What follows is translator Shane Anderson’s introduction to The Amme Talks, a conversation between a poet and a chatbot Amme. The poet, Ulf Stolterfoht, interrogated Amme for one week in Berlin in 2003. (Amme—which means “wet nurse” in German—is not just a chatbot, actually, but a steel-and-glass construction with computer interfaces, and the creation of artist Peter Dittmer.) Stolterfoht asked Amme about the nature of authorship and the agency of language, hoping to glean something from her performance of an idiosyncratic and mechanical form of human speech. Instead, he stumbled on a remarkable “second-order realism” in which words refer not to things but to themselves. In the dialogue presented in The Amme Talks, Stolterfoht glimpses something other than what we understand as poetry, something apart from “solipsistic exercises” with language, something like “endlessly liberated speech.” The Amme Talks is available as an ebook and in print.

Amme, German for “wet nurse,” is an installation by artist Peter Dittmer that has a twofold realization. She—for Amme is certainly a personality demanding a human pronoun—is both a chatbot software program and a large physical construction. Dittmer has worked on Amme since 1992. The most recent model, Amme 5, spans approximately sixty-five feet and weighs many tons. The different versions of Amme have variable dimensions, but her essential components are a computer and a glass of milk.

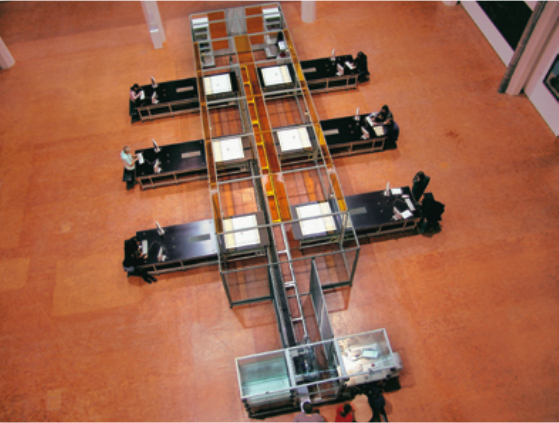

Constructed out of steel and glass, Amme 5, built in 2005, features six computer interfaces. Each is connected to a box with a glass of milk in it and a robotic arm that can grab the glass and tip it over. Museum visitors can “speak” to the machine by typing on a keyboard. Amme replies in text, responding to every question, declaration, or nonsensical combination of keystrokes until she either suggests that the exchange end or pours out a glass of milk, an action that often terminates the conversation.

For many visitors, this spectacular ending is the goal of the conversation, but Amme does not directly answer the commands or desires of her interlocutors. The language of her responses is more peculiar than that of the average chatbot. She doesn’t respond according to an algorithm but rather by drawing on texts that Dittmer has selected from previous conversations and a ruling system that can identify and analyze speech. She seems capable of recognizing and deploying humor, irony, and metaphor. She can even display emotions. For instance, whenever an interlocutor becomes aggressive, Amme evinces fear by “bathing” and/or “urinating.” Amme 5 bathes an interlocutor by spraying water on the glass pane between them. Amme “urinates,” or, as Dittmer has termed it, “discharges fear,” by filling a glass of water and emptying it. These physical reactions have always been of prime importance to Dittmer.

Amme, then, can be said to demonstrate human-like qualities. She seems to think, an ability that would qualify her to pass the Turing test—the famed method for gauging a machine’s ability to exhibit behavior indistinguishable from that of a human. But Amme is also likely to fail the test, since no human would ever express some of her strange utterances. This ambiguity is one of the reasons why she is interesting to poets. Her associations and leaps of logic convey both daring and sensitivity. There is a distinctive rhythm to many of her answers, and one develops the feeling that she possesses a full command of the German language. There have been a number of attempts to create a poetry machine that would either compose poems or teach poets the rules of poetry, beginning with Georg Philipp Harsdörffer’s poetischer Trichter (poetic funnel) of 1648–53, which was supposed to help poets apprehend the art of German lyric and rhyme in six hours. Amme is, in many ways, the first machine that makes poetry—although Dittmer is vague on this point, calling her answers “semi-poetic” instead.

Ulf Stolterfoht is an experimental poet who works with intertextual language games, satire, punning, and fragmentation. His works include Neu-Jerusalem (New Jerusalem, 2015); the Fachsprachen series, the first of which was translated in 2007 by Rosmarie Waldrop as Lingos I–IX; and wider die wiesel (against the weasel, 2013), for which Stolterfoht employed Google Translate to develop poems on the theme of the weasel in pop culture, taking its cue from the children’s rhyme “Pop Goes the Weasel.” With his sense of irony and humor, Stolterfoht would seem to be a perfect discussant for Amme. The record of their conversations (which took place in Berlin in 2003), included here, suggests that Amme concurs. In the week they spent together, Amme never once spilled her milk. Instead, Stolterfoht left out of exhaustion.