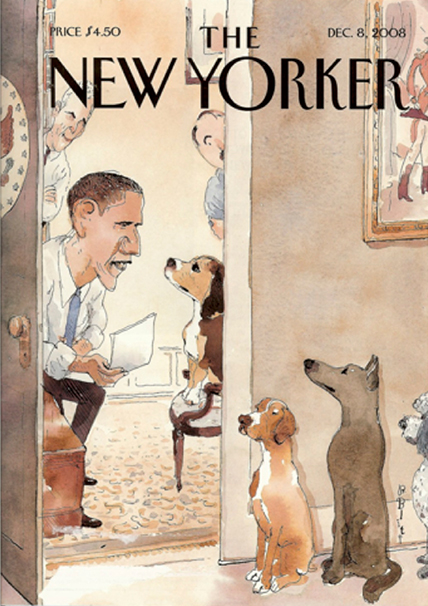

On January 21, 2009, the day after Barack Obama’s inauguration, I had a solo performance scheduled at Dixon Place, a theater on the Lower East Side. For the occasion I decided to make two animals, a dog and a unicorn, out of foam core. The premise of the performance: I’m dogsitting for the Obamas while they attend the inauguration.

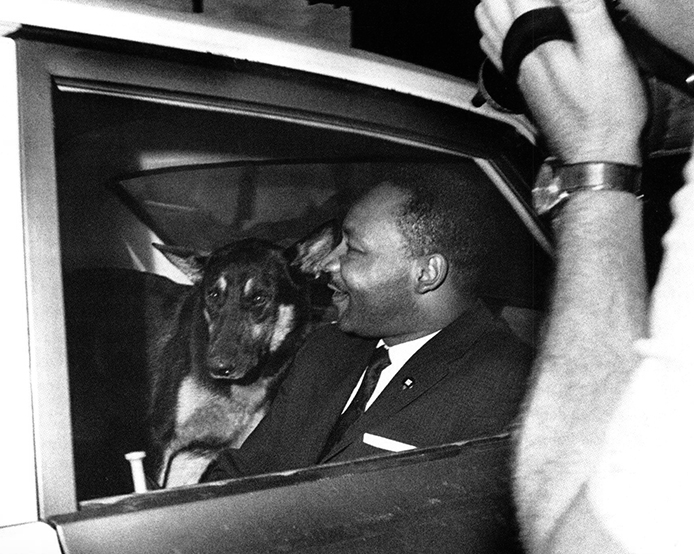

A few months prior, in the victory speech following his election, Obama promised his daughters that he would adopt a dog for the White House. The “puppy moment,” as the press dubbed the incident, spawned a nationwide “puppy watch.” Around that time, the image of a certain kind of dog popped into my head. I felt like it had always been a part of me, an unstable composite of childhood pets, family lore, and political history, an image whose meaning could not be trained to sit still.

I used the foam core to make a cutout of that image: an obedient German shepherd. German shepherds are widely admired for their versatility, intelligence, and ability to do specialized work, especially for armies and the police. They are also specters of the Jim Crow era—a part of American history that seemed, speciously, to be resolved by Obama’s triumph—when they were frequently used to suppress civil-rights protests. The unicorn’s presence was to serve as a symbolic gateway, leading the audience to speculate on the way animals can act as vehicles for the imagination.

The public’s fascination with the presidential dog seemed to be rooted in questions of pedigree. The puppy watch may have temporarily diverted the national obsession with lineage—embodied by so-called birthers questioning Obama’s citizenship, religion, ethnic heritage—but at the same time it symbolically mapped Obama’s “qualifications” onto the vetting of the presidential dog. During Obama’s first post-election press conference, a reporter from the Chicago Sun Times asked about his plans for the first pet. “This is a major issue,” he replied. “I think it’s generated more interest on our website than just about anything. … Our preference would be to get a shelter dog, but, obviously, a lot of shelter dogs are mutts like me.”

I gave away the dog and unicorn after performing with them twice. Later, in 2010, I created a second dog for a performance at Danspace Project at St. Mark’s Church in Manhattan. I used that dog again in 2011 at La MaMa Theater. (By this time, the Obamas had adopted a hypoallergenic Portuguese water dog named Bo.) For three years, I lived with the second dog propped up in my apartment. My performances with the dog began to include routine domestic activities such as dressing, undressing, standing, sitting, fidgeting, lying down, as well as crawling, posing, staring at the dog, and moving it from place to place. At the same time, this budding series of dog dances, which I titled O! Collected Fictions, always returned to Jim Crow imagery and the perceived animality of my own body. The dog became a symbol whose meaning was variable and potentially limitless.

Most accounts of the origins of the German shepherd credit Max von Stephanitz, a nobleman from Dresden, with founding the breed in 1889. Some believe that the German shepherd resulted from the purposeful mixing of two breeds from the north and south of Germany, so as to symbolically integrate the country’s many fractious political and cultural groups (which were formally unified in 1871). Whatever the case, Stephanitz inaugurated the German shepherd breed with his own dog, Horan von Grafrath, who subsequently begat Hektor von Schwaben, who begat Beowulf, Heinz von Starkenberg, and Pilot III. Stephanitz described the shepherd as the “primeval Germanic dog,” linking the breed to myths of the German Volk. “In time immemorial,” Stephanitz wrote, “the warlike proud German held in high esteem his courageous hunting comrade who helped him in his struggle with the rampaging wild-ox, the destructive boar and the greedy beast of prey.” Stephanitz pushed for the breed to be employed by the military and police. “Utility is the true criterion of beauty,” he asserted.

In 1907, the first American police-dog program was launched in New York City with imported German shepherds; cities across the Northeast and Midwest soon followed suit. That same year, Otto Gross vetted an imported shepherd named Mira von Offingen, who was presented in the “open class” category in dog shows in Philadelphia and New Castle, Pennsylvania. These appearances led to the founding of the German Shepherd Dog Club of America. During World War I, for both Europeans and Americans, the shepherd came to be known for its abilities as a messenger, tracker, and guard dog, a reputation that was solidified by the celebrity of Strongheart, one of the earliest canine film stars and the inspiration for the famous Rin Tin Tin. After an American soldier named Lee Duncan rescued him from a bombed-out German kennel in France during the war, Rin Tin Tin appeared in twenty-seven Hollywood films and even received the most votes for Best Actor Academy Award in 1929. After his death, eleven subsequent generations of shepherds carried his name on screen.

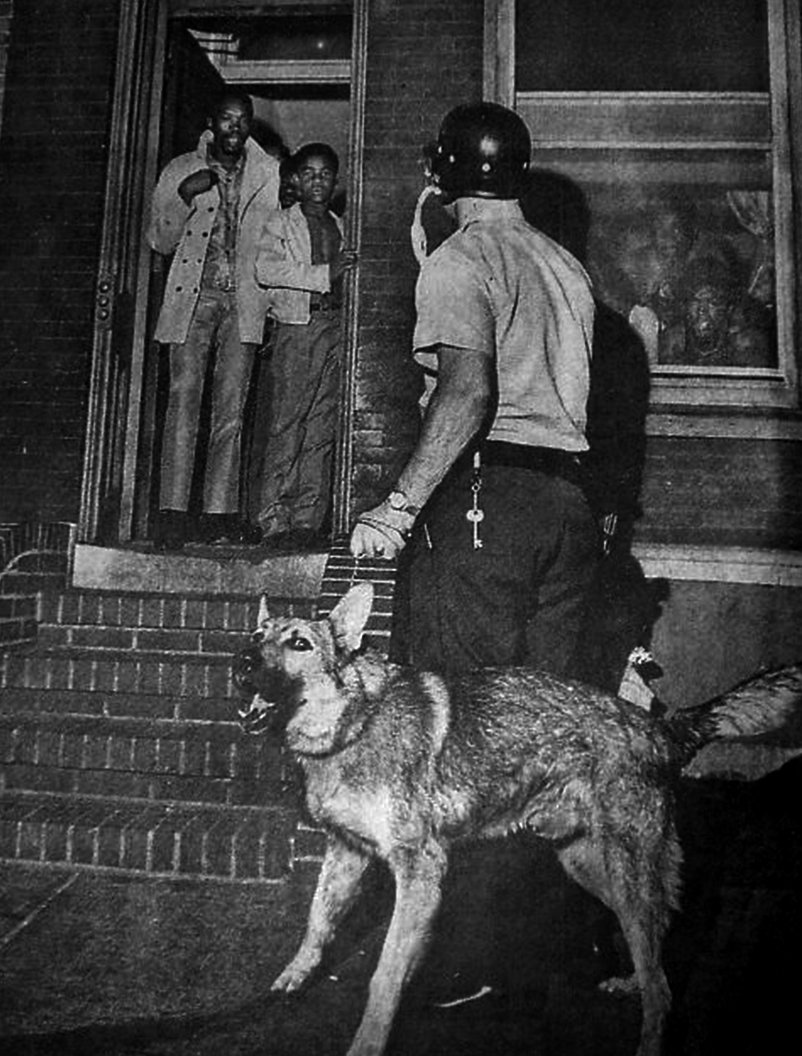

After World War II, when the Dogs for Defense program supplied shepherd sentries to the US armed forces, the German and American lines diverged. The shepherd’s popularity rose rapidly in the US, where breeding methods were guided by aesthetic, typological mixing. (The German line was subject to rigorous inbreeding.) At the same time, the use of German shepherds as police dogs became more common, and spread to the South, where the dogs were deployed to enforce the segregation laws and terrorize protesters. An Associated Press photographer in Birmingham, Alabama, captured a policeman’s German shepherd sinking its teeth into a young man in 1963, and the image quickly became emblematic of the violence roiling the region. This image always infuriates me. When I see the dog tearing into the man, I immediately think of my father as a young black kid dodging BBs fired at him by white neighbors on his way to school in Georgia.

At age eight, I became obsessed with The Journey of Natty Gann (1985), an epic coming-of-age film, set during the Depression, about a runaway girl and her dog—who is actually a wolf. The girl, Natty Gann, saves the wolf after he kills a Doberman pinscher in a dog-fighting ring—a clear tribute to American military prowess. In return for her kindness, the wolf guides Natty through the American wilderness, protecting her as they hop trains and search for her father, who has abandoned his child to take a job as a logger in Washington.

Due to my ancestors’ migration among plantations in the late nineteenth century, and the consequent absence of any documentation of their lives, my father’s lineage was conveyed to me orally, as lore riddled with gaps. (One of the few details I’ve collected is that my great grandmother was a Cherokee chief called Big Red.) As a child I reenacted the journeys of Natty Gann while in my backyard in Dorchester, a neighborhood of Boston with a racially mixed population of poor and middle-class families. My costar was my dog, Sandy, a mutt of German shepherd and Collie descent. I imagined myself both as Natty and as my father, Oree, who grew up as a sharecropper on a farm in Waycross, Georgia in the 1940s and 1950s.

Email interview with Oree Rawls, December 21, 2013.

Will How did you end up getting Sandy?

Oree I got him as a puppy from a police officer named Loletha Graham.

Will Was he well trained? Was he well loved?

Oree I would not say Sandy was well trained. He was struck by cars twice and was nearly killed once. You could leave him on the porch and he would stay there unless another dog came by. I don’t remember but one dog that he got along with, and that was J. C. He was loved.

Will What were Sandy’s best qualities? What were his worst qualities?

Oree Best quality was good with kids. Worst quality was he didn’t like other dogs—period.

Will Did you have dogs growing up on the farm?

Oree We always had dogs growing up in the country. All the dogs we had were hunting dogs and they never slept in the house. Dogs slept outside, but they slept close to the chimney in the winter time to stay warm. I was a little surprised when I got up here and found that the animals slept inside.

Will Would you consider yourself a dog person?

Oree I consider myself a dog person. I have always loved dogs and I still do.

Will Did you ever have any run-ins with dogs growing up?

Oree My only run-in was with Z. A.’s parents’ dog, who was named Hitler. Every time anybody passed their house he would try to get at them. Most of the dogs that I grew up with was hound dogs or just plain mutts that we used for hunting. I can’t remember what breed of dog Hitler was—just that he was a mean, nasty dog.

Will What is your last memory of Sandy?

Oree Sandy developed tumors that could not be treated. My last memory of the dog is taking him to be put to sleep.

My mother, Florence, is a blond of Welsh descent. A nomad during her childhood, she was born in Buffalo, New York and moved every two years until she was fourteen, mostly among upper-middle-class neighborhoods in Ohio and Connecticut. When I was a kid, before I went to sleep, she used to sing “Old Blue,” a beautiful Southern blues song about a farmer and his dog. “Old Blue” is not the happiest lullaby, but the sadness in the song makes it easy to recall. The song developed in minstrel shows along the Mississippi River in the late nineteenth century then drifted north along the Mississippi Valley in the next century and branched into several versions.

I imagine that my mother learned “Old Blue” while trying to connect to a sense of place possessed by my father, and wanted to pass the song—and the blues—on to me. But she probably already knew “Old Blue” when my parents met, since Joan Baez recorded a version in 1961. When my mother and father met, in 1971, they both worked at a Boston concert hall called the Aquarius Theater; he was her boss. Ike and Tina Turner performed there, as did Nina Simone. According to my dad, Simone arrived at her own concert two hours late, then cursed out the white people in the audience before she performed. Afterward, Simone blamed the whole mess on my father.

My parents married in 1973: a north-south wedding held in New Hampshire. Their first dog was a coonhound named J. C., which my dad brought to Boston from Georgia. My parents got Sandy in 1984. He had a blond coat and a white chest and looked more like a lion than a wolf, more feline than canine.

Sandy walked me to the subway in the morning and waited to meet me when I returned in the afternoon. He usually spent the rest of the day trailing the trash men, who fed him scraps. In the evening my dad fed Sandy dry dog food drenched in bacon grease with some warm water and a bone if he was lucky. I imagined this is what our family had fed the dogs on the farm. I tasted it once.

Earlier this year my mother told me that I come from a long line of dog breeders on her father’s side of the family: They raised setters, spaniels, Labradors, and golden retrievers. These dogs were often trained for use in the fox hunts that took place on my the plantations her grandparents owned in Ohio and Georgia. “Old Blue,” it turns out, was sung by my mother’s family throughout her youth.

“Old Blue”

(Florence Rawls version)

Well I had an old dog and his name was Blue,

Betcha five dollars he’s a good dog too

Singin’ “Come on Blue”

“You’re a good one too”

Now Old Blue died and he died so hard,

He shook the ground in my backyard

I dug his grave with a silver spade,

And lowered him down with a golden chain

Every chain link I called his name

Singing, “Come on Blue”

“You’re a good one too”

Now when I get to heaven, first thing I’ll do

Pull out my horn and call Old Blue

I’ll say, “Here Old Blue”

“Good dog you”

I made the final dog piece, Frontispieces, in February 2012, as a commission for Danspace Project. Frontispieces was to be part of a festival that asked: What is black dance? I created seven more dogs, each with the same contour but with the surface painted differently. Six of the dogs were painted with abstract designs; the other two were painted realistically. These two were almost, but not quite, identical—doppelgängers, each nearly passing as the other, yet marked by the distinctions that result from breeding. I painted the reverse side of each dog gray, so that together they resembled a pack of wolves. I wanted to invoke the return of the dogs to nature, to a time before they were useful to mankind.

As I made my dog dances, I thought about Jorge Luis Borges, who is simultaneously narrator and protagonist in many of his circuitous historical tales. In particular, I dwelled on “The Zahir,” the story in which Borges—as a character—recounts his fixation with a magical coin, whose meaning is constantly expanding. According to the story, the word zahir (which in Arabic means “visible, evident”) has referred to countless things throughout history: a tiger in Gujarat in the eighteenth century, an astrolabe in Persia that was thrown into the sea, a vein in the marble of a pillar in the Córdoba synagogue, the bottom of a well in the Jewish quarter of Madrid. The significance of zahir is potentially limitless. “I reflected that there is nothing less material than money,” Borges writes,

since any coin (a twenty centavo piece, for instance) is, in truth, a panoply of all possible futures. Money is abstract, I said over and over, money is future time. It can be an evening just outside the city, or a Brahms melody, or maps, or chess, or coffee, or the words of Epictetus, which teach the contempt of gold; it is a Proteus more changeable than the Proteus of the Isle of Pharos. It is unforeseeable time, Bergsonian time, not the hard, solid time of Islam or the Portico.

Anyone who comes into contact with the physical incarnation of the Zahir slowly forgets all else, succumbing to a desire to know only the coin and its many facets. “Today is the thirteenth of November,” Borges writes, recounting the coin’s effects on him. “Last June 7, at dawn, the Zahir came into my hands; I am not the man I was then, but I am still able to recall, and perhaps recount, what happened. I am still, albeit only partially, Borges.” The protagonist ultimately gives away the Zahir in an attempt to salvage his own sanity.

After the last Frontispieces performance, I gave away all but one of my German shepherd cutouts as souvenirs to audience members. Later that night, I passed someone in the East Village who was carrying one of the dogs, which she had found leaning against a lamppost in the snow.

One year later, I went to an artist’s colony, which was lush and sprawling but bore the marks of landscaping; the setting was both natural and domesticated. I brought along the last cutout dog, which I planned to photograph during my stay as a memorializing ritual. I wanted to put its foam-core body to rest and with it a century of dog years. Unsurprisingly, I had trouble capturing the nexus of movement, nation, and family in any single image. I photographed the dog in numerous poses during those weeks, turning its body over and over, coaxing it to change its shape once again.