In advance of the launch of Triple Canopy's new online publishing platform in September, we're posting some thoughts on the development of the magazine in the past few years and on our efforts to capitalize on the convergences of the Internet and IRL.

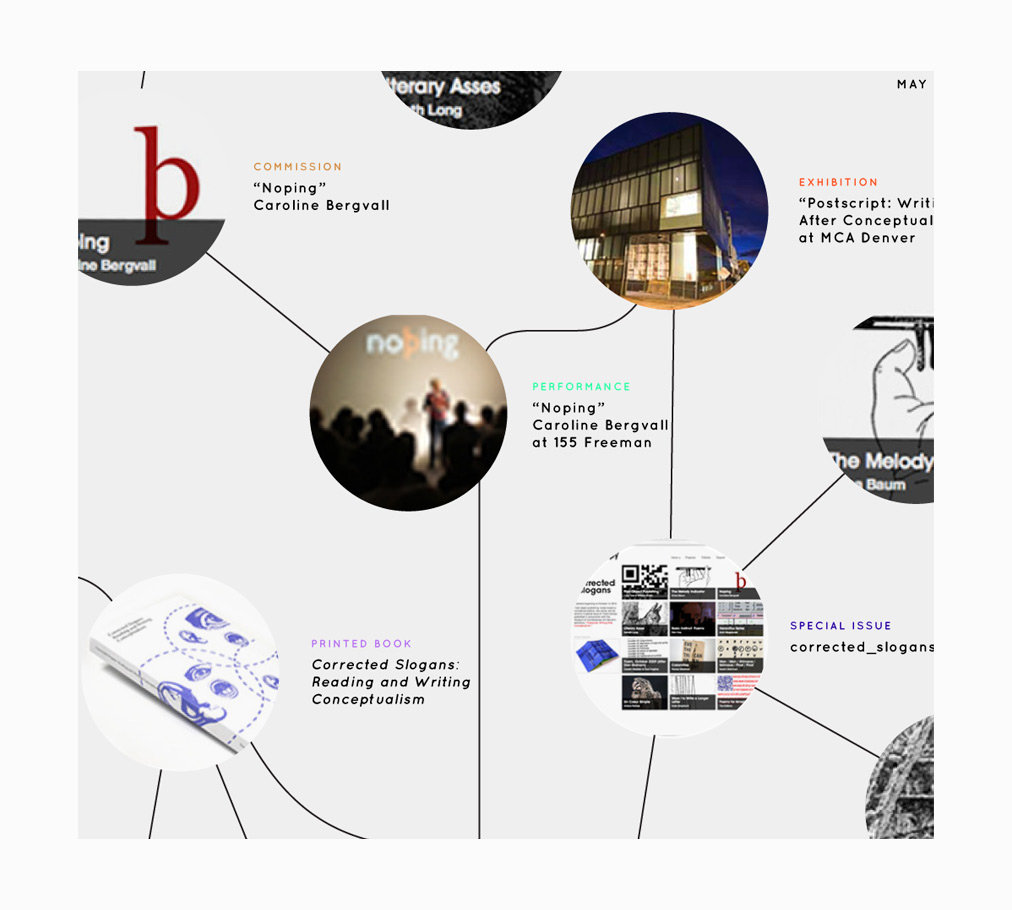

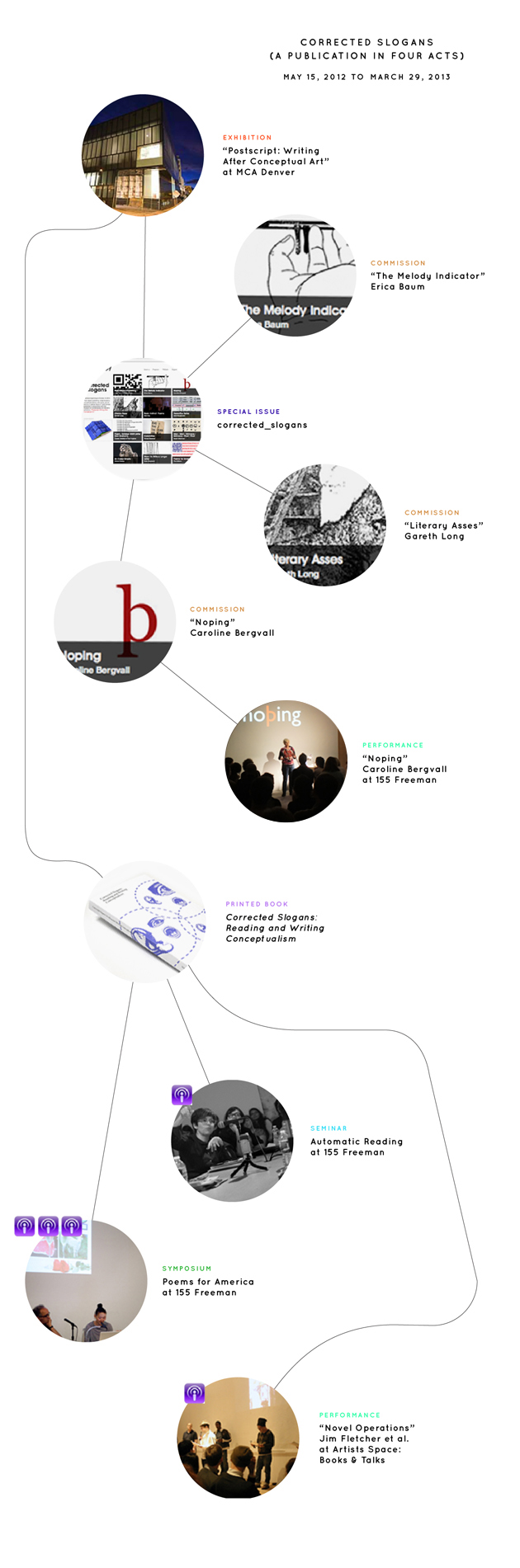

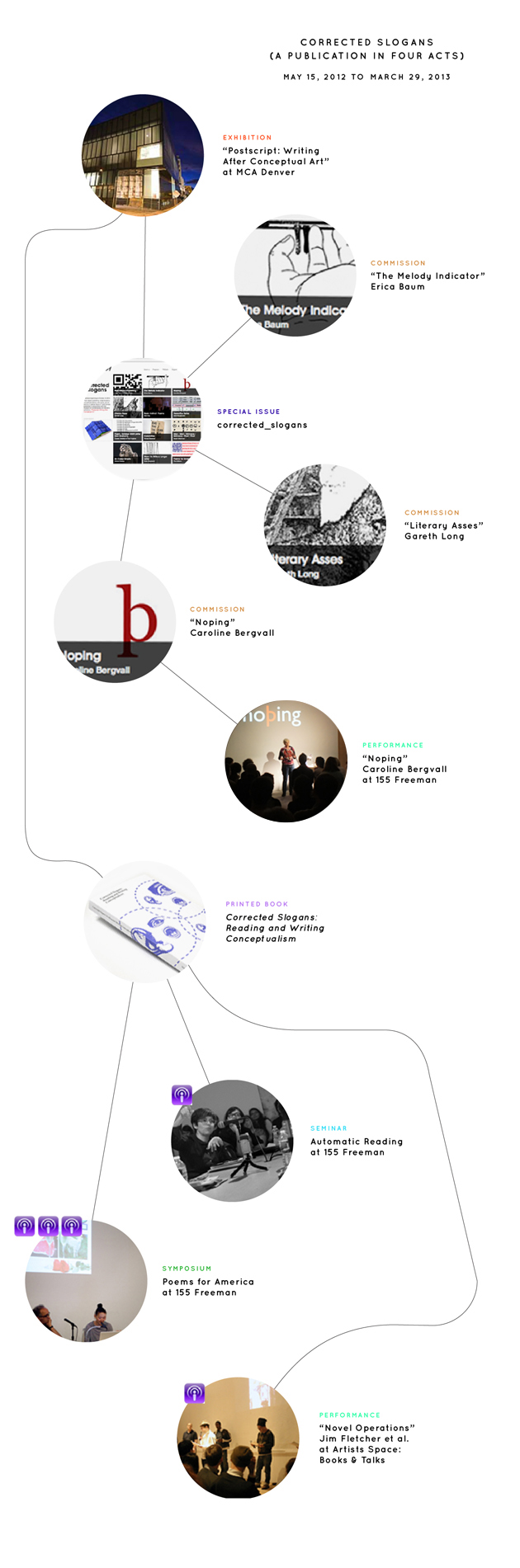

Diagram of Triple Canopy's Corrected Slogans (A Publication in Four Acts) project, 2012–13.

Diagram of Triple Canopy's Corrected Slogans (A Publication in Four Acts) project, 2012–13.

What is an online magazine? For a long time we defined Triple Canopy with that phrase: We started Triple Canopy five years ago because so many of us were increasingly encountering art and literature first, if not exclusively, online. And yet we could name very few places on the Web where we could have meaningful experiences with art and literature. As Triple Canopy evolved, we started to think of the online magazine as the hub of what we refer to as an “expanded field of publication,” which encompasses, so far, books, artist editions, public conversations, and technological experiments. Essentially, we’re annexing media, places, and activities not conventionally associated with the magazine, reconfiguring them as sites of publication—through a website illustrating and reinforcing the relationships between these forms and their audiences.

For the past year, as we’ve worked on redesigning our online platform and rethinking our approach to publishing, we’ve been asking how and why Triple Canopy is still a magazine. It’s a good descriptor for us in a certain sense: We are a magazine in that we publish content serially, an online magazine in that most of our work is presented online. Additionally, though pieces are by many authors they share a clear editorial sensibility. We don’t charge for access, though we do allow people to subscribe. We’re perhaps more like a journal in that most of our content isn’t time-sensitive: If you don’t read an essay or view an artist project this month, you can probably read it three months from now with little loss.

In other ways what we’re doing isn’t particularly magazine-like—or even online—at all. We organize public programs at our space in Greenpoint regularly; we participate in exhibitions like the current "EXPO 1: New York" via what might be called discursive projects; we put on, and occasionally participate in, shows at galleries; we teach classes and initiate educational workshops in cities like Chicago, New Orleans, Dallas, Berlin, and Sarajevo; we publish books, print as well as electronic.

And so “online magazine” starts to seem like a confusing rubric under which to hang what Triple Canopy does. Better add some awkward slashes: online magazine/editorial collective/exhibition space/curatorial platform. No—what we’d rather do is redefine what a magazine can be, and what publication means.

1.

The next iteration of Triple Canopy, due to launch in September, is, of course, a website, but we’re thinking of it as a publishing platform, since it will significantly impact how Triple Canopy’s activities online and offline are represented and related to one another. And so with what we’re calling Triple Canopy 3.0 we’d like to redefine the project—not as an online magazine, but as a magazine that incorporates publishing activities—that take place on the Web, in print, and in face-to-face conversations—and connects their respective audiences. In part, this is because we see the distinction between the Internet and real life diminishing rapidly, dramatically; the Internet is—or fundamentally conditions—real life, and vice versa. This notion of the Internet absolutely pervading our physical, lived experience is, of course, terrifying—unless you’ve always dreamed of the Singularity. But it's also an opportunity. Where we used to think about intersections between the Web and real life, and so online and offline activities, we can now, rather, just think of the world. While we used to invoke the slogan Slow down the Internet, now we’re moving on to the more apt, if more comical, Slow down the world.

With 3.0, the publishing platform will be Web-specific, while the magazine will be medium-agnostic. The slowness will be less specifically about one’s engagement with the screen, more about one’s engagement with culture. As John Dewey said: “Culture is also something personal; it is cultivation with respect to the appreciation of ideas and art and broad human interests. When efficiency is identified with a narrow range of acts, instead of with the spirit and meaning of activity, culture is opposed to efficiency.” (We used this quote in an essay pushing our campaign to raise the funds for 3.0; you can read—and, until July 1st, contribute!—here.) Thinking about designing a website in this way may seem overly complicated, or even self-important—and yet it pushes us to ask fundamental questions about how and why we might build a platform for the slow, meticulous work we want to do, the relationships we want to have, the thinking we want to do; how and why we might build something that looks more like the world we want to live in. We want to rethink, from the ground up, how we create culture and a coherent body of knowledge in a resistant, efficient, particularized world. And we want to keep enlarging our own sense of what Dewey called “the unity or integrity of experience.”

Let’s think about this in the somewhat mundane terms of our website architecture. Before, you could think of Triple Canopy’s issues as big clumps living in our database; we’re moving to a model where individual articles live in the database while a dynamic front-end system enables editors to connect them together on the fly in new configurations. For TC 3.0, we’re also completely redesigning our back-end database system to allow for a greater variety of content formats and a more flexible mechanism for relating and contextualizing content. Currently magazine pieces can only appear in issues, and so we’re limited by that one mode of visual display, that one mechanism for contextualizing and presenting our work. Our new backend system is being designed on the principle that we should be able to easily create and experiment with alternatives to the “issue.” Rather than hard-code organizational principles into the database, we’re creating a lightweight and flexible system that will facilitate experimentation and collaboration with partners such as the design studio Astrom/Zimmer, with whom we’ve been working for the past several months. To put this in slightly more technical terms, we’re putting an API at the heart of 3.0 in order to ease the development of alternative navigational experiences.

Lastly, our new database architecture will treat the range of Triple Canopy’s production in a more uniform manner. Instead of privileging pieces and issues, the records associated with podcasts, events, print publications, and other work will be treated as equal—materials that can be editorially situated, curated, contextualized, and re-contextualized using our flexible system. What does this mean? In the past, the form of the magazine was dictated by technology. Now it can be shaped—and reshaped, as the need arises—by the editors.

2.

As reading and viewing online have evolved in the past five years, so must Triple Canopy. Our current website represents Triple Canopy as an online magazine first and foremost, and fails to show (much less make an argument for) the relationships between the organization’s various publishing activities. Additionally, the website pushes all kinds of content into one format, the column-based system of Horizonize. We need a platform that forges meaningful, intuitive connections between print publications and live programming, between current goings-on and our ample archive; that shows the publication to be a networked object.

One aspect of Triple Canopy that’s played an increasingly significant role in the past few years is public discussions, talks, performances, and so on, whether at our space in Greenpoint or elsewhere. Some of these are spun from pieces that start in the magazine, others—including our annual marathon reading of Gertrude Stein’s The Making of Americans—are not so explicitly connected with an issue or article in the magazine, though the thematic connections are profound. So if people think of—and we treat—the magazine primarily in terms of issues and articles, such activities tend to fall through the cracks. The same goes for podcasts, print publications, annotations (shorter pieces that tend to be ancillary to longer pieces), special projects, exhibitions, and so on.

A major example is the recent project Corrected Slogans (A Publication in Four Acts). Corrected Slogans began as part of an exhibition at the Denver Museum of Contemporary Art called “Postscript: Writing after Conceptual Art.” The curators approached Triple Canopy in the fall of 2011, and it wasn’t quite clear if Triple Canopy was to be regarded as a co-publisher, an online annex, or an artist contributing to the show. Initially, we proposed to work with three artists in the show to produce projects for the magazine that might later be folded into a special issue; perhaps we’d produce a broadsheet for the exhibition, or perhaps we’d produce an iterative publication that would change the gallery space over time. Eventually, we organized a series of public conversations and performances in Greenpoint (all of which are available as podcasts). We then turned the conversations into an extensively annotated book (including projects specially commissioned for the printed page) that we envisioned as a critical commentary and enactment of the literary and artistic practices considered by the exhibition. We celebrated the publication with a live, scripted performance of the book at Artists Space.

How does all of this fit together? This project calls to mind Mallarmé’s statement that “everything exists to end in a book.” But there’s a structural downside: You could have come to all the Corrected Slogans events without really knowing about the online content. If you’re following us online, you might have noticed the related new works we published. And if you didn’t attend the Denver show, you might not know about the special issue of the magazine.

There’s an organizational problem: If you go to our site, you can find a lot of content related to Corrected Slogans: articles, events, MP3s, the book. If you go to our Facebook page, you can see documentation of the events; if you scroll back to ancient history in our Twitter timeline, you can get a sense of what the conversations were like. But this material is all over the place, and so there’s no coherent representation of the project. (This testifies to the value of the printed book: as a bounded whole, it can sum up what happened, if not fully represent the experience.) One of the problems we’re addressing in 3.0 is the connections between pieces. We’re looking at smart ways to get not just from an article to another article in the issue but also to events related to that article, to small pieces that might be ancillary to the article, and to other related collections of content. If next year we decide to revisit Corrected Slogans, we want to be able to add to the project and make it understood how new work relates to old.

So with 3.0, a project like Corrected Slogans would be a coherent issue of the magazine, which would include online works, symposia, performances, podcasts, an exhibition, and a print publication. That issue might be published over the course of one year, enabling one contributor to respond to another, and enabling readers to track the progress of a conversation as it progresses from one form to another over time. Simultaneously, we might be publishing another issue that lasts six months, and a third that lasts a year and a half—giving us the time to conduct research, build relationships with contributors, present our work to multiple audiences, and represent this dynamic process as essential to our concept of the magazine. Events will exist alongside articles. In 3.0, a public discussion becomes not only an event, but also an instance of publication that spans sites, times, audiences; a way of productively stitching together the Internet and the real world.

3.

When Triple Canopy started five years ago, it was hard to get people to spend a substantial amount of time reading on a screen. Phones were still dumb, the audience on tablets was infinitesimal. That’s all changed. Initially, we made an argument that serious reading and viewing could be done online. Our design was based on that idea: If a magazine were impeccably designed for the medium it inhabits, people would want to spend time with it. The situation now is more complex: People are reading on many different kinds of screens, for long periods of time, and massive amounts of money have gone into facilitating this. To some degree, rather than directing people how to read, we need to accommodate their existing (and still fluctuating) reading practices.

A second design requirement becomes apparent with time: sustainability. The majority of the pieces that we’ve published in the past five years are still interesting and relevant; as I mentioned earlier, our content becomes dated relatively slowly, if at all. The design challenge now is to construct a system in which our content remains legible, or even becomes more engaging by acquiring a context, over time.

Sometimes the problem happens on a banal level: Videos embedded using Flash don’t work if you’re on an iPad. If you’re using YouTube to embed a video, you can get past Flash, but you might get stuck if the video gets pulled because of copyright claims. Web standards have stabilized, so this problem can be solved now, but it still requires a lot of work. A more complex job is making a content creation tool that allows editors to create works that function—and maintain the integrity of their design—in many different formats. What we’re concentrating on now is creating an editing environment that allows for the simple creation of rich media for multiple platforms, and which degrades intelligently. Rather than dictate the experience of readers, we’ll establish self-adjusting templates for work appearing on a Kindle, a phone, a tablet, or even print.

4.

In sum, Triple Canopy’s attention to emerging artistic practices (and the modes of reading and viewing they engender) has led to innovative formats that accommodate long-form writing, intermedia artwork, and experimental publications—many of which are now common on the Web. TC 3.0 will work toward a particular paradigm for screen-reading, but will pay careful attention to the visual and typographic tropes that have endured in classic general-interest magazines for 150 years. Rather than mimic the standards created by tablet devices that, to our minds, are less about reading than about packaging, monetizing, and circulating content, we’re trying to innovate on our own terms. The code underlying 3.0 will be made available as an open-source application; we hope this will be an important contribution to the progressive design community.

What we’re trying to do with Triple Canopy 3.0 doesn’t quite resemble what people usually think of when they think of magazines, much less online magazines. Rather, it’s a publication space that works to incorporate the rest of the world—just as the Internet can no longer be distinguished from the world we inhabit. A magazine brings writers and readers together, and we’re going to continue to do that, both online and off.

Diagram of Triple Canopy's Corrected Slogans (A Publication in Four Acts) project, 2012–13.

Diagram of Triple Canopy's Corrected Slogans (A Publication in Four Acts) project, 2012–13.

What is an online magazine? For a long time we defined Triple Canopy with that phrase: We started Triple Canopy five years ago because so many of us were increasingly encountering art and literature first, if not exclusively, online. And yet we could name very few places on the Web where we could have meaningful experiences with art and literature. As Triple Canopy evolved, we started to think of the online magazine as the hub of what we refer to as an “expanded field of publication,” which encompasses, so far, books, artist editions, public conversations, and technological experiments. Essentially, we’re annexing media, places, and activities not conventionally associated with the magazine, reconfiguring them as sites of publication—through a website illustrating and reinforcing the relationships between these forms and their audiences.

For the past year, as we’ve worked on redesigning our online platform and rethinking our approach to publishing, we’ve been asking how and why Triple Canopy is still a magazine. It’s a good descriptor for us in a certain sense: We are a magazine in that we publish content serially, an online magazine in that most of our work is presented online. Additionally, though pieces are by many authors they share a clear editorial sensibility. We don’t charge for access, though we do allow people to subscribe. We’re perhaps more like a journal in that most of our content isn’t time-sensitive: If you don’t read an essay or view an artist project this month, you can probably read it three months from now with little loss.

In other ways what we’re doing isn’t particularly magazine-like—or even online—at all. We organize public programs at our space in Greenpoint regularly; we participate in exhibitions like the current "EXPO 1: New York" via what might be called discursive projects; we put on, and occasionally participate in, shows at galleries; we teach classes and initiate educational workshops in cities like Chicago, New Orleans, Dallas, Berlin, and Sarajevo; we publish books, print as well as electronic.

And so “online magazine” starts to seem like a confusing rubric under which to hang what Triple Canopy does. Better add some awkward slashes: online magazine/editorial collective/exhibition space/curatorial platform. No—what we’d rather do is redefine what a magazine can be, and what publication means.

1.

The next iteration of Triple Canopy, due to launch in September, is, of course, a website, but we’re thinking of it as a publishing platform, since it will significantly impact how Triple Canopy’s activities online and offline are represented and related to one another. And so with what we’re calling Triple Canopy 3.0 we’d like to redefine the project—not as an online magazine, but as a magazine that incorporates publishing activities—that take place on the Web, in print, and in face-to-face conversations—and connects their respective audiences. In part, this is because we see the distinction between the Internet and real life diminishing rapidly, dramatically; the Internet is—or fundamentally conditions—real life, and vice versa. This notion of the Internet absolutely pervading our physical, lived experience is, of course, terrifying—unless you’ve always dreamed of the Singularity. But it's also an opportunity. Where we used to think about intersections between the Web and real life, and so online and offline activities, we can now, rather, just think of the world. While we used to invoke the slogan Slow down the Internet, now we’re moving on to the more apt, if more comical, Slow down the world.

With 3.0, the publishing platform will be Web-specific, while the magazine will be medium-agnostic. The slowness will be less specifically about one’s engagement with the screen, more about one’s engagement with culture. As John Dewey said: “Culture is also something personal; it is cultivation with respect to the appreciation of ideas and art and broad human interests. When efficiency is identified with a narrow range of acts, instead of with the spirit and meaning of activity, culture is opposed to efficiency.” (We used this quote in an essay pushing our campaign to raise the funds for 3.0; you can read—and, until July 1st, contribute!—here.) Thinking about designing a website in this way may seem overly complicated, or even self-important—and yet it pushes us to ask fundamental questions about how and why we might build a platform for the slow, meticulous work we want to do, the relationships we want to have, the thinking we want to do; how and why we might build something that looks more like the world we want to live in. We want to rethink, from the ground up, how we create culture and a coherent body of knowledge in a resistant, efficient, particularized world. And we want to keep enlarging our own sense of what Dewey called “the unity or integrity of experience.”

Let’s think about this in the somewhat mundane terms of our website architecture. Before, you could think of Triple Canopy’s issues as big clumps living in our database; we’re moving to a model where individual articles live in the database while a dynamic front-end system enables editors to connect them together on the fly in new configurations. For TC 3.0, we’re also completely redesigning our back-end database system to allow for a greater variety of content formats and a more flexible mechanism for relating and contextualizing content. Currently magazine pieces can only appear in issues, and so we’re limited by that one mode of visual display, that one mechanism for contextualizing and presenting our work. Our new backend system is being designed on the principle that we should be able to easily create and experiment with alternatives to the “issue.” Rather than hard-code organizational principles into the database, we’re creating a lightweight and flexible system that will facilitate experimentation and collaboration with partners such as the design studio Astrom/Zimmer, with whom we’ve been working for the past several months. To put this in slightly more technical terms, we’re putting an API at the heart of 3.0 in order to ease the development of alternative navigational experiences.

Lastly, our new database architecture will treat the range of Triple Canopy’s production in a more uniform manner. Instead of privileging pieces and issues, the records associated with podcasts, events, print publications, and other work will be treated as equal—materials that can be editorially situated, curated, contextualized, and re-contextualized using our flexible system. What does this mean? In the past, the form of the magazine was dictated by technology. Now it can be shaped—and reshaped, as the need arises—by the editors.

2.

As reading and viewing online have evolved in the past five years, so must Triple Canopy. Our current website represents Triple Canopy as an online magazine first and foremost, and fails to show (much less make an argument for) the relationships between the organization’s various publishing activities. Additionally, the website pushes all kinds of content into one format, the column-based system of Horizonize. We need a platform that forges meaningful, intuitive connections between print publications and live programming, between current goings-on and our ample archive; that shows the publication to be a networked object.

One aspect of Triple Canopy that’s played an increasingly significant role in the past few years is public discussions, talks, performances, and so on, whether at our space in Greenpoint or elsewhere. Some of these are spun from pieces that start in the magazine, others—including our annual marathon reading of Gertrude Stein’s The Making of Americans—are not so explicitly connected with an issue or article in the magazine, though the thematic connections are profound. So if people think of—and we treat—the magazine primarily in terms of issues and articles, such activities tend to fall through the cracks. The same goes for podcasts, print publications, annotations (shorter pieces that tend to be ancillary to longer pieces), special projects, exhibitions, and so on.

A major example is the recent project Corrected Slogans (A Publication in Four Acts). Corrected Slogans began as part of an exhibition at the Denver Museum of Contemporary Art called “Postscript: Writing after Conceptual Art.” The curators approached Triple Canopy in the fall of 2011, and it wasn’t quite clear if Triple Canopy was to be regarded as a co-publisher, an online annex, or an artist contributing to the show. Initially, we proposed to work with three artists in the show to produce projects for the magazine that might later be folded into a special issue; perhaps we’d produce a broadsheet for the exhibition, or perhaps we’d produce an iterative publication that would change the gallery space over time. Eventually, we organized a series of public conversations and performances in Greenpoint (all of which are available as podcasts). We then turned the conversations into an extensively annotated book (including projects specially commissioned for the printed page) that we envisioned as a critical commentary and enactment of the literary and artistic practices considered by the exhibition. We celebrated the publication with a live, scripted performance of the book at Artists Space.

How does all of this fit together? This project calls to mind Mallarmé’s statement that “everything exists to end in a book.” But there’s a structural downside: You could have come to all the Corrected Slogans events without really knowing about the online content. If you’re following us online, you might have noticed the related new works we published. And if you didn’t attend the Denver show, you might not know about the special issue of the magazine.

There’s an organizational problem: If you go to our site, you can find a lot of content related to Corrected Slogans: articles, events, MP3s, the book. If you go to our Facebook page, you can see documentation of the events; if you scroll back to ancient history in our Twitter timeline, you can get a sense of what the conversations were like. But this material is all over the place, and so there’s no coherent representation of the project. (This testifies to the value of the printed book: as a bounded whole, it can sum up what happened, if not fully represent the experience.) One of the problems we’re addressing in 3.0 is the connections between pieces. We’re looking at smart ways to get not just from an article to another article in the issue but also to events related to that article, to small pieces that might be ancillary to the article, and to other related collections of content. If next year we decide to revisit Corrected Slogans, we want to be able to add to the project and make it understood how new work relates to old.

So with 3.0, a project like Corrected Slogans would be a coherent issue of the magazine, which would include online works, symposia, performances, podcasts, an exhibition, and a print publication. That issue might be published over the course of one year, enabling one contributor to respond to another, and enabling readers to track the progress of a conversation as it progresses from one form to another over time. Simultaneously, we might be publishing another issue that lasts six months, and a third that lasts a year and a half—giving us the time to conduct research, build relationships with contributors, present our work to multiple audiences, and represent this dynamic process as essential to our concept of the magazine. Events will exist alongside articles. In 3.0, a public discussion becomes not only an event, but also an instance of publication that spans sites, times, audiences; a way of productively stitching together the Internet and the real world.

3.

When Triple Canopy started five years ago, it was hard to get people to spend a substantial amount of time reading on a screen. Phones were still dumb, the audience on tablets was infinitesimal. That’s all changed. Initially, we made an argument that serious reading and viewing could be done online. Our design was based on that idea: If a magazine were impeccably designed for the medium it inhabits, people would want to spend time with it. The situation now is more complex: People are reading on many different kinds of screens, for long periods of time, and massive amounts of money have gone into facilitating this. To some degree, rather than directing people how to read, we need to accommodate their existing (and still fluctuating) reading practices.

A second design requirement becomes apparent with time: sustainability. The majority of the pieces that we’ve published in the past five years are still interesting and relevant; as I mentioned earlier, our content becomes dated relatively slowly, if at all. The design challenge now is to construct a system in which our content remains legible, or even becomes more engaging by acquiring a context, over time.

Sometimes the problem happens on a banal level: Videos embedded using Flash don’t work if you’re on an iPad. If you’re using YouTube to embed a video, you can get past Flash, but you might get stuck if the video gets pulled because of copyright claims. Web standards have stabilized, so this problem can be solved now, but it still requires a lot of work. A more complex job is making a content creation tool that allows editors to create works that function—and maintain the integrity of their design—in many different formats. What we’re concentrating on now is creating an editing environment that allows for the simple creation of rich media for multiple platforms, and which degrades intelligently. Rather than dictate the experience of readers, we’ll establish self-adjusting templates for work appearing on a Kindle, a phone, a tablet, or even print.

4.

In sum, Triple Canopy’s attention to emerging artistic practices (and the modes of reading and viewing they engender) has led to innovative formats that accommodate long-form writing, intermedia artwork, and experimental publications—many of which are now common on the Web. TC 3.0 will work toward a particular paradigm for screen-reading, but will pay careful attention to the visual and typographic tropes that have endured in classic general-interest magazines for 150 years. Rather than mimic the standards created by tablet devices that, to our minds, are less about reading than about packaging, monetizing, and circulating content, we’re trying to innovate on our own terms. The code underlying 3.0 will be made available as an open-source application; we hope this will be an important contribution to the progressive design community.

What we’re trying to do with Triple Canopy 3.0 doesn’t quite resemble what people usually think of when they think of magazines, much less online magazines. Rather, it’s a publication space that works to incorporate the rest of the world—just as the Internet can no longer be distinguished from the world we inhabit. A magazine brings writers and readers together, and we’re going to continue to do that, both online and off.