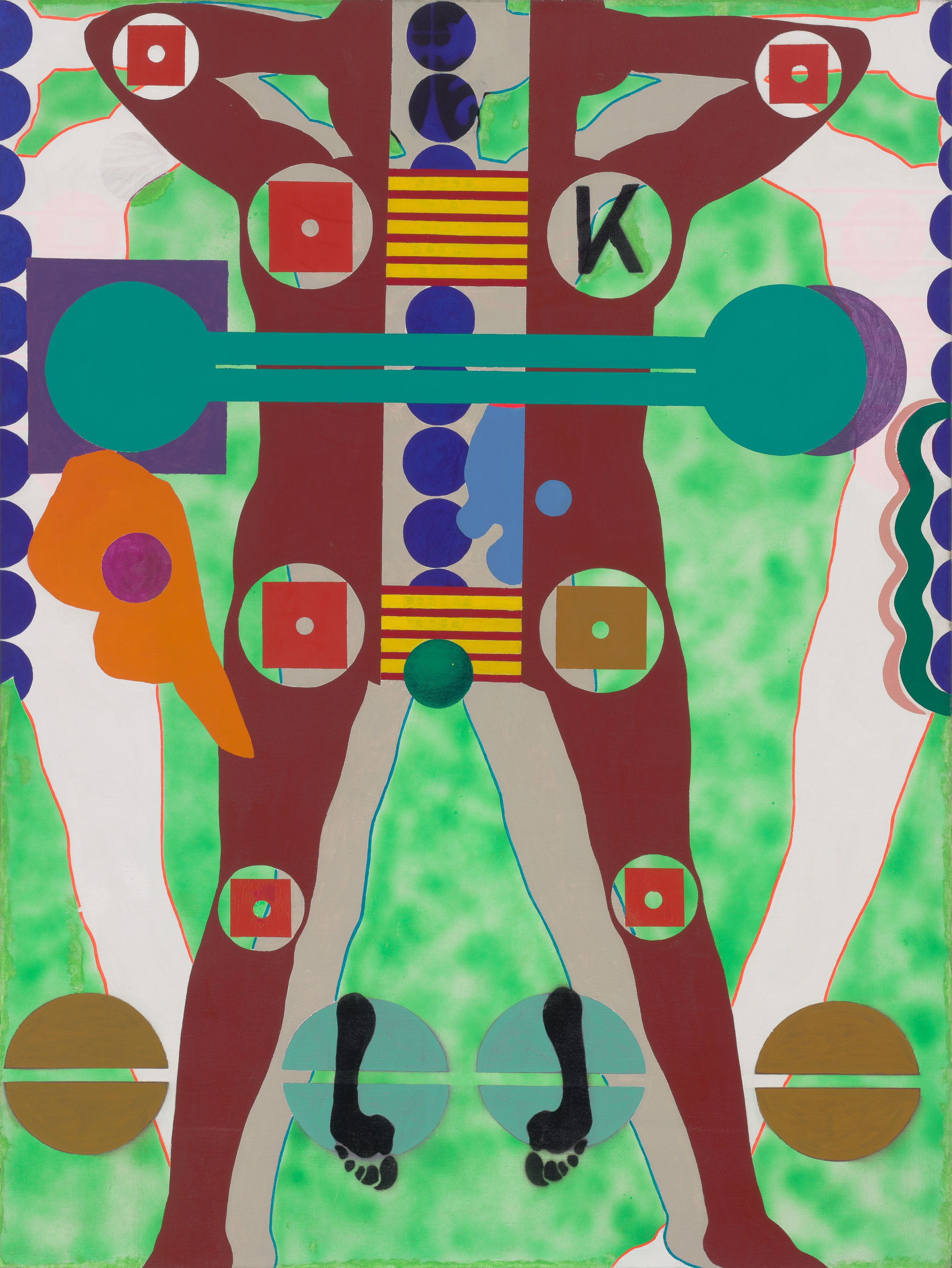

Detail, in grayscale, from Kiki Kogelnik, Outer Space, 1964, oil and acrylic on canvas, 72" × 54". All images in “Illness as Festival” are courtesy of the Kiki Kogelnik Foundation, which holds the copyrights. Thanks to Simone Subal Gallery, which represents Kogelnik’s estate.

Are we our illnesses? At the Aspen Ideas Festival, thought leaders gather under the Koch Tent to pursue a “culture of health.” An essay on the kingdom of the sick in the age of biotech.

Incomprehensibility has an enormous impact over us in illness, more legitimately perhaps than the upright will allow.

–Virginia Woolf, “On Being Ill,” 1926

1.

One of the first things I overheard upon arriving in Aspen last summer was that the billionaires are pushing out the millionaires. I had flown to Colorado for Spotlight Health, the fourth annual precursor to the Aspen Ideas Festival, a ten-day-long convocation billed as the premier summit for global thought leaders who are tackling the issues that “shape our lives and challenge our times”—think of a stateside, warm-weather analogue to the World Economic Forum’s yearly Davos meetup. The opening ceremony was held beneath a large white tent, one of a handful sailing across the expansive Aspen Institute campus, which, at midsummer, is a lush Bauhausian idyll, ringed by a corona of snowcapped peaks and forested ridges that gleam with multimillion-dollar homes. Walter Isaacson, the perennially best-selling biographer and genial Ideas Festival founder, on the cusp of retiring as president and CEO of the Aspen Institute, welcomed an audience of hundreds. “Spotlight Health is about every decision we make about wellness and health care,” he said. A brief and jaunty video then played across a jumbo screen, urging each of us to “give your whole body and mind over to this experience.”

Who are we, I wondered, as I took in the immaculate grid of white folding chairs, occupied by conservatively dressed, amped-up people with the air of coworkers on a boozy lunch break. I found a seat between a row reserved for the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and another saved for Pfizer, festival underwriters both, and made note of RWJ’s sanguine motto: “Building a Culture of Health.” A ten-minute creekside stroll away was the Koch Tent, named for David and pitched on the lawn of the modernist building bearing his name. Many of the main-stage panels were held in Koch’s tent: The Neuroscience of Poverty, The Opioid Tsunami, A World Without AIDS, and Race Disparities and Health Outcomes. I attended a conversation in the Koch Building about the effect of environmental toxins on children, and felt a pulse of relief when the moderator, the president and CEO of Mt. Sinai, Kenneth L. Davis, paused mid-discussion to note the irony of the locale.

According to the promotional literature, the three-day conference, first held in 2014 and cosponsored by the Atlantic, is a haven for “deep thinkers, innovative doers, determined entrepreneurs, brilliant scientists, and artists on a social mission.” They were there to think big (and court funding). Entrance ran two thousand dollars. As I signed in at the press desk I glanced around the registration tent, sussing out the cross section of people, glimpsing altruism’s meandering path through philanthropy. My teal press pass was a similar shade to those of paying attendees and the hundred-strong Scholars, who were sponsored by yellow-tagged Patrons. The Patrons, in fine linens and wide-brimmed hats, maintained a dewiness of the skin despite the high-altitude heat, a feat that mystified and annoyed me. I met a Walton, whose family—the wealthiest in the country, with a net worth of $130 billion, thanks to Walmart—had financed the unlimited use of municipal bicycles for Ideas Festival attendees to ride around town. I met a number of young doctors whose continuing medical education funds paid their fares.

Many attendees were brought by their festival-sponsoring employers. A low-key philanthropy adviser for a Manhattan-based foundation, who went to college with an editor of a Brooklyn literary magazine and so claimed familiarity with my milieu, compulsively commented on the displays of wealth in Aspen. He could not believe that the hotel where his boss had put him up offered loaner Mercedes Benzes for guests. “It’s even ritzier than Jackson Hole,” he marveled on the shuttle to an off-campus event one day. We twice encountered each other at the healthy-snacks tent, helping ourselves to chili-dusted pistachios and bottles of pomegranate juice, which were kept in a cooler shaped like a bottle of pomegranate juice. The volume, quality, and variety of complimentary lunch options was orgiastic yet nutritious, and served on compostable plates.

The intersection of conspicuous consumption and civil discourse was most directly articulated by the Atlantic’s editor in chief, Jeffrey Goldberg, during his closing-day interview of Health and Human Services secretary Tom Price, since disgraced for using taxpayer funds to travel by private jet, perhaps even to Aspen that very morning. “There is a guarantee that you come to the Aspen Institute and you get free food,” said Goldberg, as he tacitly underscored Price’s flimflam refusal to state on the record that a repeal of Obamacare would not lead to anyone on Medicaid being kicked out of a nursing home. “That’s the only guarantee that I know.”

2.

I suppose that something you understand implicitly when ill is that your health is always in relation to power. When I was finally diagnosed with cancer in 2013, after more than two years of ill health and countless tests, I had plenty of access to power. I had the power to seek diagnosis and care. I had the power to ask for the help of my friends, family, and employers. I had the power of being insured. But when I speak of illness in relation to power, I mean that as a sick person I felt completely at the mercy of interlocking behemoths that I couldn’t fully comprehend. I was at the mercy of medical expertise and conjecture, labyrinthine insurance companies, the United States Congress, and my own snowballing debt.

The years-long arc of my sickness has been marked by a sustained unknowing, which I can’t help but equate with powerlessness. I have grown familiar with, which is not to say accustomed to, the long beat between test and result. To the hours spent on hold, unsure whether this procedure or that prescription will be authorized. To the dogged self-advocacy that one must affect in order to navigate the miasma of the American health-care system. Having spent the past five years ruminating on all this—as a patient and as a writer—I was curious to see how my experiences might be filtered through a forum populated by researchers and doctors, policy makers and philanthropists. People, in other words, whose expertise and influence have shaped the contours of my ordeal.

At Spotlight Health, I imagined, I would sidle up to clout and demystify the “medical-industrial complex”—that imbroglio of healing and profit—that I feel at once grateful for and subjected to. I went to Aspen to reconstitute myself with external knowledge; to press illness through the sieve of clinical language, longitudinal research, biostatistics, disruptive schemes. I wanted to subject my personal story to an ad hoc political analysis. I wanted to comprehend illness from outside it, which is to say from beyond being sick.

I agree with Susan Sontag’s misgivings in Illness as Metaphor (1978) about cancer being in any way related to personal fault, a lack of will, or a deficit of temperament. I get why Sontag argues against metaphor as a means of understanding sickness. She wants to deprive illness of romanticized meaning, facile interpretation. I, too, am exasperated by the still-ubiquitous reliance on the language of warfare to denote the realities of fighting cancer. Like so many people, I am living with cancer as a chronic condition that I will monitor and regulate for the rest of my days. Cancer, in this sense, can be thought of not as an invading army, but as an expression of one’s self.

I am fond of a phrase from the artist and writer Catherine Lord’s formidable memoir The Summer of Her Baldness: A Cancer Improvisation (2004). Lord writes, “Illness is not something that happens to you but something that you are.” I am troubled and relieved by this statement, which seems to me both corollary and counterpoint to Sontag’s assertion that “everyone who is born holds dual citizenship, in the kingdom of the well and in the kingdom of the sick,” and eventually takes up residence in the latter. With the advent of research confirming that our brains, epigenetic processes, and immune systems are affected by our environments and experiences—our zip codes and our traumas—is the argument against metaphor beside the point? What are the implications of conceiving of our illnesses as literal expressions of who we are?

3.

Some facts that were dispensed to me in Aspen: Medicaid is the largest source of federal money for every state. The average annual income for home caregivers is thirteen thousand dollars per year. Until Obama changed the law in 2016, home health workers were excluded from the Fair Labor Standards Act because New Deal–era senators wouldn’t pass a bill that included farm and home-care workers, who were predominantly African American. Women physicians in the United States have a 130 percent higher suicide rate than women in the general population. No one in the Global South has access to PrEP, which can prevent the contraction of HIV, and only 10 percent of those in the United States who would benefit from PrEP are on the drug. The YMCA now has a diabetes program supported by Medicaid. An unintended consequence of the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency in 1970 was the separation, on the federal level, of the environment and public health.

4.

One afternoon, I stood on a knoll at the center of campus and looked at some pieces of the AIDS Memorial Quilt that had been laid out on the grass. The day before, I had befriended the volunteer, Laura, charged with watching over the three-by-six-foot panels, which surely were fading under the midday sun. The first pieces of the ongoing quilt—now described as the largest community art project in the world—were sewn in San Francisco in 1987 to document the lives of people lost to AIDS, lives that the quilt’s founder, the gay-rights activist Cleve Jones, feared would be forgotten. As a child in suburban Los Angeles in the 1980s, I first really comprehended the AIDS pandemic when some panels were displayed in my elementary school cafeteria. Laura, an impassioned art therapist from a small town outside Aspen, confessed that she felt ill-equipped to represent the quilt, a task she clearly assumed with great reverence, an honor. She had one friend with AIDS, a man who lived three hours away in Boulder. She had gotten permission from the Aspen Institute for him to come on campus, stand with her, talk about the quilt and, I suppose, about living with AIDS.

“Did your friend make it?” I asked.

“No, he couldn’t get off work.”

A sweaty, middle-aged man in a baseball cap slowly walked the length of the panels, studiously pausing to bend over each one. Every few minutes he removed his hat, wiped his brow, and rested the hat on his heart.

“Do you have a favorite?” he asked me, without looking up.

I bit back a cringe and thought of something my friend Gregg Bordowitz—an artist, writer, and activist who has created an extensive, indispensable body of work about the AIDS crisis—once said to me, wryly: “Some of my best friends are quilts.”

Like Laura, the man in the baseball cap assumed the somber air of a museum visitor, a lapsed believer touring a grand and ancient church. We eyed each other’s name cards. He was a doctor from the West Los Angeles Veterans Administration, and he told me that when he began to practice, at the beginning of the epidemic, he worked in an AIDS unit. He was ashamed to admit that he had been so overwhelmed, so green, that he couldn’t see his patients as people. He didn’t get to know any of them personally, as he was consumed by the mystery and the gravity of their illness. Also, I inferred, he had been afraid. Now, having walked by the quilt on his way to the lunch tent, the doctor appeared to be reaching for some sort of atonement. He seemed startled and emotional, peering into the faces, patches, and handwritten notes that adorned the fabrics.

“They were so young,” he said.

We chatted for a few minutes, shielding our eyes from the sun. I told him about “G-9,” the long poem that Tim Dlugos wrote from the AIDS ward at Roosevelt Hospital in New York shortly before he died at age forty.

On Amsterdam,

pedestrians and drivers are

oblivious to our small aerie,

as we peer through the grille

like cloistered nuns. Since

leaving G-9 the first time,

I always slow my car down

on this block, and stare up

at this window, to the unit

where my life was saved.

The quilt was not the only forum for discussion of HIV/AIDS at the festival. I attended A World Without AIDS, a wide-ranging and, at times, contentious conversation between Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease; Jamila Headley, the managing director of Health Global Access Project; and Andrew Witty, who recently retired as the CEO of GlaxoSmithKline. The point of the Johnson & Johnson–sponsored panel was to discuss current research on a vaccine—“so that one day we can live in a world without AIDS.” But the panelists took pains to point out that a vaccine is a long way off and, meanwhile, there is infinite work to be done to counter the misperception that AIDS is under control, and to bridge the gap between scientific advancements and access to care.

“I was asked last year by a congressman at a budget hearing, You know, didn’t we solve this problem?” said Fauci, an immunologist. “Why do you have to have so much money in AIDS? Why don’t we just move it out into something else?”

I had taken note of Headley, whose organization pushes for global access to affordable HIV medicine, the previous evening. While being feted at a ceremony for the Aspen Institute’s New Voices Fellowship, she said that her advocacy always begins with the question, “Who has the power? We are aware that we need to move power.”

On the AIDS panel, she questioned the pharmaceutical industry’s claim that exorbitant drug prices are driven by the costs of research, development, and manufacturing. “I want to challenge the conventional wisdom that we have to have a model that even starts off with drugs at this price, causing slower access to drugs for people around the world.”

5.

“The gap here is the patients. Where are they in this conversation?” asked Melinda, a health conference director for the Canadian Medical Association, at the end of a heavy early afternoon panel called The Opioid Tsunami. Melinda happened to be on the folding chair next to mine in the Koch Tent. We hadn’t yet introduced ourselves, but I had given her some tissues when she was brought to tears by sensationally bleak footage from Perri Peltz’s documentary Warning: This Medication May Kill You. Melinda wasn’t complaining about a dearth of empathy or seriousness: Peltz was joined on the panel by Yasmin Hurd, a neurobiologist and addiction researcher; Nora Volkow, the longtime head of the National Institutes of Health’s drug and addiction task force; and Vivek Murthy, President Obama’s surgeon general. The “global health intelligentsia”—to use the writer Ariel Levy’s phrase—comprises people who have dedicated their lives to the health of others. Yet in Aspen they contemplated sick people, who putatively are the raison d’être of the festival, only in absentia.

Melinda’s tears, and her comment about who was glaringly missing, eased me from the detached reverie I had tried to assume as a reporter. Many of the people at Spotlight Health surely are or have been sick, but no one publicly identified that way. Not a single panel that I attended featured someone whose expertise was founded on, or had anything to do with, a personal experience of being ill. This seemed not just a lost opportunity, but also symptomatic of a pervasive habit of mind: the abstraction of the sick.

We all perform this quarantine. I had come to Spotlight Health with the hope of comprehending illness as separate from my own cancer; to supplant—or at least temper—my experience with a stupefying wash of impersonal information. I understand the impulse to isolate illness, whether as a temporary aberration in our personal lives or as a stroke of misfortune endured by others. To maintain that sickness is a kingdom apart from that of health is to suspend disbelief. Wouldn’t it be nice if every single one of us were not, at all times, vulnerable?

Of course, some are less vulnerable, or more able to mitigate their vulnerability, than others. The righteousness—and viability—of this situation was the subject of a debate on the first evening of the festival: Whither Health Care Reform? Andy Slavitt, who ran the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services under Obama, faced off against Lanhee Chen, a senior policy adviser to both the Romney and Rubio presidential campaigns. The moderator, PBS’s Judy Woodruff, asked “whether there’s a right to health care.”

Chen argued that health care is not a “fundamental right” like the right to basic education and the use of roads, and so should not be “guaranteed” by the government. “But I think that we need to do everything we can to make sure people have access to affordable health care,” he added.

Slavitt failed to see the difference. “We don’t guarantee everybody access to private schools” like Stanford, he observed. But the right to basic education seems as fundamental as the right of “people who have sick family members” to “not go bankrupt as a result.”

Chen opined that the problem is “a health care economy oriented around sick care” rather than keeping people healthy. However, he said, the situation is improving as a result of “more innovation and technology and disruption.”

“If we’re not focused on the oldest and poorest and sickest … our eyes are off the ball,” Slavitt replied. “That’s where innovation needs to be. We don’t need another gizmo.”

6.

Spotlight Health happened to coincide with last summer’s lead-up to the Senate’s stalled (and ultimately failed) Better Care Reconciliation Act of 2017. It is hard to keep track of all the health-care-related congressional nail-biters of the past year. This was the bill—devised by a cloister of thirteen Republican male senators—that would have reduced Medicaid spending by $772 billion, leaving 22 million more people uninsured by 2026. Despite the jarring inhumanity of this plan, the debate in Aspen indulged the fantasy of free-market fundamentalists and universal coverage advocates joining forces to create a workable system. We should all look forward to the day when, as predicted in the festival literature, they “find balance between a market-based health system that stresses personal responsibility and choice with a human rights approach that considers affordability and access to care to be the highest priorities.”

I happen to be writing these words, seven months after my trip to Aspen, on the eve of a government shutdown. The limits of rational discourse are clear. I can’t help but scoff at the facade of bipartisan reconciliation draped over the completely contradictory views of society that Slavitt and Chen represent. On the one hand, the rhetoric of self-reliance and individualism. On the other, a conviction that we are responsible for one another.

In On Immunity: An Inoculation (2014), Eula Biss reflects on the belief in the individual body as sacrosanct, especially as harbored by anti-vaxxers. Many parents choose not to vaccinate their infants because of a line of flawed logic: “AIDS education taught us the importance of protecting our bodies from contact with other bodies, and this seems to have bred another kind of insularity, a preoccupation with the integrity of the individual immune system,” she writes. This analogy, while not perfect, relates to the GOP’s concern about insurance markets merging those who are vigorous and self-sufficient with those who are feeble and needy. When a disproportionate share of sick individuals buys into a plan, it is known as an “adverse selection.” There is a Darwinian selfishness—not to mention a delusional optimism—to this idea that illness can be categorically isolated from health.

7.

One recent afternoon, I stepped onto a crowded train at Columbus Circle in New York. It was the week of the “bomb cyclone,” and everyone seemed shell-shocked, trundling along in their heaviest winter coats. I am one of those people who won’t touch a subway pole on the best of days, let alone when half of the riders are coughing. I tried to only breathe inside the space between my face and the gigantic scarf I had wrapped around my upper third. An ad above the crush of fellow passengers caught my eye: a photograph of a young woman’s neck, her face and décolletage cropped just beyond the picture. Her black hair was pulled back, exposing the shelf of her collar bone and straps of her bra, white against brown skin. Her fingers grazed the edge of a thin, faint scar that drew a horizontal line across her throat. Above the scar she wore a blue Band-Aid with the words “I’m covered.” “Cancer care is covered,” the copy reassured, alongside the web address for Oscar, a tech-based health insurance start-up—cofounded by Jared Kushner’s younger brother—that launched in 2014, when Obamacare went into effect. The company is valued at $2 billion, and, according to Forbes, has “more than 250,000 individual products,” which is to say people, enrolled under the Affordable Care Act for 2018.

I live in California now, but I travel back to New York every January for my annual cancer checkup, which entails blood work and an ultrasound of the lymph nodes in my neck. I received the test results the day before I saw the ad. “No news is good news,” my doctor had said. Despite the positive outcome of this year’s pilgrimage to Memorial Sloan Kettering, after the appointment I spent much of the afternoon curled on the couch, inert. I can go for weeks without thinking about the cancer cells lurking inside of me. But these yearly returns to the performance of patienthood unfailingly undo me.

I have the same scar, the same shade of skin, the same shoulder-length black hair as the woman in the subway ad. In the age of targeted marketing, the synchronicity felt uncanny. I got off the train at West Fourth Street to transfer to a downtown C. It was freezing underground, and bustling. I looked up the Oscar website while I waited. “Health care is broken. We want to fix it.” I sneezed. Sounds like something I might have heard on a panel in Aspen.