracy.” In American Printmaking Before 1876: Fact, Fiction, and Fantasy: Papers Presented at a Symposium Held at the Library of Congress, June 12 and 13, 1972, 1–10. Washington, DC: Library of Congress, 1975.

Crimp, Douglas, and Louise Lawler. On the Museum’s Ruins. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1993.

Curcio, Vincent. Chrysler: The Life and Times of an Automotive Genius. Oxford, UK: Oxford UP, 2001.

Druckman, Nancy. “American Folk Art from the Garbisch Collection.” In Art at Auction: The Year at Sotheby Parke-Bernet, 1974–75, 322–31. New York: Viking Press, 1975.

Dunlap, William. History of the Rise and Progress of the Arts of Design in the United States. New York: George P. Scott and Co., 1834.

“Fashions in Living: Collected American Elegance: Pokety, the House of Colonel and Mrs. Edgar Garbisch.” Vogue (February 1959): 176.

Forbes, Esther. Rainbow on the Road. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1954.

Forsberg, Diane. A Useful Trade: Nineteenth-Century Itinerant Portrait Artists. Brattleboro, VT: Brattleboro Museum and Art Center, 1984

Foucault, Michel. “Photogenic Painting.” In Photogenic Painting: Gérard Fromanger, edited by Sarah Wilson and translated by Dafydd Roberts, 81–104. London: Black Dog Publishing, 1999.

Friedman, B. H. Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney: A Biography. Garden City: Doubleday, 1978.

Garbisch, Edgar William, and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch. “Foreword … American Primitive Painting.” Art in America (May 1954): 95.

Goldman, Judith. “People are Talking about: Collecting: Auction Boom….” Vogue (September 1980): 523.

Goode, Stephen. “Naive Paintings of America’s Past.” Insight on the News (September 24, 2001): 38.

Grafly, Dorothy. “The Whitney Museum of Art.” The American Magazine of Art 24, no. 2 (February 1932): 92–102.

Greenhalgh, Adam. “‘Not a Man but a God’: The Apotheosis of Gilbert Stuart’s Athenaeum Portrait of George Washington.” Winterthur Portfolio 41, no. 4 (Winter 2007): 269–304.

Griffin, Tim. “Compression.” October 135 (Winter 2011): 3–20.

Guild, James. “The Education of James Guild.” In Quest for America 1810–1824, edited by Charles L. Sanford, 50. Garden City: Anchor Books, 1964.

Haberly, Lloyd. “The American Museum from Baker to Barnum.” New York Historical Society Quarterly 42 (April 1958): 142–169.

Harris, Neil. The Artist in American Society; The Formative Years, 1790–1860. New York: G. Braziller, 1966.

Healy, Daty. “A History of the Whitney Museum of American Art, 1930–1954.” PhD diss., New York University, 1960.

Heslip, Colleen C. Between the Rivers: Itinerant Painters from the Connecticut to the Hudson. Williamstown, MA: Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, 1990.

Hill, Joyce. “New England Itinerant Portraitists.” In Itinerancy in New England and New York: 1984 Annual Proceedings of the Dublin Seminar for New England Folklife, edited by Peter Benes and Jane Montague Benes, 150–71. Boston: Boston UP, 1986.

Hills, Patricia. The Painters’ America: Rural and Urban Life, 1810–1910. New York: Praeger, 1974.

Jaffee, David. A New Nation of Goods: The Material Culture of Early America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010.

Joselit, David. After Art. Princeton: Princeton UP, 2013.

——. “What to Do with Pictures.” October 138 (Fall 2011): 81–94.

Krauss, Rosalind. “Photography’s Discursive Spaces: Landscape/View.” Art Journal 42, no. 4 (Winter, 1982): 311–319.

Lasser, Ethan W. “Selling Silver: The Business of Copley’s Paul Revere.” American Art 26, no. 3 (2012): 26–43.

Levin, Gail. “Between Two Worlds: Folk Culture, Identity, and the American Art of Yasuo Kuniyoshi.” Archives of American Art Journal 43, no. 3/4 (2003): 2–17.

Levine, Lawrence W. Highbrow/Lowbrow: The Emergence of Cultural Hierarchy in America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1988.

Lipman, Jean, and Alice Winchester. The Flowering of American Folk Art, 1776–1876. New York: Viking Press, in cooperation with the Whitney Museum of American Art, 1974.

——. Primitive Painters in America, 1750–1950. An Anthology. New York: Dodd, Mead, 1950.

Little, Nina Fletcher. Itinerant Painting in America, 1750–1850. Cooperstown: Farmers’ Museum, 1949.

Lorente, Jesús Pedro. The Museums of Contemporary Art: Notion and Development. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing, 2011.

Lyons, Maura. William Dunlap and the Construction of an American Art History. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2005.

Neal, John. Observations on American Art: Selections from the Writings of John Neal (1793–1876). Edited by Harold Edward Dickson. State College: Pennsylvania State College, 1943.

North American Print Conference, and Wendy Wick Reaves. American Portrait Prints: Proceedings of the Tenth Annual American Print Conference. Charlottesville: Published for the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, by the University Press of Virginia, 1984.

Paine, Susanna. Roses and Thorns. Or, Recollections of an Artist: A Tale of Truth for the Grave and the Gay. Providence: B. T. Albro, Printer, 1854.

Pennington, Estill Curtis. Lessons in Likeness: Portrait Painters in Kentucky and the Ohio River Valley, 1802– 1920: Featuring Works from the Filson Historical Society. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2011.

Rather, Susan. “‘The Limner’: Harry Croswell, Newspaper Politics, and the Portraitist as a Public Figure in the Early Republic.” In Shaping the Body Politic: Art and Political Formation in Early America, edited by Maurie Dee McInnis and Louis P. Nelson, 231–267. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2011.

Reif, Rita. “Great Expectations for a ‘House Sale.’” New York Times, May 23, 1980, A18.

——. “$20.3 Million Art Sale Sets Record.” New York Times, May 25, 1980, 1.

Rigal, Laura. The American Manufactory: Art, Labor, and the World of Things in the Early Republic. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1998.

Roberts, Jennifer L. Transporting Visions: The Movement of Images in Early America. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014.

Schapiro, Meyer. “Courbet and Popular Imagery: An Essay on Realism and Naïveté.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes IV (1941): 161–91.

Schimmelman, Janice Gayle. American Imprints on Art Through 1865: Books and Pamphlets on Drawing, Painting, Sculpture, Aesthetics, Art Criticism, and Instruction: an Annotated Bibliography. Boston: G. K. Hall, 1990.

Schwarz, Heinrich, and William E. Parker. Art and Photography: Forerunners and Influences. Selected Essays. Layton, UT: Peregrine Smith Books, 1985.

Solis-Cohen, Lita. “Record House Sale: Garbisch Sale at Pokety.” The Maine Antiques Chronicle (June 1980): 60–69.

Sollors, Werner. Ethnic Modernism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 2008.

Sotheby Parke Bernet. The Garbisch Collection: Exhibition ... May 8 ... May 12, 1980 : Auction ... May 12, 1980. New York: Sotheby Parke Bernet Inc., 1980.

Sotheby’s. Important Americana: Furniture and Folk Art: Auction, [January 16 and 17, 1999]. New York: Sotheby’s, 1999.

Talmey, Allene. “Features: The Whitney Museum of American Art.” Vogue (February 1940): 94–95, 131–33.

Troyen, Carol. “Maxim Karolik and Folk Art.” The Magazine Antiques 159 (April 2001): 588–599.

Vogel, Carol. “INSIDE ART: Casting Folk Art to the Winds.” New York Times, January 8, 1999, E38.

Wallach, Alan. Exhibiting Contradiction: Essays on the Art Museum in the United States. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1998.

Warner, Michael. The Letters of the Republic: Publication and the Public Sphere in Eighteenth-Century America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1992.

Whitney Museum of American Art. Catalogue of the Collection. New York: Published by William Edwin Rudge for the Whitney Museum of American Art, 1931.

——. First Biennial Exhibition of Contemporary American Sculpture, Watercolors and Prints: December 5th, 1933 to January 11th, 1934. New York: The Whitney Museum of American Art, 1933.

——. Juliana Force and American Art: A Memorial Exhibition, September 24–October 30, 1949. New York: The Whitney Museum of American Art, 1949.

——. The Whitney Studio Club and American Art, 1900-1932: May 23-September 3, 1975. New York: The Whitney Museum of American Art, 1975.

Winchester, Alice. “Paintings for the People.” Art in America 46 (1954): 96.

A Note on “I Would Draw Her Likeness”

This essay was researched and written on the occasion of Triple Canopy’s participation in the 2014 Whitney Biennial and reflects certain aspects of the magazine’s installation, Pointing Machines. The essay may be read as a particular throughline or as a study of elements included in the installation from the point of view of the author.

1 Derived from Middle English limnur, indicating in the fourteenth century an illuminator of manuscripts, the term limner came, in the sixteenth century, to be associated with the leisurely production of watercolor-on-vellum miniatures. By the 1570s limnings were a popular form of recreational portraiture in England, exempt from the control of the guild of the Painter-stainers Company. Limnings, as miniature portraits, arrived in the colonies of New England before the invention of the mezzotint engraving technique and were one of the only media for the transatlantic transmission of portraiture for reproduction at this time. Limnings emphasized details of costume and facial features, contributing to the development of early New England portrait styles and a particular sense of what was desirable in the depiction of faces.

2 No relation. The author’s last name, itself a result of American modes of reproduction, was recorded (and created) at Ellis Island in the first decade of the twentieth century, from a Persian surname of unknown spelling and pronunciation.

3 “Photography is very nice, but better not to say so.”