Imagine an electronic book whose functions are so seamlessly resolved that its sheer, undeniable academic utility effectively curtails the uneasy tittering rippling through the halls of cultural institutions fearful of digitization. At the opening session of this year’s Museums and the Web conference, held in Philadelphia in April, digital futurists and doubting Thomases alike were treated to a preview of what may be just such a thing. In a packed session on e-books and Museum Publishing moderated by Dana Mitroff-Silvers of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Nik Honeysett, Head of Administration at the J. Paul Getty Foundation, introduced the crowd of technologists, content strategists, and otherwise concerned museumfolk to the Online Scholarly Catalogue Initiative (OSCI), a five-year, multimillion dollar project designed to help museums transition from print to digital publishing. Eight museums—the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Art Institute of Chicago, Seattle Art Museum, the Tate, the Walker Art Center, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Smithsonian Institution, and the National Gallery of Art —are currently using two-year planning grants to chart their digital futures. And making PDF versions of books available to the public, the most common strategy for resource-strapped institutions, will not suffice; the OSCI mandate pushes museums to make catalogues that are native to the digital realm.

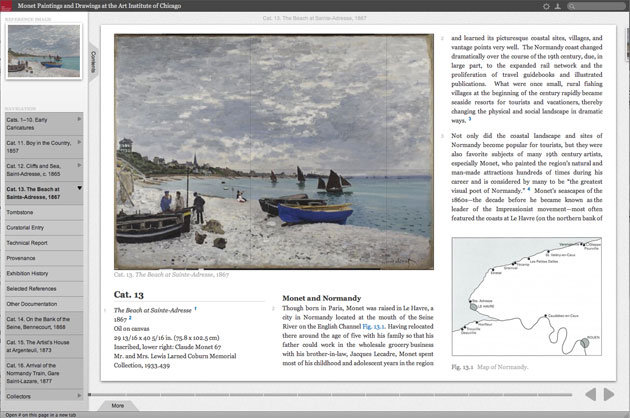

Historically, the museum catalogue has occupied multiple positions of authority, as the archival document of a physical exhibition, a scholarly resource, and a symbol of institutional prestige. The latter proves exceptionally difficult to do away with: Curators and museum directors really love catalogues (and seeing their names on and in those catalogues). Honeysett referred to this material preciousness as “the boom effect,” mimicking the satisfactory thud of a heavy book’s sudden closure. Of course, many technologists also love catalogues. The advent of tablet computing will not entirely supplant print,, especially in art history, which draws on a long tradition of bookmaking. This much was evident in the presentation given by Sam Quigley and Elizabeth Neely, from the Art Institute of Chicago, detailing their OSCI project, a digital catalogue of forty-nine paintings and twenty-three drawings by Monet and Renoir from the museum’s collection.

Quigley’s account of developing cross-departmental workflows for the project—“Museum registrars organize information in ways that are a mystery—even to them!”—drew audible (yet affable) groans from the audience, whose members were well versed in the perils of institutional collaboration. His talk extended beyond the anecdotal to acknowledge the deeper philosophical and practical differences that exist between museum departments, and how negotiating between them becomes as much a part of an agile development process as the end product itself—a practical insight that should prove invaluable to those similarly charged. The Art Institute will be the first to deliver the fruits of such labors, as it is scheduled to launch an official preview of its online interface for the catalogue, which is being designed in collaboration with the IMA Lab at the Indianopolis Museum of Art, in October.

As was to be expected, considering the IMA Lab’s prime position in the field, the interface looked good. Very good. Neely’s excitement was palpable as she guided the audience through the prototype, whose functional design is evidently tailored to the needs of image-sensitive, research-oriented readers. There are nods to academic reading habits, such as zoomable images, text highlighting, tagged notes, and citation markers. Similarly, other features not only mimic the way we physically interact with books as objects but, in some cases, advance our engagement with texts and images. The “wow” factor is key here; the design-and-usability dog-and-pony show inspired audience members to grapple for their iPhones to dispatch screen shots of Neely’s slide show. But in order for electronic publishing to truly take hold within cultural institutions, skeptics must find the digital reading experience not only delightful, but as much (if not more) practically useful than its print counterpart. E-books need to be valued as discrete reading experiences, not mere toys or supplements to print editions. Though it has years to go, the OSCI project is clearly pushing e-book publishing (and the perception of it among institutions) in that direction. But business models around cost, copyright, and distribution are still under development, and they are, shall we say, device-agnostic.