The Visit

We receive a text message from an unknown number— inviting us to “visit the present.” At first we wonder if we are being disparaged, since we consider ourselves very much of the moment. Puzzled, we weigh various interpretations. What are the characteristics of the present age? This isn’t simply a matter of listing smartphones, IPCC assessments, definitive personae, and hallmark conflicts, but of establishing a fundamental idea of an epoch. We begin to feel ridiculous, curse the invitation, yet also feel—who knows why—compelled. We accept. Anyway, we’ve lately spent too much time feeding words to machines (an activity that was to figure prominently on our list).

We are directed to the gleaming lobby of a Manhattan office complex. We watch workers—young and old, dressed for AutoCAD and Filemaker—swipe their cards and caress their phones; they seem to have organized themselves, organized the world, into a reliable repertoire of manual gestures. We are reminded of a story written in 1850 by Edgar Allan Poe, “The Sphinx.” Two gentlemen flee New York City during an outbreak of cholera to hole up in a cottage on the Hudson. Very little happens, until the narrator looks out the window one morning and sees a “living monster of hideous conformation”— covered with black fur, a massive crystal horn protruding from its head, a white skull outlined on its chest—charging toward him. The narrator loses consciousness. On waking he is informed that he was only looking at a moth, “the genus Sphinx,” that had become trapped in a spider’s web.

This is what it is like when distance collapses. There is a terror in the dandy’s reduced field of vision that we, sequestered in a noiselessly ascending elevator, seem to share: Everything is near, and nothing that is not near can be perceived.

A Show

We enter an auditorium. It’s a relief to settle into cushioned folding chairs, to have the lights dim. We recall that in Poe’s time the telegraph promised, or threatened to annihilate the interval between sender and receiver, to level the differences between original and copy, convert the book into code. That age—characterized by the inscrutable speed and complexity of financial exchange, the circulation of texts copied and cobbled together by both heedless and purposeful printers (for profit, for the public sphere), a crisis of authorship, the First Transcontinental Railroad—recalls our own. Does this alleviate our anxiety, this ability to recognize in the past an approximation of the present? Now as then, we can say that the original accrues value while the copy creates value. But can we say that we are free, democratically so, to do what we like within the narrowing distance between goods and information about these goods?

The screen before us flashes to life:

A Slide

We see ourselves in a twentieth-century American museum. We hesitate beneath suspended concrete-grid ceilings and can’t help but dwell on the sluggishness of the sculptures and paintings. There is a reason, beyond the immaculate architecture, climate control, and careful displays that we are pleased to be at the museum. We are sympathetic to the modeling of images, objects, ideas, and experiences that occurs here, to the ceaseless accumulation of records, to the tensions that ensue. On the one hand: the promotion and repetition of orderly stratification, division, and classification, the consolidation of value in unique objects. On the other: the replication of artworks via photography, facsimile, press release, catalogue entry, forgery, or conversion into code, all of which may distort or diminish the singularity of the original, even while granting it a special status. We wonder how we might marshal such opposing forces as we attempt to reproduce and, in some sense, possess these artworks—whether in print or online or as 3-D scans converted into CAD files to be widely distributed, modified, and materialized. We consider and compare possible strategies and formats for representation, conversion, and translation, as we can expect varying degrees of information loss, addition, or modulation.

A Slide About Language

We see a page of a novel, but not the original page, nor a scan of a credible edition on Google Books, but rather an e-book with text reformatted to accommodate proliferating mobile devices. An animation of the page turning on screen. An animation of the page turning on screen. An animation of the page turning on screen. Expressive language, speech; the alphabet (we are English speakers) with its familiar associated phonemes, “Bababadalgharaghtakamminarronn konnbronntonnerronntuonnthunntrovarrhounawnskawntoohoohoordenenthurnuk,” as a peal of thunder introduces the postlapsarian world in Finnegan’s Wake. We have for some time been trying to figure out how we can write and speak alongside, or against, the highly accurate and undeniably impressive forms of presence rooted in digital scripts and interfaces. We have fixated on anachronism.

A Slide About Legacy

We see a contemporary factory floor dominated by neat plastic enclosures: 3-D printers being tested and boxed, shipped to medical research facilities, Department of Defense contractors, wealthy hobbyists. Technicians in white lab coats, whom we regard with a mix of awe and contempt, perform adjustments; they are skilled, advanced, and potentially rendering millions obsolete. All the same, there is an undeniable fascination in the applications of this technology, and we ourselves have recently been marveling at the plan of the Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities to create a perfect replica of Tutankhamun’s tomb. A company called Factum Arte (“dedicated to … the production of works that redefine the relationship between two and three dimensions”) is measuring 100 million points within each square meter of the pharaoh’s final resting place, employing laser scanners to convert the texture and colors into code. The resulting copy will provide visitors a more complete, touchable encounter. Practically no one will ever have to enter the tomb again—until the copy begins to deteriorate and the original must be scanned again, though perhaps simply reproducing the first copy is preferable; each preserves something of value.

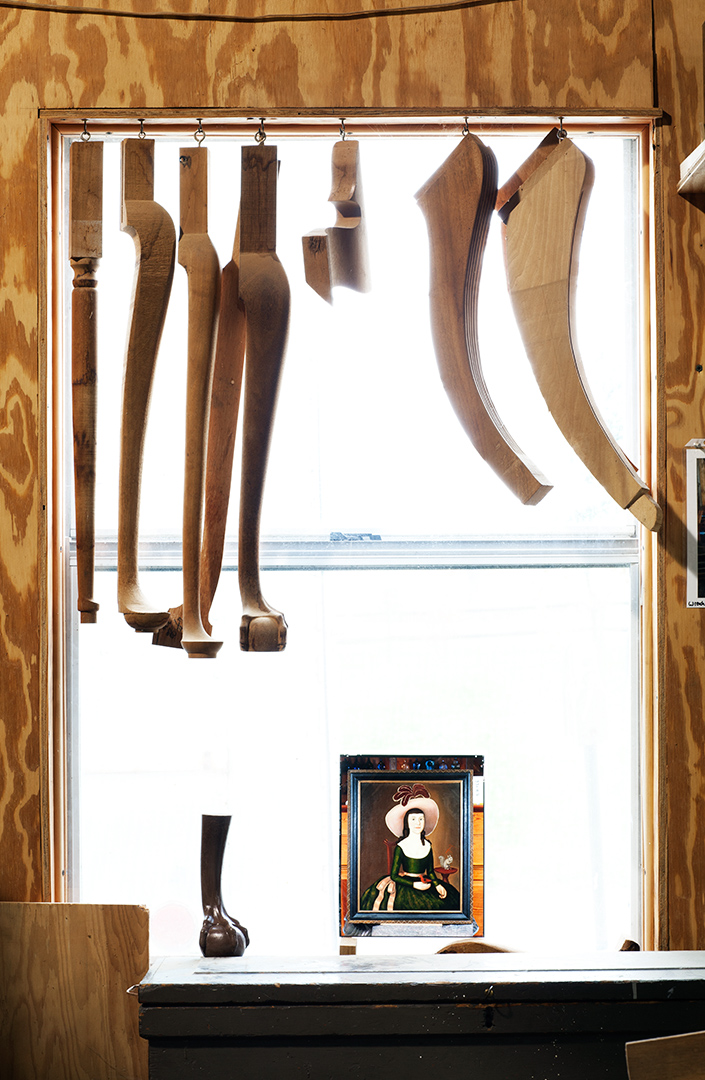

A Slide About Historical Painting

We see ourselves again, this time in a private home that also seems to be another museum. In the image we are seated as we are now, except in Queen Anne walnut side chairs, in proximity to cabrioleleg zomnos, lacquered escritoires, and one extraordinary fruitwood bench. There are so many paintings of George Washington. Washington in snow-white breeches with blooming cheeks, Washington claiming dominion over peaked cherry trees, Washington dangling gilded symbols of the Masonic order from his waistcoat. All are seemingly made from the same template, yet none are derivative. Now we see ourselves online, conducting image-based searches for these paintings, for Calder style mobiles, best Saarinen knockoffs, Jasper Johns upload image Zazzle posters. Ionic molding, roses pompon wallpaper, an anonymous portrait of a lusterless young girl, her torso cinched into a satin bodice. We are reading that copyright originated in the eighteenth-century distinction between copying a book (mindless) and reproducing a machine (edifying). Some believe the pointing machine, which plots the surface of a sculpture so as to facilitate the creation of copies, was developed to service the hunger for Greek statuary among the elites of conquering Rome; others believe that no special apparatus was developed until the Renaissance, when there arose a great demand for reproductions of classical sculpture. “A work of art, since it is an object, may be copied and re-casted,” Immanuel Kant pronounced in 1785, “and the copies thus made of it may be publicly circulated without requiring the consent of the author of the original or of those whom the latter used as the executors of his ideas.” To Kant, the separation of the writer’s identity from the written work—via reprinting, amalgamating, bowdlerizing, anthologizing, appropriating—threatened public reason, and so the pirate must assume authorship.

We are seeing this house-museum recreated as a showroom, as an archive, as an interiordesign layout, as a chart of the divagating paths taken by each object—painting, commodity, decoration, holding, auction item, Ektachrome slide, eBay purchase—and as something we can take with us. We see ourselves step outside, onto the deck, ignite an e-cigarette, and take in the flatness of Maryland.

Plaster

The slide show ends. We are immersed in a convincing approximation of natural light streaming into the atrium of a museum that brims with plaster casts, obviously historical, potentially futuristic. An impassive Apollo Belvedere regards the coiled figure of the Discobolus; the Apoxyomenos scrapes sweat and dust from his skin; Laocoön and sons pry miserably at determined serpents. Crowded together are the Capitoline Venus, Venus de Medici, Venus de Milo, and Michelangelo’s Slaves. Diana Chasseresse selects an arrow as a young stag leaps behind her dimpled knee. Another version of the present, within the present: we reach for our phones in order to capture it and find a new message from the unknown number: “This is how order is made and unmade.”