In Douglas Sirk’s racially charged 1959 melodrama Imitation of Life, Susan Kohner plays a moody wannabe white girl named Sarah Jane. Eager to distance herself from the fact that she is half black, Sarah Jane repeatedly tries to pass for white; in a final rebellious attempt to forever forsake her dark-skinned mother, Annie, played by Juanita Moore, Sarah Jane wails, “I’m white, white, WHITE!” In true Sirkian style, Sarah Jane crumbles to the floor in front of a motel mirror in which her black mother is mirrored.

I have a fantasy in which Dionne Warwick’s “Don’t Make Me Over” plays in the background during this scene.

To revise a scene is to impose one’s readerly desire, and why be mealy-mouthed about it? The cinematic unconscious knows no such thing as “overkill.” Watching a film is a way of connecting dots in the dark. Whichever dots are left I call my thoughts: the ripe, awkward, unpluckable chunks. Here are some:

- Juanita Moore died on January 1, 2014.

- I currently live in the historically black neighborhood of Bed-Stuy, where I initially moved to either hide or fit in. Lately, however, I find myself increasingly paranoid that my black neighbors will mistake me for white.

- To inhabit the self-consciousness of certain images, images that interpolate and then act against us, is a Sisyphean chore. You prop up an image believing (stupidly) that it’s the image’s job to bowl you over and leave you floored. Textual devotion is like that, which is to say that reading is a culturally specific and irrational form of invisible worship and/or work. What we choose to read, and read into, says a lot about us.

- Sure enough, after I tell my neighbor my last name, he raises his hand to his forehead in a gesture of comic relief, or possibly in shame. “Oh my Lord, but why did I think you was white?”

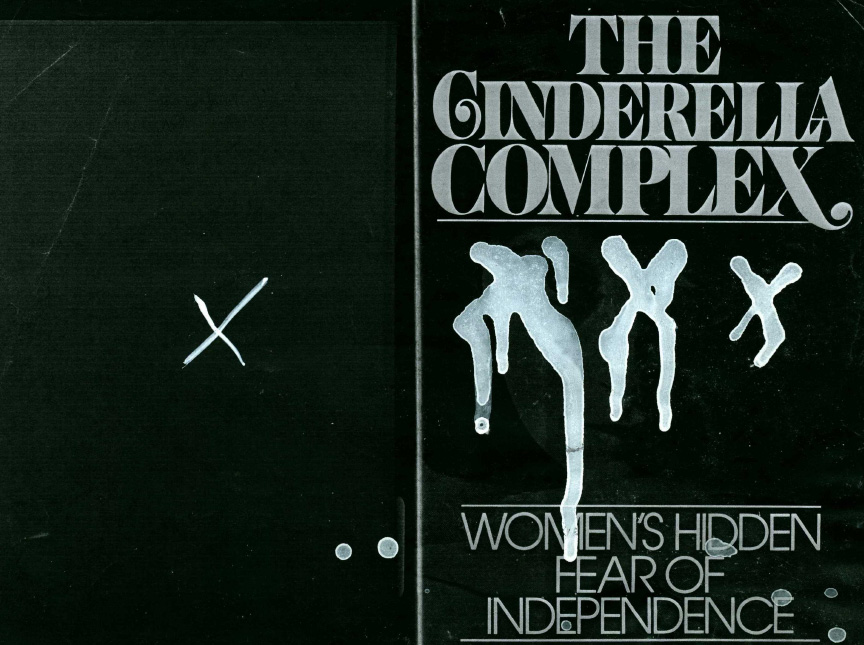

My reading sneaks into broken homes. I write these poems in somebody else’s sink. First I settle in and imagine I am the foaming dishpans in Chantal Akerman’s film Jeanne Dielman 23, Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975). I am a cheap piece of porcelain sudsing in a basin of filth, where I submit to boredom’s crepuscular rhythms and, in so doing, slip into the crack that divides being and doing. These are my domestic trances, where I come to do the work that is reading. Depending on what I am reading, I may find myself roused to rage, stupor, rapture. But submitting to these affects does not necessarily enable me to sit still, write, and type. Nevertheless, while deferring the anxiety prompted in me by dissertation research—a study on confessional poetics—I temporarily abandoned Anne Sexton’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Live or Die (1966) to immerse myself in a far less noble object: Colette Dowling’s The Cinderella Complex: Women’s Hidden Fear of Independence (1981).

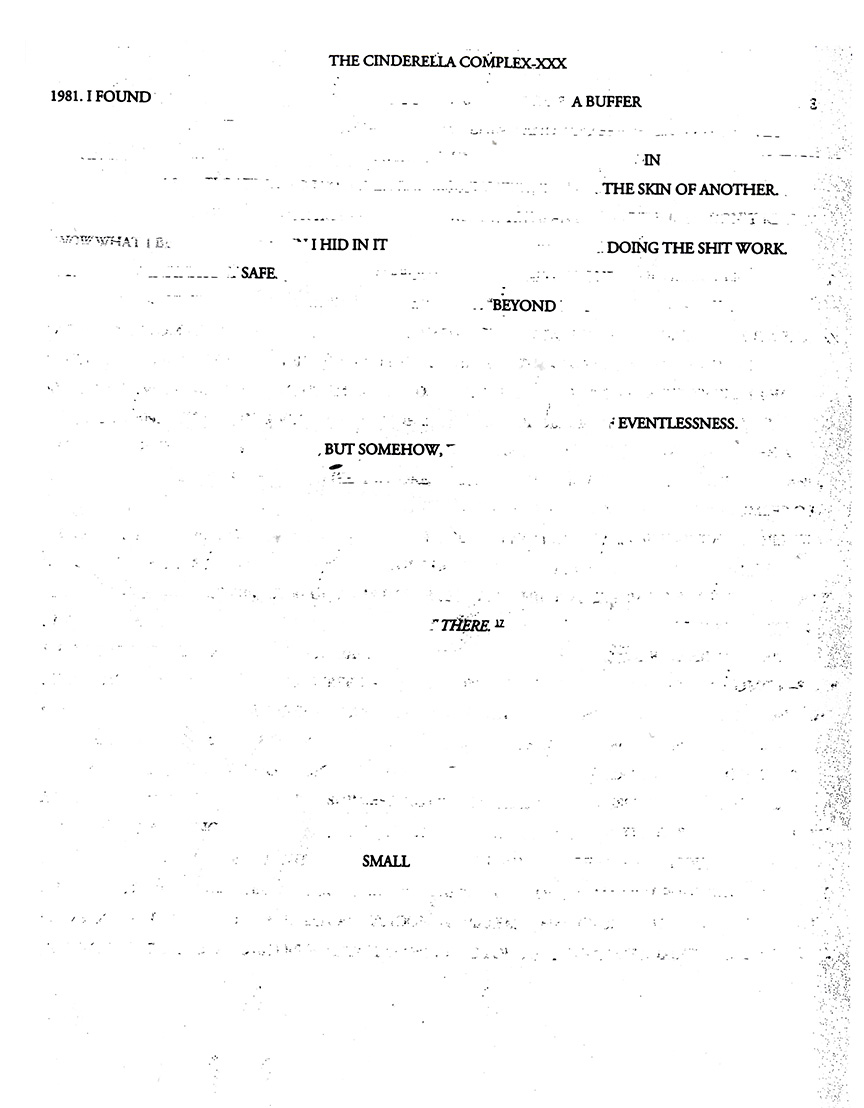

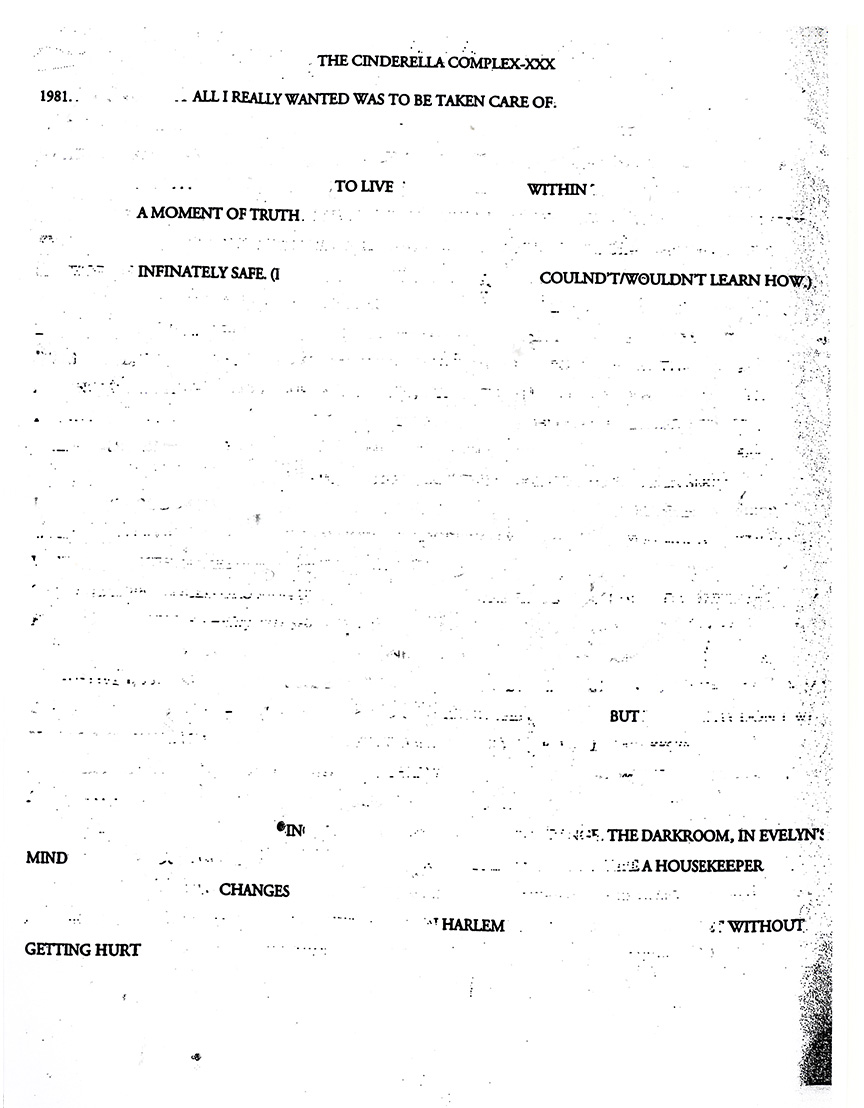

Dowling, a housewife turned self-help guru, describes the lure of dirty work as part and parcel of domestic trances: “Inwardly, I wanted to be doing the shit work. Shit work is infinitely safe.” Akerman’s protagonist, Jeanne Dielman, would never make such bold proclamations. Too profane. And yet I can get behind exhibitionist confessions such as Dowling’s because they speak to the bottom in me, who longs to spend some time in the holding environment that is the kitchen sink. As a dishpan in the sink, or a reader—perhaps now in bed—I’m infinitely safe within my routines. In Jeanne Dielman, shit work induces trances coextensive with the zazen world of objects, a world imbued with the luster of process. Surrounded by objects, the mind wanders. Jeanne Dielman, a less provincial Cinderella, bends, lifts, boils, folds. Written on Dielman’s face are signs of a perverse, private ecstasy. Wash, dry, hang, and shine. Safe. Each object maintains its proper place and time; each object helps pass the time. Housework isn’t unlike reading. Beat, trickle, leak, and drip: Objects supply a music for Jeanne Dielman’s elegantly choreographed kitchen-think:

scrub stab grind plug/unplug pour percolate

Between these verbs are poems. Between acts I insert myself, I occupy a magic space known as the periphery. The periphery is a necessary place. I say necessary because there can be no verbal life, no consciousness of the dishpans, without the periphery. Here dwells the concrete peace of shit work. Between acts I am infinitely safe. I sometimes think that Jeanne Dielman is Cinderella sans Cinderella. What need has she for a prince? Undisturbed by prospects of narrative, monogamy, or marriage, Jeanne Dielman lives. Leave me to my (mother’s) cinders or leave me alone. In The Book of Disquiet, Fernando Pessoa writes, “Art is the Cinderella who stayed at home because that’s how it had to be.” A private world manifests itself between foaming dishpans and leftover flour. Jeanne Dielman moves beyond the mythic, suggesting that there is, in fact, Art—an art to our drudgery, an art to our reading, an art to our shit work.

A poetics of the dishpan might suggest that foaming and letting-foam can be a critical way of engaging with the world. Sometimes, to do the necessary work of being, one need only sit overnight. Do nothing but suds. To suds is to postpone the act of cleaning up, also known as tidying up. Sudsing is the respite one takes from scrubbing. Synonyms for sudsing include: sitting, soaking. Sudsing and other forms of private percolation are typically seen as antisocial activities.

The Cinderella Complex by Dowling has spoken to me in registers both familiar and frightening. It has caused me to bark, furrow, wince, and frown. Like Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman or Betty Freidan’s The Feminine Mystique (1963), The Cinderella Complex aspires to speak about a problem with no name. Projects and objects that aspire to speak out of turn about the unnamable move me. But projects and objects that immerse themselves in the difficult and ambitious task of naming—these occupy another category of wonder and bliss altogether. To speak in a text rather than speak “on” a text is to be stupid. Dumb as a dishpan. My poems are written in the prosody of a reader speaking in and speaking back to the bliss I experienced after having encountered Dowling’s dumb and dumped object. A dated and dismissed object. How often have I allowed myself to be dismissed? More than once I have chosen to remain quiet at pivotal junctures and decisive moments. Think of it like this: In a musical score, that which is unsaid is, you assume, understood: tacit. I take comfort in certain silences and secret vows. In these poems I have tried to bury myself, scattering the parts among private pronouns. To be a poet is to accrue things, speak in fragments, sneak into sinks.

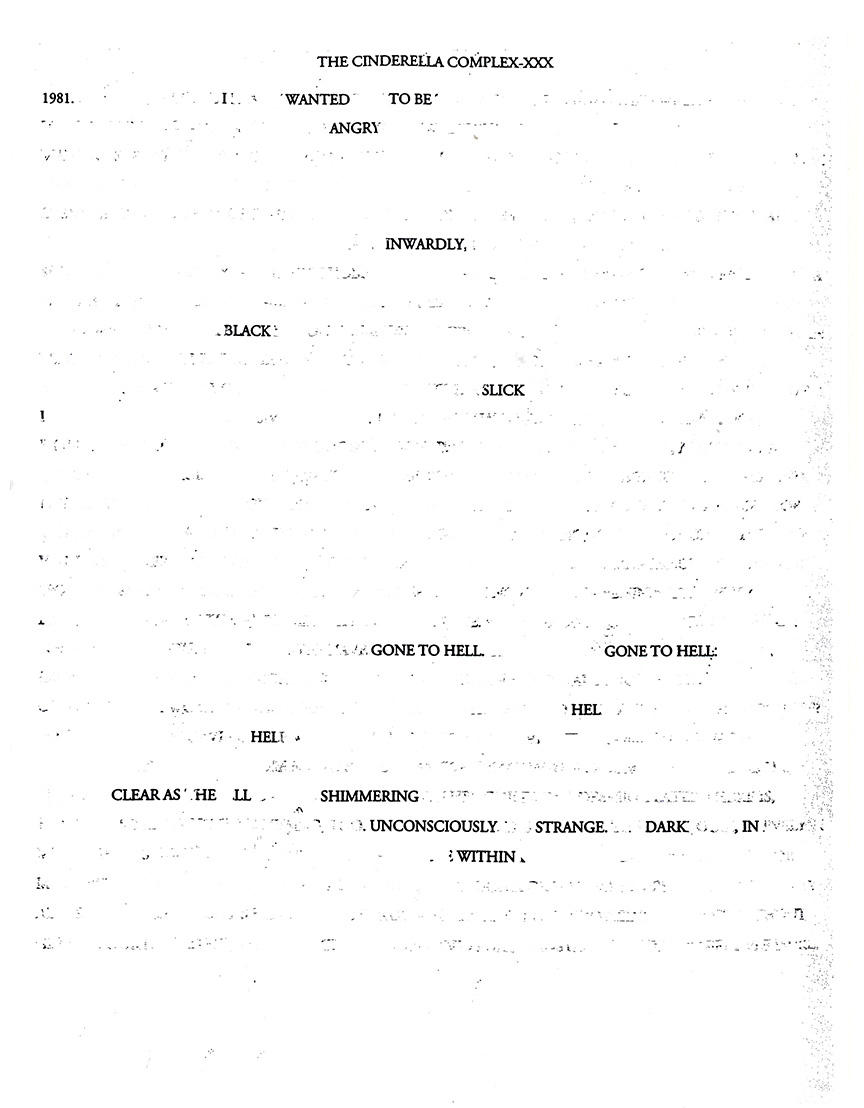

I have contributed no original words. The gestures that shape my erasures are original insofar as they reveal, by way of transcription, Xerox, and whiteout, the manifold and ambivalent readerly responses begotten by The Cinderella Complex—a haven, I discovered, of domestic improprieties and middle-class anxiety. From a den of bad manners, a filthy kitchen, emerges THE CINDERELLA COMPLEX-XXX.

Dowling defines “The Cinderella Complex” as

a network of largely repressed attitudes and fears that keeps women in a kind of half-light, retreating from the full use of their minds and creativity. Like Cinderella, women today are still waiting for something external to transform their lives.

What were women in 1981 waiting for, I wonder, and are we still waiting? I’m waiting for a comrade and a coworker. I wonder if I will ever find a collaborator who can both help me get off and help me get things done. Perhaps in images, then, I settle for a cohort of objects to help me ride out the wait. When I think of Jeanne Dielman in 1975 and the scenes in which she is waiting, I don’t really see her waiting for anything beyond the beauty of boiled potatoes. I admire Jeanne Dielman mainly for this reason: because she is not, to use Colette Dowling’s words, “a putterer.” A putterer is a person who putters about, occupying herself in an aimless or ineffective manner and wasting time; an idler. Other words for putterer include

dawdler laggard lagger trailer poke drone bumbler

A putterer is someone who takes more time than necessary, who lags behind. I envy Dielman. She is an expert, as efficient with words and gestures as she is with tinfoil. I wish I were as resourceful with leftover scraps of Reynolds Wrap, but I am not. I putter on. If you feel yourself a hausfrau, or frustrated poet, puttering may involve reading books you know you will not be any better for having read. One takes a toy mallet to make tender a piece of toughness.

The Cinderella Complex advertised itself from the outset as a book that would disappoint me, yet I went forth in my search for Cinderella, expecting to idle in a rhetorically defunct space, a periphery. I quickly realized I could not sympathize with this charmed object, for Colette Dowling suffers from a much more serious affliction than a so-called Cinderella Complex. I will narrate her symptoms, as she herself reports them:

Something was sabotaging my confidence, some inner confusion about who I was, and what I wanted to do with my life, and what girls were about in general. But all of this went unrecognized.

She recalls the work of white girlhood:

Long praised by teachers for being diligent and dutiful in school, we [women] who rely on dutifulness to get by in the professional world soon find ourselves being treated as if we were not quite grown up. Virtuous, perhaps. Nice, perhaps (as in “Isn’t Mary nice to take care of all those back orders for us?”). But childlike. Not to be taken seriously. And, like the good slaves on the old plantations, easily exploitable.

Oof. In her analysis of the melancholic condition of race in America, scholar Anne Anlin Cheng, borrowing from Ralph Ellison’s The Invisible Man, observes, “we gag on what we refuse to see.” As Dowling progresses in her thesis, the blunders get even uglier, and the unresolved nature of the author’s racial ambivalences become increasingly pronounced.

Sheer exhaustive busyness can smoke screen a lot of things. We all know about women—some of us are those women—who could afford to hire household help but don’t. Why don’t we? Precisely because having help would set us dangerously free.

Help: a heavy word; but for whom do such possibilities exist? Here I turn away and mark my cynical departure from The Cinderella Complex in order to interrogate the problematic “we” Dowling has employed, as have other white feminists.

The Cinderella Complex was published in the same year as the seminal anthology This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color, edited by Cherríe Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa. In the book’s preface, Moraga writes that one of the motivations for an anthology written exclusively by feminists of color is to confront “the pain of … dealing with white women.” Moraga, among others, attributes her pain to the fact that white feminists were mostly unwilling to struggle with the difficulty of admitting women of color, along with their socioeconomic baggage, into the discourse of women’s liberation. Books like This Bridge Called My Back carried with them an affective charge: mutual estrangement, hostility, disappointment, and rage. bell hooks’s Ain’t I a Woman?, also published in 1981, accounted for the lack of attention to black women in most scholarship. “Throughout American history, the racial imperialism of whites has supported the custom of scholars using the term ‘women’ even if they are referring solely to the experience of white women,” hooks writes. “Yet, such a custom, whether practiced consciously or unconsciously, perpetuates racism in that it denies the existence of non-white women in America.” Like the editors of This Bridge, hooks holds scholars responsible for deploying the word woman to reckless and racist effect.

The mission of these texts was to disrupt the taken-for-granted “we” of American feminism: white, liberal, middle-class, and college educated. The Cinderella Complex was written from this privileged point of view. Dowling was correct in asserting that women were guilty of waiting for something, namely Prince Charming, but Cinderella waits not for just someone to save her, but also, or rather, for someone to pick up after her. In other words, The Cinderella Complex is a narrative about passing the mop and the bucket to darker, less fortunate sisters: “the help,” as Dowling euphemistically calls them. But what is criticism if not historical housekeeping? It is another contemporary chore, but would I have a job without it?

In her essay “Happy Objects,” scholar Sara Ahmed writes: “We are moved by things. In being moved by things, we make things.” Though I felt moved by the aspirations of The Cinderella Complex, ultimately, I was deeply disturbed by its racism, as well as its rhetorical entitlement, a testament to its status as an unhappy object—one that feminists would rather forget. I wanted my new object to bear the mark of my having been moved, but I also wanted it to bear the mark of my fatigue, as well as my disappointment. I set about xeroxing the book’s cover. As we know, a photocopy machine never just copies. As a tool of transcription, such an object also contributes to the rewriting and subsequent redeployment of any text. The Xerox machine first recorded my encounter with The Cinderella Complex by failing to reproduce the white woman on the cover. I needed to make real to readers that the production of this book is foregrounded by conditions of blackness, as in that aforementioned moment in Imitation of Life when Sarah Jane cries out to the darkness, “I’m white, White, WHITE!” Sarah Jane’s hysterical utterance is understood as that much more pitiable when it is made in front of her mother, Annie, because it is she whom Sarah Jane believes to be the cause of her wretched condition.

But notice how the white woman in my Xerox disappears. That’s what blackness does: renders the subject of white privilege no longer central—negligible. I added the –XXX in order to mark it as my project, the product of my shit work, my labor. The addendum marks my presence as a reader, a reader with a critical intention, a reader with a bit of a grudge. –XXX also marks the number of repetitions I've made via copying and recopying. As with Pola X, Leos Carax’s film adaptation of Melville’s Pierre, a blunder of a novel, it is not clear what version has ultimately arrived in the viewer’s hands. At a Q&A after a recent screening of Akerman’s La Captive, an adaptation of Proust’s “La Prisonniere,” I made the mistake of prefacing a question to the filmmaker by making reference to Pola X. Akerman responded, “Ugh! Please, that was the worst film Carax ever made!” Was she saying, that even after ten tries—since the “X” of the title indicates that the tenth draft of the script was used in shooting—the film should never have been made? –XXX serves to place the poems contained within these pages within the literature of “bad adaptations.”

As historically the burden of explication has belonged to women of color, I have, in these poems, these reckonings, acquiesced to Cinderella’s somnambulance—a kind of “stuplimity,” to use scholar Sianne Ngai's coinage. I imported myself as the brown labor, a Juanita Brown, or “the help,” so to speak. I used Wite-Out to tidy up The Cinderella Complex and reveal its processes of obfuscation. Wite-Out enabled me to demonstrate, without words, that whiteness does have a texture, a presence on the page, especially when rendered by the colored writer’s labors. (Call me simple, but it’s just a bit hard for me not to see the word race in erase. Or for that matter, the con in conceptual.) The more whiteness I added, the more pronounced issues of race became. The ironic results of my erasures always seemed in excess of themselves, and at times, obscene, hence, the –XXX. I suspect in an attempt to live with this text, rather than to live without it, or in its shadow, I am covertly challenging certain conceptual poetics employing similar methods, but do so to no ethically nor ethnographically interesting ends.

To those poets I say, “Shit is shit.”

Happily, there are other traditions that embrace shit work: namely, feminist writings by women of color. It is within this tradition that I situate my poems. In her 1977 essay, “Poetry Is Not a Luxury,” Audre Lorde writes, “I speak here of poetry as a revelatory distillation of experience.” A poetics of foaming dishpans can cut through the grime of experience. So before you read my poems and dismiss my work as “uncreative” or “unoriginal,” I ask that you defer to the terms provided: shit work and menial labor. Even though I believe, alongside philosopher Avital Ronell, that “work makes people stupid,” as both a poet and a scholar of color, having submitted myself to the working conditions of stupidity, I foresee the potential for new, more felicitous forms of textual engagement beyond the kinds explicated here.

There is more poetry, and more shit work, to be done.

Postscript: Conceptual Problems

Reading takes time. My job as a reader is to collate instances of reading as they overlap in care, time, preoccupation, and even slowness, stupidity. Like my objects, I am resistant to narratives that make time move faster than time moves. I am resistant to histories that move more smoothly than history moves. If in our thinking there are accidents, then there must also be skid marks, an ingress for the accidents of thought. The references included in this essay, spanning roughly fifty-five years, are by no means comprehensive, but embedded within them is an argument about the time it takes to recognize the place and potential of a disinherited thing. The Cinderella Complex is a provocative object whose status progresses alongside the racialized time of reading for one American woman. In the year I have spent working with my editor, a white woman, on this piece, I have encountered some unanticipated but important problems. Throughout our correspondence, I have at times had to dance a fine line between crippling rage and syphilitic self-censorship. Every writer knows the business of rejection and redaction, or editing and publishing, isn’t personal, until it is. I could describe this delicate business with words like transference and countertransference, but I won’t. Instead, I will narrate lastly an anecdote which performs some of the “personal” problems I have encountered in the making of this piece, problems which I will not discreetly file away under “conflicts of interest.” In an earlier draft of this piece, I ended with a manifesto of sorts: “So before you read my poems and dismiss my work as ‘uncreative’ or ‘unoriginal,’ I ask that you defer instead to the terms provided: shit work and menial labor.” My editor suggests I cut this part and “end on a different note.” I postpone my editor’s suggestion and wonder what it is like to be a white girl, like my editor, who labors like and unlike myself under difficult working conditions. For a long time, neither of us addresses these conditions. We’re too busy, working. To her, during the editing process, I admit I am afflicted with this condition of waiting, like a white woman, for something. Sometimes, I am waiting for her feedback, but what I need is bigger than that. Should I call today this thing for which I am waiting Justice, or keep seeking, for the sake of my editor, les mots justes?

Essentially, I am at an emotional impasse, ambivalent about future prospects, and in desperate need of a forgiving, likeminded friend. An attentive, sympathetic reader: someone who gets it. By happenstance, I’m endowed with not only a second reader, but a reader who, coincidentally, has also written for this publication. This second reader becomes the thorny place where I test my paranoia as well as my editor’s theories about readership, laziness, and racism’s literary slickness: Me: “What do you think of Hilton Als’s White Girls?” Second reader: “Hilton Als is lazy.” L-A-Z-Y. This observation is among the duller of the Master’s Tools. I know where this “critique” is going, but still, I keep listening. “Als took too long. Fourteen years to put out a book where 25% of the material has already been previously published. It’s not like he suffers from writer’s block.” I did not attempt to contradict this information. After all, who was I, the poet, to talk to the novelist about prose? He continued, “Hilton’s problem is that he’s stuck in the past. Too much lingering.” More valuable information: Hilton Als would be a better writer if he could just “get over it.” My reader, a person of privilege with wounds that reach deeper than this postscript, is saying, Forget what you are: you’d be more widely read, more respected if you could just forget it. Even though I don’t believe him, I get it, and it is in these moments, reading my reader, where I feel bound to him by mutual rejection and a desire for risk: the risk of recognition. I wonder when I will forgive my reader’s bungled truths about work and fiction, the fictions white authors and critics espouse as they boast to know something about “difference,” or black myths as they still circulate: lazy, slow, stuck. In one form or another, every reader, who is also an editor, who is also an author, has been guilty at least once of asking of another to quit being so resistant. Let go. Give up. Move the fuck on. My mother had cervical cancer. I didn’t think about it until I did. That’s partly why this piece has taken me so long to publish. As I am typing this, I take breaks every few hours or so to walk her to the toilet. I am her only daughter. I must help her drain the bag of piss she’s carrying because in surgery her bladder got nicked. Spics. These are the thoughts. Not the time they take. The thoughts I shelve because I’m running late. In no other way will the shit work get done, for my editor, a white woman, or the second reader, an idiot. Can I afford to postpone the unsightliness of certain myths? I have been both a good lay and a lazy spic triangulated by truths that are unkind as they are importunate.