"Ten Chairs" at Ikon, 2010. Photo: Stuart Whipps. Judd Furniture™. © Judd Foundation.

This essay was commissioned as a response to Media Replication Services, an event organized by Triple Canopy in April 2014 as part of Pointing Machines, the magazine’s contribution to the 2014 Whitney Biennial.

1.

On the corner of Madison Avenue and East 60th Street in Manhattan’s erstwhile gallery district stands an imposing building with neoclassical detailing. Unmarked save for a cantilevered rectangle inscribed with sans serif type, the tower’s glass entrance opens onto an airy interior flooded with natural light. Populating the sandstone floors are a series of asymmetrical benches and tables hewn from thick strips of raw pine or slate. Among them stands an anodized aluminum and Plexiglas vitrine, which confers an aura of preciousness onto its contents: rows of scarves and sunglasses. A few backlit cutaways house inconspicuous racks, which suspend swaths of beige and charcoal fabric. All this gives the impression of seriality, of succession—of one thing after another. Upstairs, a low concrete slab serves as a pedestal for crumpled piles of silk in cream and black. In the background, a pine bench and an aluminum chair invite shoppers to stop and contemplate their surroundings: the Calvin Klein flagship store, fully outfitted with furniture by minimalist icon Donald Judd.

This is how the shop appeared in Interior Design and Vogue when it opened in October 1995, one year after Judd’s death at age sixty-five. Klein had made his name by glamorizing boxer briefs and denim in the decade prior, but by the early 1990s the designer had begun to champion a more austere aesthetic, supplanting the bookish coquetry of Brooke Shields with the slouching Kate Moss attired in loose-fitting monochromes. He sought out the British architect John Pawson, best known for imbuing posh vacation homes and airport lounges with hard edges and earth tones, to erect a monument to the second coming of American minimalism—this time not as sculpture, but as sportswear. In the summer of 1994, Pawson and Klein made a pilgrimage to Marfa, Texas, the Judd mecca; Pawson’s wife at the time managed the artist’s furniture sales in London. Klein ultimately decided to use Judd furniture for seating and display in the flagship.

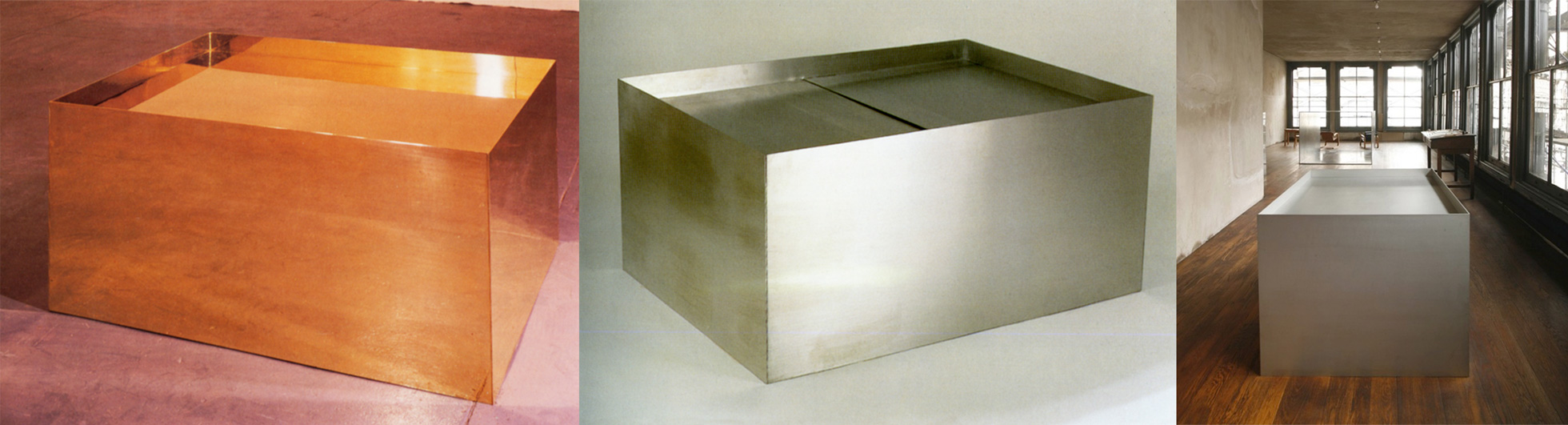

Judd designed his first piece of furniture, a stainless steel coffee table derived from one of his metal sculptures, in 1970. Both objects are stark, rectangular volumes capped with recessed planes. The main difference may be that you can only place your drink atop one of them without offending your host.

To some, Judd’s table confirms the suspicion that his sculptures were never so different from furniture. To others, the table allegorizes the complicated reception of minimalist sculpture—which is also to say the vogue for minimalist design—in the following decades. Since the mid-90s, the relationship between Judd’s work and those who consume, adopt, and claim his style as their own has been marked by strategic affiliations and disaffiliations on both sides. This history manifests the permeability—and ambiguity—of the distinction between original and copy in art and design, and the interests at play each time that distinction is defended or transgressed. How is the right context for an object determined, and how might its meaning shift as a result?

Judd eventually came to deride his first table as a debasement of the original artwork. In his writing, he asserted a quasi-ontological difference between furniture and sculpture; each needed to be approached on its own terms, and one should never serve as the point of departure for the other. Judd disdained “old good ideas made shiny and new” and “‘designer’ Italian furniture,” which was symptomatic of the homogenizing pull of mass production; he claimed it was worse than anything except “the plastic bottles for liquid soap.” Unlike Judd’s artworks, his furniture is now produced in unlimited runs and available for purchase at a fixed price. The artist mandated that his artwork and furniture never be exhibited together, and that his plywood chairs not assume the preciousness likely to be associated with his plywood sculptures; chairs were, emphatically, to be used.

The artist’s furniture yielded little revenue during his lifetime. Judd poured all his resources into the development of his loft on Spring Street in Manhattan, his sprawling Marfa compound, and a lakeside property in Switzerland. These monuments to Judd’s vision belie the financial precariousness precipitated by their execution: The artist died with more than six million dollars in debt and two thousand dollars in his bank account, even as his artworks garnered six figures at auction and his furniture designs became trophies in the realms of fashion and design—and, inevitably, prime targets for replicators. Does the ubiquity of Judd’s work—or of objects made in its image—undermine, extend, or simply confuse his legacy as an artist? Madeleine Hoffmann, who until recently oversaw the furniture division of the Judd Foundation, which looks after the artist’s residences and archives in Marfa and SoHo, was dismayed to hear that one prospective buyer of Judd chairs planned to hang them on the wall. “It’s just furniture, and we sell it just like furniture,” she must often insist. “It’s not art.”

2.

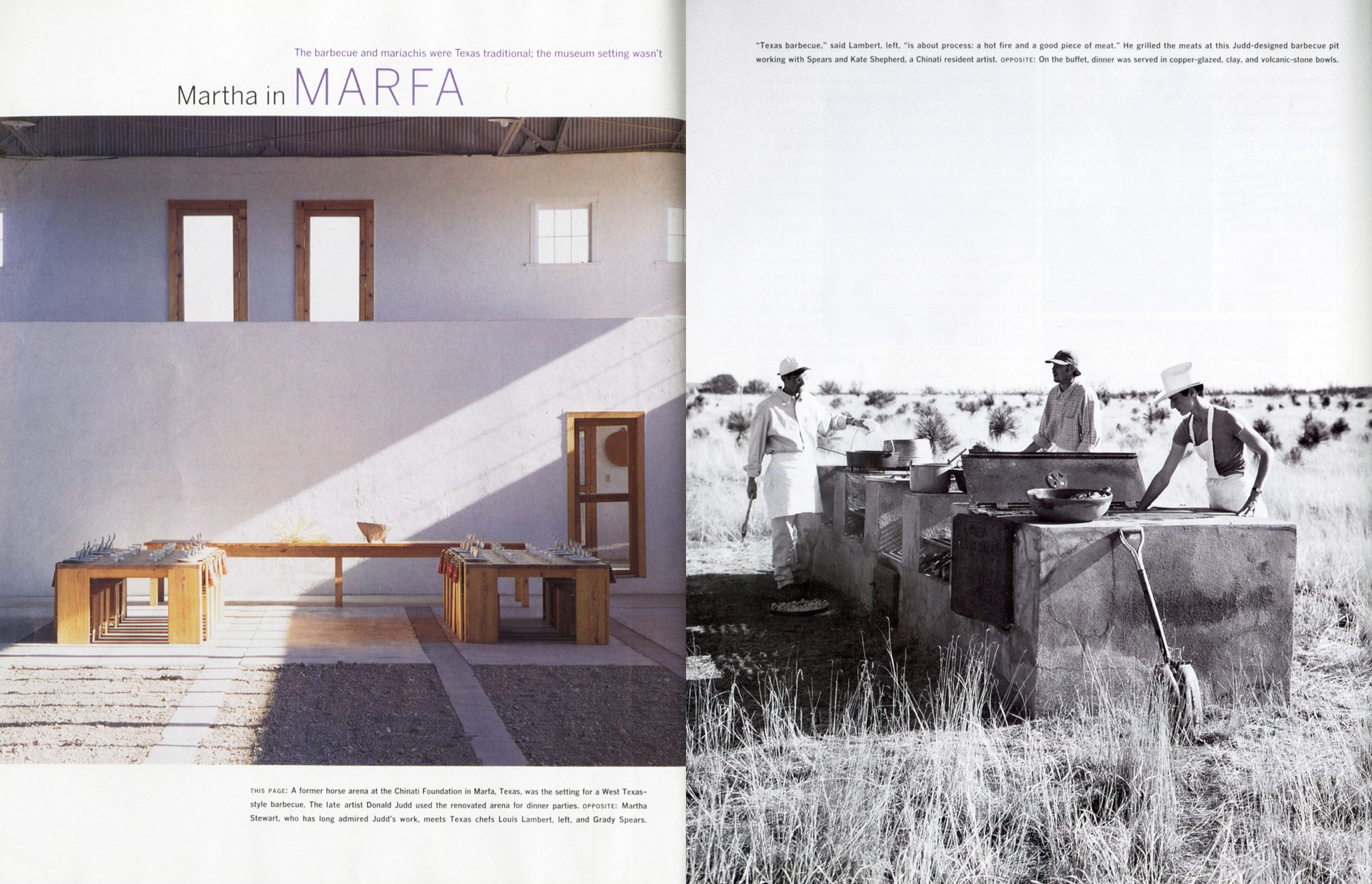

The Judd Foundation worked with Pawson to populate the interior of the Calvin Klein flagship with about twenty pieces of furniture. “We were very involved,” recalls Hoffmann. That said, the relationship was transactional: “They placed an order and we filled it.” Hoffman hoped that Calvin Klein customers would be spurred to purchase Judd furniture, as sales contribute to the nonprofit foundation’s bottom line. Indeed, coverage of the flagship’s opening often corroborated the designer’s minimal aesthetic with mention of the Judd goods. The fever for Judd furniture—and the apparent brand synergy—reached a zenith in the fall of 1995, when an eight-page foldout advertisement launching Calvin Klein Home, and shot against the backdrop of Marfa’s Chinati Foundation, appeared in fashion and lifestyle magazines. The first page featured pillows and gauzy sheets casually draped across a reproduction of a Judd bed frame made for the shoot. Behind the bed hung a painting by Korean artist Hyong-Keun Yunan (part of the foundation’s permanent collection), its dark tones precisely coordinated with the raw concrete floor. The next year, Martha Stewart Living published “Martha in Marfa,” a chronicle of a southwestern barbecue prepared at the Chinati Foundation on a monumental concrete grill designed by Judd and echoing the obstinate sculptures strewn about the surrounding landscape.

The Judd Foundation has a strict rule against hosting commercial shoots, but the independent Chinati Foundation—based in Marfa and initially backed by New York’s Dia Foundation as a venue for the presentation of work by Judd, Dan Flavin, and John Chamberlain—has no such policy and made its exhibition space available to Calvin Klein in exchange for a corporate membership. These photo shoots may have seemed unsavory to Judd adherents, though Chinati deliberately did not use Judd’s sculptures as props. “We didn’t want to mix it,” Marianne Stockebrand, then director of the Chinati Foundation, told the New York Times. “His art should not be decoration for a furniture campaign.” (Incidentally, home furnishings purveyor RH, formerly Restoration Hardware, has adopted a similar position under inverse circumstances: Artworks available through its new RH Contemporary Art division do not appear alongside RH furniture in campaigns and catalogues, nor is its Chelsea gallery space outfitted with RH furniture. “Look, art clearly goes in people’s homes,” CEO Gary Friedman conceded to T Magazine, “but great art can stand alone, and shouldn’t be confused with decoration.”)

Of course, images and objects gain different kinds of value from different kinds of photographic reproduction, which may appear in a Calvin Klein Home advertisement, Interior Design, Artforum, an auction brochure, Vogue, October, or Martha Stewart Living. Putting an object in its proper context, whether a furniture catalogue or an interior design magazine spread or a museum period room, is supposed to help it signify correctly. But how many collectors fill their homes with, for instance, nineteenth-century folk art and colonial-era furniture, constructivist canvases and Bauhaus chairs? And what of objects with ambiguous status or ancestry, which may not fit easily into the categories of fine art or craft or design, which are anyway far from stable? Why shouldn’t I hang a Judd chair from the wall of my apartment?

The fear, occasionally bordering on paranoia, of artworks being perceived as decorative has long haunted prominent strands of modernism. “I find myself in the realm of good design,” sneered critic Clement Greenberg in a spirited dismissal of minimalist sculpture in the late 1960s. (As art historian James Meyer points out, “Good Design” was the name of a series of design exhibitions at MoMA in the 1940s and ’50s that aspired to “encourage tasteful consumption.”) Art has, of course, often been called on to play a supporting role in fashion and lifestyle magazines. A 1951 Vogue spread featured ethereal ball gowns whose colors matched backdrops of Pollock drip paintings; art historian T. J. Clark calls this the “bad dream of modernism,” suggesting that the glossy pages “bring to mind—or stir up in us against our will—the most depressing of all suspicions we might have about modernism as a whole.”

3.

The realms of modern art and design have never really been separable. Judd, for his part, believed that his artworks were best seen in “permanent installations” alongside furniture and decorative objects in his residence in Marfa and at 101 Spring Street. The Wadsworth Atheneum’s 1964 exhibition “Black, White, and Grey,” featuring Frank Stella, Robert Morris, and Tony Smith, served as the backdrop for a Vogue spread that placed high fashion and high art cheek by jowl. A few years later Judd and Ellsworth Kelly were employed to model clothes in Harper’s Bazaar. “Primary Structures,” the landmark 1966 exhibition at the Jewish Museum, was one of the first dedicated to minimalist sculpture, but was also remarkable for the debut, at the opening, of the so-called Primary Structures dress. More recently, Vogue lauded “minimalism: the dress”—the most judicious style choice of 1995—and counseled readers on “how to wear minimalism”: “Keep it spare and simple. Believe less is more. Think in black and white. Maximize the minimal.” From the start, minimalism doubled as a lifestyle.

“Calvin has always liked a Minimalist approach to art,” the vice president of Calvin Klein Home said, simply, at the time of the Chinati Foundation campaign. The Chinati Foundation spaces made for appealing backdrops because they were “spare and light” and “made the products stand out.” The VP went on to note that many of Klein’s designs were inspired by Judd’s. Some borrow obliquely from his formal vocabulary of hard-edged quadrilaterals, unadorned materials, and permutational open cubes; others are mirror-image copies or scaled reproductions.

Equally, if not more, brazen knockoffs abound. Pawson has made furniture that pays homage to Judd; around the time of the opening of the Calvin Klein flagship, architect Roberto Baciocchi created display fixtures for a Miu Miu boutique that were explicitly modeled after late Judd sculptures. IKEA’s LACK floating shelf is hardly distinguishable from a unit in one of Judd’s vertical stack sculptures, especially when viewed online as a minuscule JPEG. (See the quiz “Donald Judd or Cheap Furniture?”: I twice received a humbling score of 92%, which suggests that, at least online, there are only simulacra.)

Judd’s ethos of extreme reduction makes his furniture emblematic of the difficulty of copyrighting a chair or table: Functional objects cannot be copyrighted unless their aesthetic aspects can be “conceptually separated” from their utilitarian properties. In effect, this means that the only copyrightable elements of a useful object are those that appear to be tacked on to the basic form—a ballerina figurine on the base of a lamp, a swath of ivy adorning a wrought iron chair—and thus could plausibly be removed without the object failing to function. However, intellectual property law does protect utilitarian objects that were initially conceived as aesthetic works and only later took on a functional application. For example, the Ribbon Bike Rack was deemed copyrightable because its creator claimed that the form had initially been conceived as a sculpture. Judd’s first coffee table, being derived from a sculpture, arguably meets the same criterion. But, of course, Judd renounced any relationship between his art and furniture. “Furniture and art can only be approached as such,” he wrote in 1986. “Art cannot be imposed upon them.” Ironically, the features that distinguish Judd’s furniture (extreme formal reduction, omission of decorative elements, evacuation of the superfluous), coupled with his disavowal of any relationship to his sculpture, have made the furniture impossible to copyright.

Today, anyone can make a 3-D scan of a Judd chair with her phone and upload the resulting CAD to Thingiverse; anyone can commission a 3-D printed or plywood replica of a Judd stool via an online marketplace. Given the convergence of object, image, and data, copyright law and traditional conceptions of ownership and originality seem increasingly obsolete. The question isn’t whether something is a knock-off or an original, but what it signifies and to whom. Since 1872, the Met has allowed copyists to set up in the museum and create authorized reproductions of artworks in situ—provided that sculptures don’t exceed one cubic foot, canvases aren’t larger than thirty by thirty inches, and the size of the copy differs from the original by at least ten percent. (Copyists aren’t permitted to work on commission or to sell their works in the museum.) In the past few years, institutions such as the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Getty, the Met, and the Rijksmuseum have made high-res, reproduction-quality images of works that are in their collections and in the public domain freely available online. However, the same institutions—or perhaps only their gift shops—might cringe at the notion of visitors making unauthorized scans and replicas of Brancusi sculptures or antique washbasin stands.

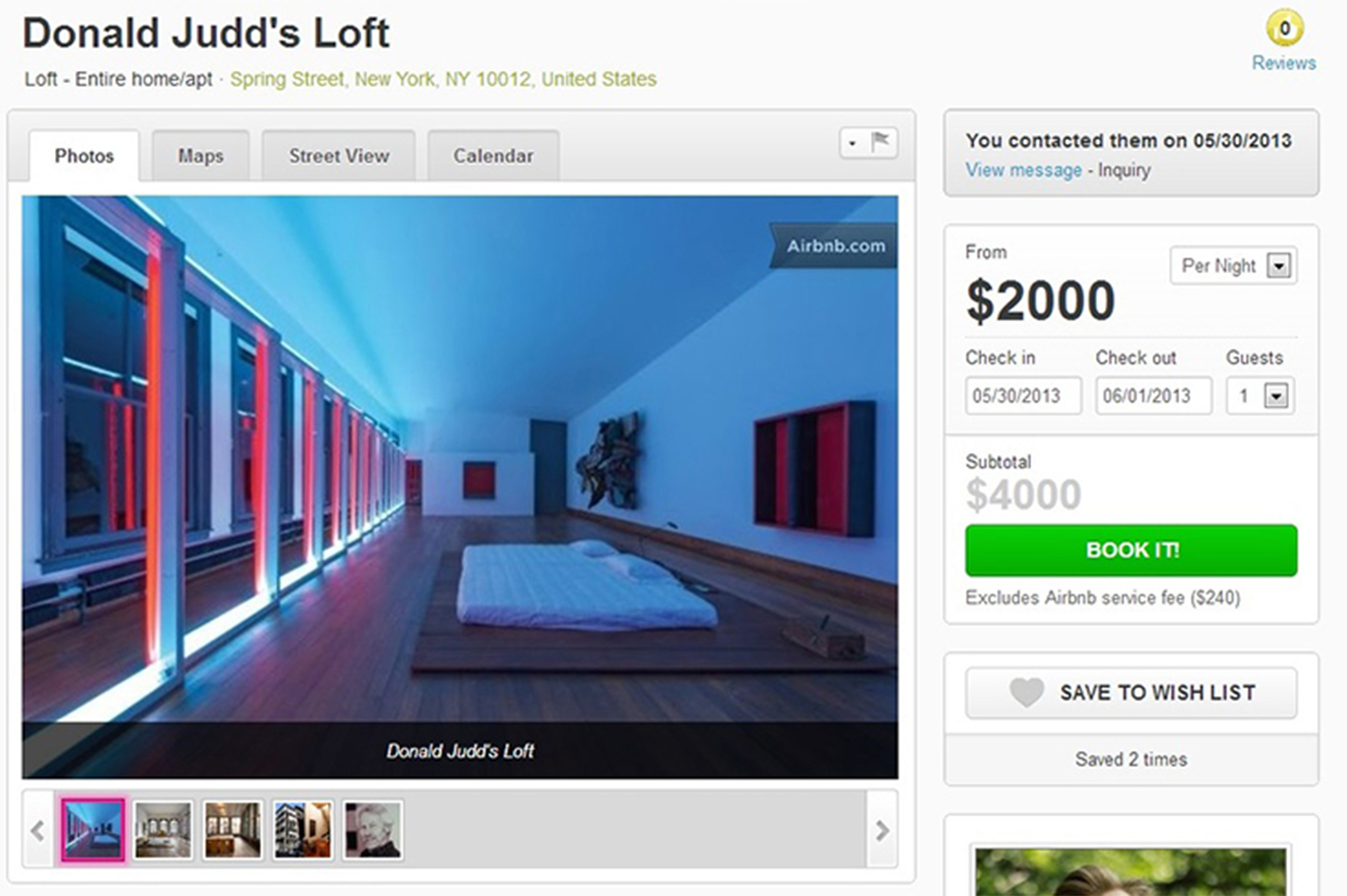

If visibility is itself currency, the reproduction and circulation of images and objects may ultimately enhance their value. (Recent studies suggest that counterfeit items actually benefit luxury brands because they enhance their profile and desirability.) Take, for example, Judd’s Spring Street loft, which has been perfectly preserved since before his death, each enamel spoon and Staedtler pencil transformed into a component of the tableaux. Snapshots of similarly precious domestic arrangements are now ubiquitous online, making these configurations seem strangely contemporary. Two summers ago, a spoof listing for “Donald Judd’s Loft” appeared briefly on Airbnb; it hardly felt hyperbolic. “The way people are living is very Judd,” the artist’s dealer, David Zwirner, recently told the Independent. The statement cuts both ways. The extent to which an artist’s oeuvre resonates in museums as well as in everyday life is, in a certain sense, the ultimate testament to its influence. By that measure, Judd is doubtlessly one of the most important artists of his generation. Museums and nonprofit organizations that derive income from the authorized production, reproduction, and circulation of objects indelibly imprinted with the names of authors and artists have, understandably, been slow to embrace this attitude.

Pollock iPhone cases and Monet silk scarves aside, an understanding of authorship borrowed from folk art might, anachronistically, be most applicable to digital culture. The imperative to clearly attribute a work to an individual is particular to our era and its dominant economic forces: It arose in Europe and the US only in the eighteenth century, amidst the rampant piracy of texts and inventions, when ideas came to be classified as personal property. In contrast, folk art has long been characterized by practices of borrowing, merging, reworking, and metabolizing generic and popular motifs with little concern for citation. Walter Benjamin remarked that folk art “passes certain themes from hand to hand, like batons, behind the back of what is known as great art.” Folk art reflects collective desires and needs, and is most often tailored to the idiosyncratic purposes of the creator or of a niche community. In practical and legal terms, contemporary reproduction technologies make it impossible to stanch the flow of images and objects; as soon as they enter into circulation, their status becomes unstable. The dwindling numbers of those who fervently erect dams or plug leaks tend to have a financial or intellectual stake in the enfeebled system.

Minimalist sculpture, and the work of Judd in particular, was premised on the refutation of the idea that art primarily expresses individual inspiration or interiority. Judd’s projects in Marfa and at Spring Street sought to collapse the distinction between high art and everyday life by integrating spaces for work, study, exhibition, and domestic life; the diffusion and derivation of Judd’s impassive forms in the realms of fashion and design seem only fitting. For its part, the Judd Foundation is mostly unconcerned by all the replicas. As Hoffman told me, those who want the “real thing” will still seek it out. For this portion of the population, to recognize the gulf between Donald Judd and cheap furniture is a matter of taste; the knockoffs can only enhance the value of the original. For the rest of us, there’s always Zazzle.